Posted by Krista Kesselring, 9 July 2017.

Deaths in gaol have long required investigation by coroners. In Canada, one provincial jurisdiction recently sought to end this practice to save time and money, but abandoned the proposal upon protests that the public had a duty and right to oversee custodial conditions.[1] The mandatory inquest into deaths of prisoners has a long history, dating back to the medieval origins of the coroner, when his duties centered on preserving the king’s rights and revenues. Looking at early modern inquests makes one wonder about their purpose and utility, in an era when gaol deaths were rife and the inquests typically perfunctory.

As one might expect, gaol deaths kept early modern coroners and their inquest jurors busy: J.S. Cockburn’s study of the assize court records extant for the five Home Counties between 1559-1625 noted inquests into no fewer than 1,291 deaths in custody, observing too that not all the relevant records survive. (To put this number in context: this same set of records includes indictments for 11,731 people and sentences of death for 2,828.[2])

Looking at some of these inquests a bit more closely indicates that the coroners had less than exacting standards. In the dozens of prison deaths reported to Sussex coroners between 1558-1688 for which records survive, helpfully if grimly calendared by R.F. Hunnisett, jurors deemed three to be intentional suicides: according to their inquests, Joan Whighting strangled herself with the cord from her girdle in Rye’s town gaol in 1572, and both Richard Cheapman and John Johnes hanged themselves with their own clothing in 1602 and 1605 respectively.[3] William Marsh reportedly killed himself accidentally, falling from a great height when trying to escape the Rye gaol.[4] Otherwise, jurors deemed all but one of the many other deaths the products of ‘natural causes’, aka ‘the visitation of God’.

Coroners’ juries deemed the deaths natural even when they came thick and fast in a manner suggesting an outbreak of some sort of infectious disease or particularly insalubrious conditions. In 1578, for example, Horsham gaol hosted six inquests into the deaths of eight men and women between January 6 and February 22.[5] True, some people could survive in these gaols for quite some time: Simon Godfrye, remarkably, survived in Horsham’s gaol for eleven years, first charged in 1588 with recusancy – or failure to attend church – and then repeatedly remanded upon failure to meet the terms needed for release, until his death in gaol in 1599, again of ‘natural causes’.[6] Of a group of five women convicted of burglary in May 1604, one was immediately hanged but the other four remanded to prison, one after successfully demonstrating her pregnancy to secure a temporary reprieve; one we lose track of thereafter, but of the other three, one survived in gaol about a year, dying of ‘natural causes’ in April 1605, another survived almost two years, dying in March 1606, again of ‘natural causes’, and the third – Margaret Squyer, the one who’d been remanded for her pregnancy – lasted a little more than two years, until her hanging on 29 July 1606.[7] The number and nature of these inquests confirm that a remand to gaol to await trial or upon a trial’s end was a fearsome prospect, and yet that deaths in custody were almost invariably thought to be ‘natural’.

In 1586, a few inquests reported upon groups of dead prisoners, in ways suggesting both grim conditions and a laxity to the inquest process. On 20 October 1586, county coroner Magnus Fowle and thirteen jurors held one inquest on five dead prisoners in Horsham gaol; on 20 November, Fowle and the same jurors pronounced their verdict on six more bodies; just two months later, on 23 January 1587, the same group met for another inquest, this time on five victims.[8] Instead of commenting on each death individually, the coroner seems to have been processing batches expeditiously and, unusually, employing (or simply listing) the same jurors repeatedly. That something a bit unusual and improper was happening is also suggested by the parish register, which included a note for 1586-7 that ‘The prisoners that died in the gaole at Horsham this year, and buried in the churchyard, were not made knowen to the Vicar & therefore are not here entred.’[9]

While all these inquest reports noted that the coroner had observed the legal requirement to hold the inquest ‘upon view of the body’, that seems in some cases to have been a lie: a February 1591 inquest at Horsham gaol reported the deaths from natural causes of both John Depprose and John Shepe, ostensibly held upon view of both bodies, yet the local parish register indicates that a ‘John Shepe, prisoner’ had been buried weeks earlier.[10] Perhaps questions had arisen (or maybe gaol fever was just too rife), as the next two inquests – in May 1591 on three dead prisoners and in July 1591 on three more – took place in the churchyard rather than in the gaol itself.[11] Before long, though, one finds more inquests dated days after a burial is recorded in the parish register. John Howell, for example, was buried on 13 December 1613, though an inquest ostensibly ‘on view of the body’ was dated five days later.[12]

Only very, very rarely does one find an inquest report suggesting that the conditions of custody or actions of gaolers had something to do with the deaths. In these same Sussex records, one — unfortunately so badly damaged as to be frustratingly illegible in places – notes that Edward Bridger had been shot dead by the gaoler when trying to escape, but with text suggesting that the gaoler ought not to be held to blame as Bridger had tried to kill him.[13] In one other I’ve found from another county, jurors attributed the deaths of six prisoners not to ‘natural causes’ but more bluntly to ‘frigore & fame’ – cold and hunger.[14]

These inquests give us some insight into the conditions of early modern imprisonment, but also raise questions about the purpose and efficacy of the process itself. Did the legal provision that coroners had to hold inquests into prison deaths do anything to benefit prisoners? Not much, it would seem; neglect and hard conditions passed with little or no comment in most cases, though it’s possible that the requirement may have restrained the occasional gaoler from violent excesses that would leave marks. While imputations of wrong-doing are almost impossible to find, that some inquests carefully stressed the lack of guilt might indicate that the inquest bore some weight: the inquest into Thomas Fisher’s death in the Rye town gaol, for example, insisted that Fisher had been ‘extreame sick a longe tyme before his imprisonment’ and emphasized that he had died simply ‘by the handy worke and visitation of God’ alone.[15] In another, into the death of a 28-year old carpenter imprisoned for debt, jurors specifically asked that their verdict that the man had died a natural death of ‘hectic fever’ be formally entered and enrolled among the records of the coroner and mayor.[16] Would one bother with making such excuses and formalities if the inquest had no weight at all?

In a few cases, inquests on deaths in custody more clearly served a public interest, or at least prompted interest from the public, with an afterlife in print. The death of Richard Hunne in 1514, while incarcerated on a charge of heresy, was one of the first and most famous of such cases. The London coroner Thomas Barnwell and his jury of twenty-four men deemed Hunne’s death the result of murder by his gaolers, not suicide. Though intervention from the king ensured that the accused did not face justice, the publication of details about the inquest at the time – and their reiteration in John Foxe’s history of the Protestant Reformation and its martyrs – ensured this jury a place among the heroes of the Reformation, a group of men who stood bravely for truth when faced with ‘devilish malice’. [17]

Years later a different set of religious conflicts framed a public dispute over another prison death and the inquest upon it. James Parnell, the ‘boy Quaker’, died in the Colchester gaol in 1656, aged about nineteen, after being imprisoned when he couldn’t pay the fine imposed for his disturbance of a church service. The inquest jury decided that he had caused his own death by fasting and voluntarily sleeping on the cold stones, a verdict quickly used to malign his fellow Quakers as fanatics. In contrast, his defenders argued in print that the lingering effects of a fall he’d suffered when trying to get into the hole high in the wall assigned as his cell had likely led to his death, or that the beatings he received from the gaoler’s wife and various other cruelties imposed upon him had done so. One described a rushed inquest, though one that sounds less perfunctory than the hasty jobs at Horsham: the coroner did call before him a couple of witnesses who had recently spoken with Parnell, inquiring about both his fast and the fall, but called no more when some of the jurors insisted that they needed to get home and asked to hasten the verdict.[18]

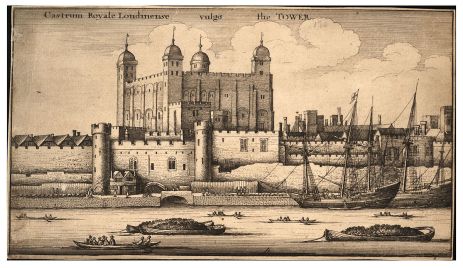

High status and high political intrigue could also prompt interest in a prison death and the resulting inquest. When Henry Percy, eighth earl of Northumberland, was found dead in the Tower in 1585, authorities had a pamphlet published with details about the inquest to try to assure the public that the earl had killed himself.[19] When another earl died in custody almost a hundred years later – Arthur Capel, first earl of Essex, arrested for his part in the Rye House Plot of 1683 and found in the Tower with this throat slit – authorities had a harder time controlling the public narrative, with competing publications dissecting the inquest’s proceedings and countering its verdict of suicide with evidence for murder.[20]

Reading through the reports on these inquests, one starts to think of them not so much as investigations providing a modicum of oversight but as veils to obscure the violence of early modern imprisonment, appearing to provide accountability but in fact doing little of the sort. The occasional contestation of an inquest’s verdict, though, suggests that they didn’t just routinely fail in the first function but also, sometimes, in the second.

Images: The woodcut depicting Richard Hunne’s death from John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments, via George Townsend’s 1837 edition, from the Flikr Commons.

The Tower, by Wenceslaus Hollar, courtesy the University of Toronto’s Wenceslaus Hollar Digital Collection.

[1] See, e.g., http://leaderpost.com/news/saskatchewan/death-knell-sounds-for-mandatory-in-custody-inquests

[2] J.S. Cockburn, Calendar of Assize Records: Home Circuit Indictments, Elizabeth I and James I: Introduction (London: HSMO, 1985), pp. 36, 39, 125, 145-71.

[3] R.F. Hunnisett, Sussex Coroners’ Inquests, 1558-1603 (Kew, PRO Publications, 1996), nos. 103, 573; R.F. Hunnsett, Sussex Coroners’ Inquests, 1603-1688 (Kew, PRO Publications, 1998), no. 34.

[4] Hunnisett, Sussex 1603-1688, no. 238.

[5] Hunnisett, Sussex 1558-1603, nos. 194-99.

[6] Hunnisett, Sussex 1558-1603, no. 530.

[7] Hunnisett, Sussex 1603-1688, nos. 30, 47. See The Parish Register of Horsham in the County of Sussex, 1541-1635, ed. R. Garraway Rice (Sussex Record Society, v. 21, 1915), p. 366.

[8] Hunnisett, Sussex 1558-1603, nos. 334, 335, 340.

[9] Rice, Parish Register, p. xxiv.

[10] Hunnisett, Sussex 1558-1603, nos. 334, 335, 340, 410; Rice, Parish Register, p. 350.

[11] Hunnisett, Sussex 1558-1603, nos. 414, 416.

[12] See, e.g., Hunnisett, Sussex 1603-1688, nos. 119, 139, 143, 250; Rice, Parish Register, p. 379.

[13] Hunnisett, Sussex 1603-1688, no. 386.

[14] The National Archives: Public Record Office, KB 9/567, m. 171.

[15] Hunnisett, Sussex 1603-1688, no. 147.

[16] Hunnisett, Sussex 1603-1688, no. 499.

[17] The Enquirie and Verdite of the Quest Panneld of the Death of Richard Hune (Antwerp, 1537?).

[17] See Foxe, Acts and Monuments, book 7, pp. 969-78.

[18] Anon., The Lambs Defence Against Lyes, and a true testimony given concerning the sufferings and death of James Parnell (London, 1656).

[19] Anon., A True and Summarie Reporte of the Declaration of some Part of the Earle of Northumberlands treasons delivered publicly in the Court at the Starrechamber…by her Maiesties special commandement…touching the maner of his most wicked & violent murder committed upon himselfe (1585).

[20] See, e.g., Murder will out, or a clear and full discovery that the Earl of Essex did not murder himself, but was murdered by others (1684), Michael MacDonald, ‘The Strange Death of the Earl of Essex, 1683’, History Today 41 (1991), 13-18 and Melinda Zook, Radical Whigs and Conspiratorial Politics in Late Stuart England (University Park, Pennsylvania, 1999), pp. 116-19.

The issues to which Professor Kesselring has drawn attention in this excellent paper did not end in the sixteenth century. The office of the coroner, like the institution of the jury, is one of these entities that has survived since medieval times but has undergone considerable metamorphosis in the process. Perhaps like other aspects of English society, the office of coroner may have continued to exist without any great thought being given to its functions and purposes.

It is perhaps trite to observe that when coroners first began to investigate deaths there was no police force, and one aspect of the early coroner’s office might well have been the limited factual enquiry into an immediate cause of death which today would be achieved by a police surgeon or a forensic pathologist.

Modern coronial practice is governed by statute, but the statutes were enacted against the common law background which Professor Kesselring describes. Typically, coroners are required to ascertain, where possible, the identity of the deceased, and to state “how, when and where the deceased came by his death”: see for example s 11(5)(b)(ii) of the Coroners Act 1988 (UK). A series of decisions including R v HM Coroner for Birmingham, Ex p Secretary of State for the Home Department (1990) 155 JP 107, R v HM Coroner for Western District of East Sussex, Ex p Homberg (1994) 158 JP 357 and R v HM Coroner for North Humberside and Scunthorpe; Ex parte Jamieson [1995] QB 1 established that the word “how” meant “by what means” and not “in what broad circumstances”. This narrow construction of the expression “how … the deceased came by his death” limited the relevant finding to the manner of death – such as strangulation caused by a ligature – and did not permit any excursion into the broader questions surrounding the death – for example, of why people might have hanged themselves, or whether their deaths could have been prevented. In R (Sacker) v West Yorkshire Coroner [2004] UKHL 11; [2004] 1 WLR 796 and R (Middleton) v West Somerset Coroner [2004] UKHL 10; [2004] 2 WLR 800, both deceased had hanged themselves while in prison. Prison suicide was (and remains) a serious issue, and the 1999 Ramsbotham Report had revealed that the prison suicide rate more than doubled between 1982 and 1998. Despite these concerns, the narrow approach endorsed by Ex parte Jamieson persuaded the coroners in Sacker and Middleton not to allow juries to include in their verdicts a view about the negligence of the prison authorities. The appeals in those cases were allowed by the House of Lords, but only because of the effect of article 2 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, incorporated into UK domestic law by the Human Rights Act 1998. The Convention, which relevantly provides that “everyone’s right to life shall be protected by law”, requires that the coroner be given a broader jurisdiction to enquire into the circumstances surrounding the death.

LikeLike

I very much enjoyed your post, but wondered about the jury composition for gaol inquests. I am only familiar with 18th century London practise, but all gaol inquests I have seen for Middlesex and the City require a jury to be composed of half prisoners and half householders – see for instance: https://www.londonlives.org/browse.jsp?div=LMCOIC65101IC651010010. Is this a new thing in the 18th? It has always seemed to me to be a very odd practise that speaks loudly to the distinctive nature of early modern and 18th c. prisons. The number of prison inquests held for Middlesex [via the coroners’ bills] also feel to me to be quite high – https://www.londonlives.org/browse.jsp?div=LMCOIC65101IC651010001. How serious they were is open to debate, and most of the ones I have read (as you suggest) put deaths down to ‘natural causes’. But, the Westminster series in particular – which include all the related informations – suggests that substantial evidence was collected https://www.londonlives.org/browse.jsp?div=WACWIC65225IC652250152. Of course, this series does not include instances where an indictment was issued – but with the jury composition suggests that prison conditions were accepted as supportable by both prisoners and coroners. There are also some nice prison cases in the Old Bailey, that suggest that inquests occasionally resulted in indictments, and which tend to revolve around violence directed at prisoners by figures of authority. One of my favourites is: https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/browse.jsp?id=t17840915-66-off327&div=t17840915-66.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much for this. I’ve not seen anything in the 16th and early 17th century inquests I’ve looked at to suggest that the juries consisted partly of prisoners. I’ll definitely keep an eye out for this in future. Figuring out when this began, and why/how, would be fascinating.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve noticed by chance (happened to have names pop out at me as I flipped through files of coroners’ inquests in the 1530s) that at least some of the jurors for prison deaths in the Marshalsea were themselves prisoners. I just went back and looked at my photos of the originals, and in at least one run of several such inquests (KB 9/975, mm 235-38), it was made explicit that half the jurors were prisoners. The other half were called “viator[es]” — which normally means “travellers” or “wayfarers,” so that’s a bit mysterious. If I were to make a guess, I’d say that the use of prisoners as jurors in prison death inquests was likely a practice that went back well before the 1530s, but I haven’t followed that up. As I commented to Krista earlier in an email, it is particularly interesting given how we’ve normally thought about jury service as indicative of local standing and as participating in state building.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tim, this is fascinating. I had not known that prisoners routinely sat on coroner’s juries in the 18th century. But I just posted on Early Modern Prisons about prisoner’s complaining in the 1720s that they were not included in the coroner’s jury. Which of course suggests that they expected to be. I’d love to know when it became normal to include them.

LikeLike

I’m really curious now to get back to the archives to see if any sixteenth or early seventeenth-century inquests can be found that indicate the residence of the jurors. In the meantime, playing around with what’s easily available, a quick search on EEBO turns up The Case of Sir John Lenthall, Knight, Marshall of the Upper Bench Prison (1653), in which Lenthall defends himself from one of many charges of misdoing with a note that the inquest into the 1640 death of one of his charges, George Smithson, was held before a jury consisting of six prisoners and six neighbours (p.9). Umfreville cites 14th-century precedents for the mixed jury in his 1761 Lex Coronatoria (p. 213). [He also recounts a more recent instance in which the six prisoners did not agree with the ‘six foreigners, who were of opinion the death was fair and in a natural way, but the six prisoners were of opinion he died of grief, because the Marshal would not take such fees as the deceased was willing to pay; and the Court would not receive the judgement of the six prisoners, in regard the fees were ‘extra’ their inquiry, and it was impossible for them to know that he died of grief, which is an inward affection of the mind’. The six prisoners were fined and discharged from the inquiry, and another six prisoners brought in who agreed with the ‘foreigners’.]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] also had a direct physical and psychological impact on their inmates. As Krista Kesselring’s new post explains, many people died in prison through disease or starvation, and others experienced it as an anteroom […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Early Modern Prisons and commented:

We are delighted to share this post by Krista Kesselring, Professor of History at Dalhousie University. It originally appeared on the Legal History Miscellany blog on July 9, 2017.

LikeLike

[…] on early modern coroner’s inquests into prisoner deaths, which originally appeared on the blog Legal History Miscellany. I have never looked systematically into the records of coroner’s juries, as Professor Kesselring […]

LikeLike