Posted by Sara M. Butler; 19 February 2018.

Should animals be seen as persons under the law? At first glance this question may seem preposterous, but many animal rights activists today see that recognizing animals as “non-human persons” is the logical next step. Peter Singer, professor of bioethics at Princeton University and co-founder of the Great Ape Project, explains that extending basic human rights to animals is the only way to protect them from human exploitation and cruelty.[1] Currently, animals fall under the category of property in Anglo-American law, which prevents them from suing for better treatment (or, obviously, a guardian suing on their behalf). Recognizing them as “non-human” persons would offer an easy remedy to an untenable situation. Moreover, given our contemporary knowledge of animal behavior, there are few grounds to sustain an argument for human exceptionalism. Animals share many traits previously thought to separate human from other species: reason, language, emotion. It would seem that animals have “earned” the right to be considered people. The inspiration for this strategy came from law in practice. In 2015, a judge awarded writs of habeas corpus to two lab chimps at Stony Brook University, an error that was quickly amended, but not before animal rights activists had come to appreciate how such a creative misunderstanding might benefit the legal defense of animals.[2] For the Canadians among our readership, working with the malleability of the definition of “person” is a familiar tactic in the history of human rights, remembering a time not that long ago when the category of person was so narrowly defined it did not even include women.

How have we reached a point in our society where awarding animals the status of non-human persons makes sense both legally and culturally? In The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence has Declined, Steven Pinker sees this approach as distinctly modern, a predictable outgrowth of the civil rights ideology. He contends that the “revolution in animal rights” that has taken place since the 1980s is “uniquely emblematic” of the growing empathy that has come to characterize the modern era, and is also the stimulus for continually declining levels of violence.[3] But is this empathy new, or are we, in fact, returning to a medieval outlook on animals?

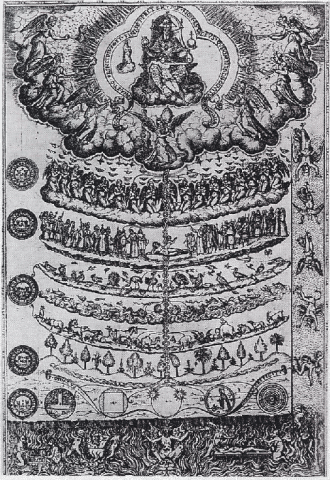

In environmental circles, blame has been heaped on the medieval church for fashioning and perpetuating the ideology of human dominion. So the argument goes medieval theologians interpreted Genesis to mean that God created plants and animals for “man’s benefit and rule: no item in the physical creation had any purpose save to serve man’s purpose.”[4] Yet, a survey of animal philosophy, as well as human-animals relations in medieval Europe suggests quite the opposite. The Christian  worldview, trumpeted from pulpits and captured gracefully in paintings, acted as a constant reminder that humans, animals, and nature are all integral parts of God’s creation. The Great Chain of Being represents the universal hierarchy as a chain extending from the feet of God down to nothingness, with human beings sandwiched nicely between angels and animals. Such an integrated view of creation stresses the co-dependency of each class, as well as their shared attributes. With angels, humans share the ability to reason, and their spirituality; yet, the animated bodies of both humans and animals tie them inextricably together, and to the earth. This worldview explains much of humanity’s baser behavior: why do some people “eat like pigs,” “breed like rabbits,” engage in “cat fights,” or act like “jackasses”? These are moments when the human capacity for reason is clouded, causing an individual to slip from one category to another.

worldview, trumpeted from pulpits and captured gracefully in paintings, acted as a constant reminder that humans, animals, and nature are all integral parts of God’s creation. The Great Chain of Being represents the universal hierarchy as a chain extending from the feet of God down to nothingness, with human beings sandwiched nicely between angels and animals. Such an integrated view of creation stresses the co-dependency of each class, as well as their shared attributes. With angels, humans share the ability to reason, and their spirituality; yet, the animated bodies of both humans and animals tie them inextricably together, and to the earth. This worldview explains much of humanity’s baser behavior: why do some people “eat like pigs,” “breed like rabbits,” engage in “cat fights,” or act like “jackasses”? These are moments when the human capacity for reason is clouded, causing an individual to slip from one category to another.

The potential for slippage is inscribed in law as far back as Bracton (thirteenth century), in his discussion of the legal accountability of the mentally disabled:

Because they lack sense and reason and can no more do wrong or commit a felony than a brute animal. Since they are not far [from being] brutes, according to what can be seen in the minor, if he kills someone while under age, he will not suffer judgement.[5]

While humans sometimes behave as animals, from the medieval perspective, it was just as likely for animals to behave as humans. Indeed, animals were sometimes better Christians than were humans. Haven’t you heard of the paralyzed mule, “cured because of its faith”? When Mary graced the good mule with a miracle freeing it from illness, the blessed animal went directly to the church of the Virgin, circled it three times, then entered and bent its knees in prayer before the high altar.[6] How about the bees who built a shrine out of honeycomb to house the Lord’s body in the form of the Eucharist?[7] And who can forget Saint Guinefort, the sainted greyhound who patronized sick children?

While these exempla help us to understand how average men and women might accept movement between categories on the Great Chain of Being, medieval scholastics were also in on the game. They expended much parchment on the debate over whether animals had souls. Even if Saints Augustine and Thomas Aquinas emphatically rejected the possibility, their opinion was not unanimous and various saintly visions in fact undermined their confident statements. Saint Perpetua’s revelation of heaven as agricultural bliss, where God dresses as a shepherd milking the sheep, would certainly seem to imply there’s a place in heaven for animals. An eleventh century mosaic from the cathedral at Torcello (Italy) showing animals and fish resurrected (and “vomiting up the human body parts they had eaten in their lives” in the process) indicate that some ecclesiastical officials believed animals even participated in the Great Resurrection.[8] All of these examples confirm that the line between humans and animals was blurry at best in the medieval imagination.

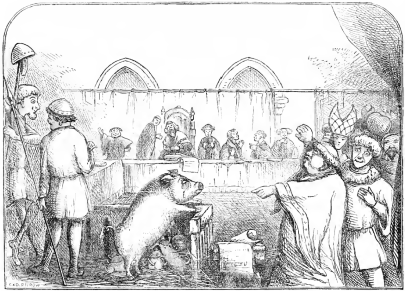

Medieval law also saw the anthropomorphosis of animals. In both ecclesiastical and secular courts from the thirteenth century well beyond the Middle Ages, courts across Continental Europe, as well as Scandinavia, Canada, and Brazil, conducted animal trials, in which animals  effectively were awarded the status of non-human persons.[9] Vicious dogs, murderous pigs, and randy mares – all appeared before the court as defendants, tried according to the laws and procedures typically reserved for humans. Some were convicted, and hanged or excommunicated accordingly. Others were acquitted, and their names returned to pristine fame. Barthélemy de Chasseneuz (1480-1542), a jurist who wrote a treatise justifying animal trials, made a name for himself as an advocate with the creative defense of a mischief of rats, accused of eating the barley crops of a group of farmers in Autun. When the rats failed to respond to multiple recitations of a court summons, read aloud in those areas where the rats were known to frequent, delivered also in written form and posted on churches in all the neighboring towns, Chasseneuz pleaded his clients’ fear of cats, dogs and hostile people, openly haunting the streets en route to the courthouse and making the journey one of great peril for his clients![10]

effectively were awarded the status of non-human persons.[9] Vicious dogs, murderous pigs, and randy mares – all appeared before the court as defendants, tried according to the laws and procedures typically reserved for humans. Some were convicted, and hanged or excommunicated accordingly. Others were acquitted, and their names returned to pristine fame. Barthélemy de Chasseneuz (1480-1542), a jurist who wrote a treatise justifying animal trials, made a name for himself as an advocate with the creative defense of a mischief of rats, accused of eating the barley crops of a group of farmers in Autun. When the rats failed to respond to multiple recitations of a court summons, read aloud in those areas where the rats were known to frequent, delivered also in written form and posted on churches in all the neighboring towns, Chasseneuz pleaded his clients’ fear of cats, dogs and hostile people, openly haunting the streets en route to the courthouse and making the journey one of great peril for his clients![10]

It is easy to argue that animal trials were expedient. Medieval men and women turned to the law because it was a preexisting solution for a problem that they were incapable of resolving otherwise. If the court passed against the rats, didn’t they have an obligation to enforce their sentences? But Chasseneuz’s Consilia (1531) hints that that might be too simplistic an analysis. He argues in favor of seeing animals as persons, specifically because they know the difference between right and wrong. He claims that “animals knew when they transgressed because they tried to conceal their deeds and exhibited fear or timidity when their miscreance was discovered.”[11]

Here, the medieval English stand out as an exception. They did not conduct animal trials. Rather, the dog who mauled a child to death was treated as deodand in a case of misadventure. Deodand is an object forfeit to the king because a coroner’s inquest found it had caused a person’s death. The category included not only animals, but also tree branches that fractured under the weight of a child, causing him to plummet to his death; wells where individuals drowned or suffocated; runaway wagons responsible for running people down, etc. The word deodand means “to be given to God,” thus it should come as no surprise that the value of the objects were given to the king, and used to fund a charitable cause. As this process implies, animals in England belonged to the category of objects. Admittedly, though, the animals were rarely surrendered to the king: instead their value was, and it is not hard to imagine that many would have been resistant to the very notion of relinquishing their animals. A miracle story from the canonization trial of Thomas de Cantilupe recounts how Robert and Leticia Russell actually hid their own son’s body rather than have it discovered and risk having their oxen confiscated for misadventure![12]

In other instances, English law wavered between treating animals as objects or as persons. The law treated stealing a person (ravishment, or abduction) differently than stealing an animal (theft, robbery, or larceny). Killing a person was homicide, a felony, but killing an animal a mere trespass. When it comes to medical malpractice, however, we once again see great similarities between the two. Compare:

Henry Thorne of South Petherton, chaplain, was attached to answer John Russell of Shepton concerning a plea why, whereas the same Henry undertook at Lopen well and competently to restore to health the left shin-bone of the same John which had been accidentally injured, the aforesaid Henry so improvidently and negligently applied his cure to the aforesaid shinbone that the shinbone became so stiff and weak that he could not go about with the aforesaid shinbone or support himself, to the damage of the same John of twenty pounds, etc…[13]

with

John de Elsham, chaplain, comes in his proper person to answer Robert Lascels of London, marshal, concerning a plea why, whereas Robert undertook at London for a competent salary to cure and keep a certain infirm horse of John’s, the said Robert so improvidently and maliciously applied his cure to the aforesaid horse that the said horse, worth 10 marks, died on account of his default and other enormities, etc.[14]

These lawsuits look eerily similar, in part because the medieval world engaged in a “one medicine” model, in which animals were treated medically with the same methods as were humans.[15] Thus, not only were horses subjected to dietary adjustments, grounded in humoral theory, but The Boke of Marchalsi, a late medieval English reference book for farriers, explains that horses also need to have their blood let as they are prone to an excess.[16] Briony Aitchison remarks that we cannot know whether this was merely advice proffered, or if farriers actually carried it out.[17] But trespass litigation includes a number of cases of horse phlebotomy gone awry. Alan Botiler sued John Ferour of Chipping Sodbury in 1374 because in order to cure an infirmity in his horse’s shins, John “indiscreetly cut the veins of the abovesaid horse’s shins and so negligently applied his cure on the abovesaid horse that the abovesaid horse of a price of £10 died.”[18] The same year, Stephen White also sued William Turry, farrier, for cutting “a certain nerve in the left hind foot of Stephen’s horse in bleeding the abovesaid horse” at Lugwardine, which regrettably led to the rotting of the horse’s foot, and its eventual death.[19]

These cases of medical malpractice are another example of how similarly the medieval world treated humans and animals. It is hard to deny that the two categories were much closer then than they are today. The idea of treating animals as “non-human persons” would not have been seen as ludicrous in the medieval context. Should this be our model?

Images

Main Image: Illustration from a North French Hebrew Miscellany manuscript [Public Domain] via Wikimedia Commons.

1579 Drawing of the Great Chain of Being from Didascus Valades, Rhetorica Christiana [Public Domain] via Wikimedia Commons.

Trial of a Sow and Pigs at Lavegny, The Book of Days: A Miscellany of Popular Antiquities [Public Domain] via Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Nicholás Mandeau, “Should Animals have ‘Human’ Rights?” Deutsche Well (July 29, 2016), http://www.dw.com/en/should-animals-have-human-rights/a-19427091. Accessed 14 February 2018.

[2] Sean Davidson, “Non-human persons? Animal Rights get Legal Leg Up,” CBC News / World (May 26, 2015), http://www.cbc.ca/news/world/non-human-persons-animal-rights-get-legal-leg-up-1.3058148. Accessed 14 February 2018.

[3] Steven Pinker, The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence has Declined (New York, 2011), 456.

[4] Lynn White, Jr. “The Historical Roots of our Ecologic Crisis,” Science, n.s. 155.3767 (1967), 1205.

[5] Italics are mine. Henri de Bracton, De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliae, ed. George Woodbine, ed. and trans. Samuel E. Thorne, 4 vols (Selden Society, 1968-1976), II, 424.

[6] From “The Cantigas de Santa Maria of Alfonso X (c. 1250-80),” cited in John Shinners, ed., Medieval Popular Religion 1000-1500: A Reader, 2nd edition (Toronto, 2008), 136-37.

[7] From “Caesarius of Heisterbach’s Miracles of the Eucharist (c. 1220-35),” cited in Shinners, 106-7.

[8] Joyce E. Salisbury, “Do Animals go to Heaven? Medieval Philosophers Contemplate Heavenly Human Exceptionalism,” Athens Journal of Humanities & Arts 1.1 (2014), 82.

[9] Esther Cohen, “Law, Folklore and Animal Lore,” Past and Present 110 (1986), 13.

[10] Cohen, “Law, Folklore and Animal Lore,” 14.

[11] Thomas A. Fudgé, Medieval Religion and its Anxieties (New York, 2016), 21.

[12] For further discussion of this case, see Sara M. Butler, Forensic Medicine and Death Investigation in Medieval England (New York and London, 2015), 49.

[13] The National Archives (TNA), Kew, Surrey: C[ommon] P[leas] 40/503, m. 224 (1386), as translated in Morris S. Arnold, Select Cases of Trespass from the King’s Courts 1307-1399, 2 vols (Selden Society, 1985-1987), II, 427.

[14] TNA: CP 40/440, m. 260 (1369).

[15] Louise Hill Curth, ‘A plaine and easie way to remedie a horse’: Equine Medicine in Early Modern England (Leiden, 2013).

[16] As cited in Briony Louise Aitchison, ‘For to knowen here sicknese and to do the leche craft there fore’: Animal Ailments and their Treatment in Late-Mediaeval England (PhD Diss., University of St Andrews, 2009), 115.

[17] Aitchison, 116.

[18] TNA: CP 40/453, m. 444.

[19] TNA: CP 40/455, m. 145d. Robert C. Palmer mentions this case in his English Law in the Age of the Black Death, 1348-1381: A Transformation of Governance and Law (Chapel Hill, 1993), 347.

[…] in animals that has supposedly existed from time out of mind. As Sara Butler suggested in a previous post, perhaps earlier views were more varied and variable than is sometimes now […]

LikeLike