By Cassie Watson; posted 13 September 2017.

The recent spate of acid attacks in London has led to renewed political and media attention on an especially horrific form of assault designed to maim and humiliate by damaging or even destroying the victim’s face with corrosive fluid. Criminologists and the police have been quick to note the links to youth gangs who would otherwise use knives to carry out assaults,[1] and this perhaps helps to explain the high proportion of male victims in the UK in comparison to other countries where the crime is prevalent. According to Acid Survivors Trust International, acid attacks tend to affect women and girls disproportionately, reflecting patriarchal assumptions and gender inequality; it is believed that many attacks are not even reported for fear of reprisals.[2] Although some journalists have noted that this crime is not new,[3] it is clear that its characteristics have changed. Acid attacks were a regular if not common occurrence in nineteenth-century Britain; but while they were, as today, a largely urban phenomenon, they were not associated with street gangs or even with criminals. Otherwise law-abiding adults of both sexes threw acid for reasons that were often surprisingly sympathetic: betrayed and abandoned, or aggrieved and powerless, people lashed out when they felt they had no other option. So who were the Victorian acid throwers and why did they do it?

A Woman’s Crime?

In February 1882 an editorial in The Times commented on what was then known as vitriol throwing, after oil of vitriol, strong sulphuric acid: “In the class from which the actors in this ghastly drama are drawn ‘spite’ is a powerful engine, which acts in a ruder and less refined manner than it acts in the higher circles of society. [In this class] furens femina operates with violence and vitriol, with open scandal, or even with the weapons of a murderer. In a higher sphere her vengeance is more thought out, more subtle, though not, perhaps, less agonizing or less effectual”.[4]

This neatly summarises the assumptions that middle-class Victorian males held about acid throwers: they were “furious women”, working class and irrational, acting from motives of jealousy and revenge. This stereotype was well entrenched by the 1880s, and was played out numerous times in the dramas, short stories and novels of the last quarter of the century.[5] It survived well in to the twentieth century, too: in 1936 a textbook of forensic medicine stated that chemical burns “may be caused by attempts by jealous women to disfigure their rivals, as in vitriol-throwing”.[6]

However, it was not just a woman’s crime. Of the over 400 cases that I have studied, the perpetrators were evenly divided between male (191) and female (189); 5% of cases involved group assaults perpetrated mostly by men.[7] Acid throwing was used as a means of dispute resolution, but the disputes were mostly personal and men were just as likely to lash out as women were.

Types of Acid Attacks

Acid attacks that resulted in death were rare: in Scotland, where the crime was made a capital offence in 1825, a married couple were prosecuted for attempted murder in 1827 after the victim died from complications,[8] and in London in 1881 a young woman was acquitted of the mysterious murder of a man in a public house.[9] In 1894, it was said, the secretary of the Danish Legation in London died the day after vitriol was thrown over him in a robbery.[10] In fact, murder was never the intended aim of the vitriol thrower: some simply wanted to destroy clothing; others stated firmly that they’d intended to blind their victim. Almost without exception, vitriol was thrown at the head, neck and upper body, sometimes directly in to the face; the ubiquitous wearing of hats often prevented the worst damage.

Aiming for the victim’s face suggests a deeply personal motive on the part of the attacker, although robbers tended to do this in order to incapacitate their victims. But there was a bizarre form of vitriol throwing in which complete strangers squirted or threw acid on ladies’ dresses, usually sneaking up from behind and then running away. This clearly deviant behaviour mystified contemporaries, but was probably committed by men suffering from some sexual or emotional dysfunction.[11] Attacks always occurred in clusters, usually in London or other large cities, and the attackers were rarely caught. The earliest report of such an assault dates from 1785, and there were further outbreaks in England at least seven times during the next eighty years. Similar crimes occurred frequently in the United States, where in 1854 one persistent attacker was finally apprehended. Theodore Gray, dubbed ‘Vitriol Man’ by the New York press, had attacked dozens of women with acid squirted from a contraption hidden in his pockets or sleeves. He denied that he was insane but could not say why he committed such acts, although he admitted that financial problems were a contributory factor.[12]

Acid throwing during industrial disputes occurred during the first half of the century in England, Scotland and Ireland, and usually involved mobs of men (and sometimes women) squirting or throwing vitriol over looms, fabric or machinery. More seriously, mill owners were sometimes attacked and disfigured: in Ireland in 1842 four sawyers were transported for life for blinding a man who had just built a steam-powered saw mill.[13] Such incidents were no doubt fresh in reader’s memories when Elizabeth Gaskell included an incident of vitriol throwing in her novel Mary Barton (1848), which addressed the antagonism between masters and workers in Manchester.[14]

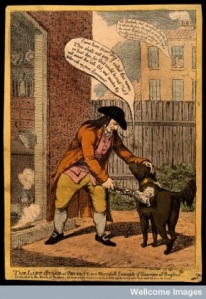

Even animals fell prey to acid throwing, when perpetrators sought to strike an indirect blow at the owners. One notorious incident in 1806 resulted in a heated civil trial: the plaintiff was represented by the famous William Garrow; defence counsel admitted the offence but cautioned against punishing the defendant (a Quaker chemist) by awarding damages beyond the cost of the dog. But the Lord Chief Justice was clearly outraged and awarded damages of £5, stating his expectation that the Society of Friends would expel the defendant, John Glaisyer, for “such unparalleled cruelty”.[15]

Even animals fell prey to acid throwing, when perpetrators sought to strike an indirect blow at the owners. One notorious incident in 1806 resulted in a heated civil trial: the plaintiff was represented by the famous William Garrow; defence counsel admitted the offence but cautioned against punishing the defendant (a Quaker chemist) by awarding damages beyond the cost of the dog. But the Lord Chief Justice was clearly outraged and awarded damages of £5, stating his expectation that the Society of Friends would expel the defendant, John Glaisyer, for “such unparalleled cruelty”.[15]

Legal Responses

The law was for many years unequal to the seriousness of the offence, and although it could be prosecuted under statutes against damage and wounding, the penalties were light. Early cases show that when clothing was destroyed, the crime was tried as damage to property, resulting in a small fine or short gaol sentence. Its effects on the person were not adequately provided for until the 1820s when the use of vitriol in disputes between masters and workmen in Glasgow led Parliament to extend the English Stabbing and Wounding Act to Scotland, making vitriol throwing a capital offence.[16] In England, by 1840 vitriol throwing with intent to damage clothing or do grievous bodily harm had become a form of felonious assault subject to prison or transportation, and a law of 1847 raised the maximum penalty to transportation for life, but there were loopholes concerning the definition of a wound. Finally, the Offences Against the Person Act of 1861 made it a felony to burn, maim or disfigure anyone with a corrosive fluid.[17] A legal loophole remained, however: no offence was committed if there was no intent to injure. Some alleged perpetrators claimed they had accidentally spilt acid – a defence that occasionally succeeded despite the amount of planning this crime required.[18]

Yet surprisingly, jurors could often be remarkably sympathetic to perpetrators. In many cases juries convicted but made a recommendation to mercy. Judges usually accepted these and gave light sentences of a few months or years in prison, sometimes with hard labour. The harshest penalties, prison terms of 10 years or more, were reserved for those who could not claim to have acted under provocation. This included revenge for matters unrelated to a broken relationship, and those who had a history of violence. Most of the longest sentences were imposed on men. There seems to have been a tacit acceptance that acid throwing could amount to a crime of passion and that a person provoked to violence by the hurtful actions of a loved one, especially a lover or spouse, should not be treated as harshly as others, especially if they expressed remorse. As one magistrate remarked in 1847, “when seduction was the beginning, mischief was almost sure to overtake the seducer in the end”.[19]

Victims

Victims of vitriol throwing could suffer serious physical, emotional and economic consequences: the acid could cause blindness and severe mutilation. In 1823 a Scottish surgeon noted that he had seen ears drop off in one piece.[20] If the injuries were extensive victims could be permanently disabled; those who recovered were likely to be badly disfigured. What became of them once their burns had healed? As is often the case when researching the history of crime, we have little information about how the people involved fared once their court cases had ended. However, in the 1860s a public appeal revealed the fate of one male victim.

In November 1865 a young Londoner named Felix Deacon was friendly with a married woman, Sarah Ann Peacock, for whom a dentist named Wainwright had developed a passion, leading to so much jealousy that he threw vitriol in Deacon’s face, blinding him completely. Wainwright was not identified until he attacked Mrs Peacock in January, for which he was sentenced to 20 years in prison.[21] Deacon, who had been a skilled lithographer, had to go into the St. Pancras workhouse, as his family could not maintain him. A teacher employed by the Home Teaching Society for the Blind taught him to read Braille, but he remained in the workhouse for four years, unable to learn any trade that a blind man could follow. In 1869 the honorary secretary of the Society published a letter about Deacon in The Times, asking for the public’s assistance. Within two weeks nearly £50 had been pledged, enough to send him to an institute where he would be taught how to use a knitting machine, in the expectation that he would then be able to earn a living.[22]

A window into the emotional turmoil that a vitriol attack could cause is opened by the brief notice of the death of a young man in Nottinghamshire. The body of Albert Alonzo Drummore, an actor, was pulled from a river in July 1888 and an inquest heard evidence which suggested that he had taken his own life. A former schoolmaster aged 26, he had recently taken up acting but had been blinded in one eye when acid was thrown into his face during a rehearsal in Sheffield. He lodged a civil suit for damages, but lost.[23] It is thought the injustice preyed on his mind and drove him to suicide.

Conclusion

Vitriol throwing continued until the Second World War, thereafter becoming much less frequent. The Pharmacy and Poisons Act of 1933 restricted the sale of strong sulphuric acid, so that weaker corrosive fluids were used; and as fewer cases were reported, the tendency to copycat behaviour lessened. By 1955 a toxicologist writing in the British Medical Journal described vitriol throwing as a “rare and execrable crime”,[24] and records held at the National Archives indicate that sulphuric acid was rarely used in post-war incidents. The upsurge in reported cases over the past decade is therefore noticeable and troubling, but history shows both that the crime is rooted in socio-cultural norms and that it can be tackled effectively.

Images:

Main image: Eugène Grasset, La Vitrioleuse (c. 1894) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

John Glaisyer a Quaker anointing a dog with burning vitriol oil; implying a satirical attack on the Quaker movement. Coloured etching by C. Williams, 1806. Image courtesy of Wellcome Library, London, catalogue record 12200i.

Mary Morrison (50), convicted at Lancaster Assizes July 1883 and sentenced to 5 years penal servitude. The victim was her husband Christopher. She was released on licence in 1886. The National Archives, Kew, PCOM 4/65/24 (reproduced by permission; image not to be copied).

References:

[1] Vitriolic, BBC Radio 4, 6 Sept 2017, http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b092m4s8 (accessed 6 Sept 2017).

[2] http://www.acidviolence.org/a-worldwide-problem.html (accessed 8 Sept 2017).

[3] Julia Rampen, “As bad as stealing bacon – why did the Victorians treat acid attacks so leniently?”, 27 July 2017, http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/uk/2017/07/bad-stealing-bacon-why-did-victorians-treat-acid-attacks-so-leniently (accessed 8 Sept 2017).

[4] The Times, 21 Feb 1882, 10c.

[5] See for example Sabine Baring Gould, Mehalah: A Story of the Salt Marshes (1880), chapters 24 and 25; George Gissing, The Nether World (1889), chapter 23; Arthur Conan Doyle, ‘The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle’ (1892) and ‘The Illustrious Client’ (1924).

[6] Douglas Kerr, Forensic Medicine, 2nd edn (London: A. & C. Black, 1936), 110.

[7] These figures cover the period 1795-1975. A listing of some American cases since 1865 focuses on female perpetrators.

[8] Katherine D. Watson, “Is a burn a wound? Vitriol-throwing in medico-legal context, 1800-1900”, in I. Goold and C. Kelly (eds), Lawyers’ Medicine: The Legislature, the Courts and Medical Practice, 1760-2000 (Oxford: Hart Publishing, 2009), 72-73.

[9] The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, 1674-1913, www.oldbaileyonline.org, trial of Marie McIlvey, ref. t18810627-620.

[10] R. A. Witthaus, Manual of Toxicology, 2nd edn (New York: William Wood and Company, 1911), 255. I can find no English press accounts of this incident.

[11] Consider the links to picarism, stabbing in which the knife represents the penis. Or, the destruction of rich fabrics may be an expression of class hatred. See Richard von Krafft-Ebing, Psychopathia Sexualis, with especial reference to Antipathic Sexual Instinct: A Medico-Forensic Study, 10th edn, trans. F. J. Rebman (London: Rebman Ltd, 1899), 105, 255.

[12] The Times, 8 Dec 1854, 6e; 12 Dec 1854, 7b.

[13] The Times, 9 Aug 1842, 5d.

[14] E. Gaskell, Mary Barton, pbk edn (Oxford, 1998), chapter 16.

[15] The Times, 6 Aug 1806, 3.

[16] Robert Christison, A Treatise on Poisons (Edinburgh: A. Black, 1829), 115.

[17] Watson, “Is a burn a wound?”, 73-78.

[18] Katherine D. Watson, “Love, vengeance and vitriol: an Edwardian true-crime drama”, in A-M. Kilday and D. Nash (eds), Law, Crime and Deviance since 1700: Micro-Studies in the History of Crime (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), 111.

[19] The Times, 1 Dec 1847, 7e.

[20] National Archives of Scotland, AD14/23/73, case of Alexander McKay and others (Glasgow, 1823); testimony of Dr James Corkindale.

[21] The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, 1674-1913, www.oldbaileyonline.org, trial of John Wainwright, ref. t18660409-378.

[22] The Times, 28 Jan 1869, 5e; 15 Feb 1869, 10d.

[23] The Scotsman, 31 July 1888, 3.

[24] J.D.P. Graham, ‘Emergencies in General Practice: Corrosive Poisoning’, British Medical Journal, 16 April 1955, 962-964 (on p.962).

Only today I was curious about the high incidence of ‘vitriol throwing’ in Victorian crime fiction and happened upon your fascinating and timely article.

LikeLike

I would love to know more about the wider incidence of vitriol throwing in Victorian fiction / drama – has there been any research on this published?

LikeLike

[…] Acid Attacks in Nineteenth-Century Britain – Legal History […]

LikeLike

[…] Acid Attacks in Nineteenth-Century Britain, By Cassie Watson; 13 Sep 2017. […]

LikeLike