Posted by Krista J. Kesselring, 27 April 2022.

Marriage, Separation, and Divorce in England, 1500-1700, a book that Tim Stretton and I wrote together, is now available in the UK and should be released more broadly soon. It examines why England alone, of all Protestant jurisdictions, did not institute full divorce of a sort that allowed remarriage in the wake of the Reformation. It argues that part of the answer lay in another peculiarity of English law: its exceptionally restrictive notion of coverture, the laws that denied women full personhood and control of property after marriage. The book also explores what people in unhappy marriages did in the absence of divorces that dissolved the marital bond. Church courts offered some people legal though limited separations; turning to secular court records, we found abundant evidence of women and men also effecting their own informal separations. Private settlements provided a sort of alimony, or maintenance for the wife, usually drawn upon the property the woman herself had brought to the union but which remained in the husband’s control. Our work in the court records revealed many stories of individual men and women trying to loosen the bonds of wedlock in a messy variety of ways. Regular readers of the blog will find a few familiar tales in the book—Elizabeth Bourne and her campaign for a divorce in 1582, the subject of the first post I wrote for this site, appears in it, for example. Many other such stories did not make their way into the book, though, and have not yet appeared here either. So, to mark the book’s publication, this month’s post traces a tale that received only passing mention in the text: that of the two ‘Ladies Powys’.

Anne, the first Lady Powys of this pairing, was the eldest child of Charles Brandon, the boon companion of King Henry VIII who became duke of Suffolk. Anne’s legitimacy later came into question, given what Steven Gunn has described as her father’s own ‘murky and reprehensible marital history’, one that ‘demonstrated an asset-stripping opportunism which even his contemporaries found rather shocking’: Brandon had contracted himself with Anne Browne, a gentlewoman to the queen, but abandoned her for her wealthier, widowed aunt Margaret Mortimer. He later had that marriage annulled on grounds that they were too closely related and returned to Anne. She bore two daughters—Anne and Mary—before dying from complications that arose from the second birth. The duke later went on to marry the king’s widowed sister Mary, enjoying the significant wealth from dower lands she acquired through her first marriage, to the French king; after her death, he married his young ward, Katherine Willoughby, to keep hold of her inheritance.[1] While navigating his own marital exploits, Brandon contracted his eldest daughter to his ward Edward Grey, Baron Powys. The two were married by March 1525.

If it was ever a happy marriage, it wasn’t so for long. Edward was soon complaining of Anne’s adulteries. As full divorce remained impossible, he took what he could get: a church court separation ‘of bed and board’, known as a divorce a mensa et thoro, which let them live apart but otherwise kept the bonds of marriage and coverture intact. In 1537, Anne’s father asked the king’s advisor, Thomas Cromwell, to find a way to have her ‘live after such an honest sort as shall be to your honour and mine’: that was something even Cromwell could not do, but he did arrange for Anne an annuity of £100 from her husband, about a quarter of the assessed annual income of his estates. Paying to support an abandoned wife was one thing; to support an adulterous one seemed to Edward quite another. Two years later, he raided Anne’s lodgings and abducted her lover, a Matthew Rochly [or Rottesley], perhaps hoping to secure evidence that might let him stop the pension, but to no avail. After Cromwell’s fall from grace, Powys appealed to the king’s council for permission to stop payment, noting the ‘open whoredom’ of his ‘late wife’. He tried to strengthen his case with claims that Anne and Randall Hayward, the man with whom she then ‘unchastely abideth’, had tried to kill him—and in some of the worst ways imaginable at the time, with a gun, while on his way to do his duty in parliament, and by infiltrating a ruffian into his household staff. Though the council briefly had Anne and Randall committed to the Fleet while they investigated, they ordered that the annuity continue.[2] Being a duke’s daughter had to count for something; it may also have helped that Lord Powys himself was no saint.

Even as he complained volubly about his wife’s adulteries, Lord Powys had taken up with a widow named Jane Orrell, who would eventually claim to be the rightful Lady Powys. In a will Edward wrote in 1544, before heading to war in France, he left most everything to Jane, the three children they already shared, and the fourth expected. The will also included a generous gift to the Chief Justice of Chester and Flint, made overseer of its complicated and optimistic efforts to provide for Grey’s mistress and their illegitimate children. Grey acknowledged that the children were not ‘lawfully begotten’ but gave them his name and depicted Jane as being effectively his wife. Neither the will nor its later codicil mentioned Anne at all.[3]

The death of Lord Powys in 1551 opened the floodgates for a torrent of lawsuits between and on behalf of his two ‘widows’. Both women promptly remarried: Anne to her long-time lover Randall Hayward and Jane to the Welsh gentleman John Herbert. (And in calling themselves ‘Lady Powys’, both persistently ignored determinations that a woman could not retain a husband’s title if she later married a man of lesser status—she could not transmit the former husband’s status to the new and it would be ‘monstrous’ if she should have a dignity superior to that of her husband and head.[4]) Given the nature of coverture, many of the lawsuits were ostensibly between Randall and John—lurking in the archives as suits between ‘Randall Hayward et uxor and John Herbert et uxor’—but they were fought by two women doggedly disputing dower and the other incidents of an estate due to a man’s widow. Upon marriage, a woman’s property became her husband’s to own or control, but upon his death she could expect a jointure income or a dower of a third of his lands for the rest of her life, along with a portion—usually a third—of any moveable goods he possessed. But with two ‘Ladies Powys’ living, whose claim would hold?

Anne immediately contested Edward’s will. In 1552 the church court issued a sentence that set aside Powys’s attempt to make Jane an executor as well as the legacies for her children, finding Anne the ‘true and legitimate wife’ and Jane to have been merely Powys’s mistress.[5] Anne and her husband may have had a formal separation, but according to this court, the marriage—and thus coverture—had persisted, for good or for ill.

Jane, the other ‘Lady Powys’, was not prepared to let the matter go. In one suit for dower at common law, Anne had won the jury’s favour, but in a second suit, the jurors decided against her—according to Anne, because her late husband’s ‘concubine’ was now married to a man with sufficient power and pull in the locality to sway them. Jane continued to press her claim, saying that to her knowledge, she had been Powys’s lawful wife, as he and Anne had had a separation, ‘by reason of which divorce the matrimony before that time had been…dissolved’. Jane’s words were self-interested, of course, but echoed a common confusion and disagreement about the effects of a separation for adultery in the wake of a Reformation in which many reformers had argued strenuously that such divorces ought to be allowed and ought to allow at least the innocent party to remarry.

Jane followed with a stronger argument for denying dower to Anne (though not in gaining it for herself), saying that Anne had eloped to live in adultery with one lover then another—a wife’s elopement had long been grounds for losing her claims to dower.[6] Jane said she had held back on the evidence of Anne’s behaviour before the first jury, as it was so scandalous it was ‘scant meet to be opened’. Before the second jury, though, she shared full details of Anne’s ‘ungodly and incontinent life’. At that point, Anne turned to Chancery to protest Jane’s ‘crafty and sinister’ efforts to deprive her of her due.[7] She brought witnesses to suggest that her separation from Lord Powys had not been of her choosing—he had set her aside first, she said—and to prove that the two had reconciled for the occasional night or two even after he forced her out.[8]

The disputes over which ‘Lady Powys’ could lay claims upon Edward Grey’s estate continued beyond Anne’s death in 1558. In her will, ‘Anne, Lady Powys’ left her husband Randall anything she ought to have had from her father (still in some dispute, given the confused chronology of her birth and her parents’ marriage) as well as everything due to her from her first husband—lands, titles, or ‘matters of dowry or third parts with the arrearages of the same of my first husband, the late Lord Powys’s lands that by the laws of this realm I am entitled unto, by any manner of means or ways’.[9]

It appears that Randall Hayward did reach a compromise with Jane’s son, the young Edward Grey.[10] But that was not to be the end of it. Two other members of Lord Powys’s extended family—Henry Vernon and Edward Kynaston—soon came forward to claim the right to the barony of Powys and some of Grey’s other properties, fighting each other and also Jane’s son, based on claims that the younger Edward was a bastard.

In the meantime, Jane had produced deeds and documentation of various other efforts by Lord Powys to convey property to her and to their children that might bypass questions about the validity of their union. After the death of her husband John Herbert, ‘Dame Jane, Lady Powys’ continued to make her case in various courts, on her own or with her son. But as one opponent in a case in the Court of Star Chamber unhelpfully explained, she ‘was never married to the said Lord Powys and neither could she be married to him, for that his lawful wife then lived and him overlived’. Her son Edward was ‘a mere bastard in the opinion of all laws as well ecclesiastical as temporal’. For good measure, he also tried suggesting that young Edward wasn’t even the bastard of Lord Powys but of some other man Jane had taken up with. He and others alleged elaborate forgeries in which Jane forced a pen into the hand of the dead Powys to have him sign indentures of sale.[11] In the morass of competing stories, one thing became clear: that neither Jane nor her son could sustain claims based on the legitimacy of her union with Lord Powys. ‘Edward the Bastard’ eventually gave up and sold whatever rights he had to a son of the Earl of Pembroke, who would be able to draw upon his own top-notch connections when continuing to fight the battle. For her part, Jane still signed her correspondence as ‘Jane Powys’ through to her death.[12]

Disputes over the Powys barony lingered for centuries thereafter. So, too, did disputes over the permissibility of divorce. Parliamentary divorces became possible for the select few from roughly 1700; judicial divorces became somewhat more broadly available only from 1857. Authorities religious and secular tried to resolve the post-Reformation confusions about divorce with a set of developments at the beginning of the 1600s: in the midst of a Star Chamber dispute in 1602 that turned on the validity of one of three concurrent marriages, Archbishop Whitgift secured a statement from a gathering of clerics that ‘divorce’ for adultery would not dissolve the marriage bond and allow remarriage. New canons in 1604 required that any separations for adultery be accompanied by statements to that effect. In the same year parliament passed a law that made it a capital felony to have two living spouses. And in a 1604 case later cited as precedent, common law judges agreed that in separations for adultery, just as a husband would retain his wife’s property, so would she retain her dower claim upon the marital estate after his death: the coverture created by the marriage bond persisted.

The anonymous author of the late sixteenth-century Lawes Resolutions of Women’s Rights preserved a verse that had circulated about Anne, which claimed that ‘Frankly of her own accord, [She] left her Husband and her Lord’.[13] Men and women in unhappy marriages evidently could and did leave each other throughout the long centuries before divorce became a legal option. But the complications of trying to dissolve early modern marriages were many and varied; as the two ‘Ladies Powys’ had found, coverture and its implications for a woman’s personhood and property were high on the list.

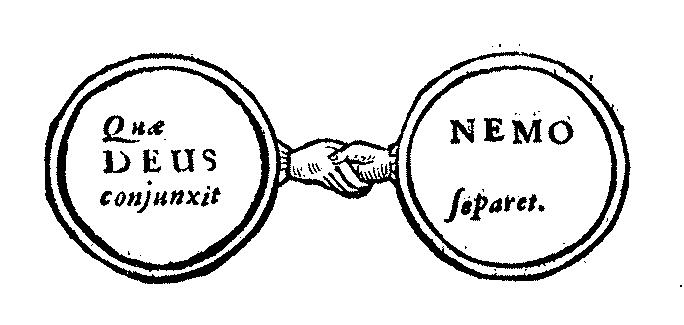

Images:

Feature image: Hans Holbein, Two Views of a Lady, c. 1532-1525, courtesy of The British Museum.

Final image: from Sylvanus Morganus, The Sphere of Gentry, 1661.

Other images via Wikimedia Commons and/or as linked.

Notes:

[1] S.J. Gunn, ‘Brandon, Charles, first duke of Suffolk (c. 1484–1545), magnate, courtier, and soldier’. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004; accessed 15 Apr. 2022 and Gunn, Charles Brandon: Henry VIII’s Closest Friend (Stroud, 2015), 41; for a contemporary recitation of some of these marital misadventures, see The National Archives (Kew) [TNA], SP 1/55, f. 51, a notarial attestation of a bill to ratify Suffolk’s dissolution of the marriage with Margaret Mortimer and C 24/28, for depositions in a suit by Anne that turned on her legitimacy.

[2] TNA, SP 1/121, f. 190 (30 June 1537, Suffolk to Cromwell); SP 1/242, f. 247 (15 June 1538: examinations relating to Lord Powys’s raid on Lady Powys’s lodgings); SP 46/2, f. 124 (Lord Powys’s petition to the Privy Council); APC 3, p. 263 (19 April 1551, council order re: the pension).

[3] TNA, PROB 11/34/203.

[4] See John Ferne, The Blazon of Gentrie (1586), p. 64. Discussed in J.H. Baker, The Oxford History of the Laws of England, vol. 6, p. 619. One of the key cases in fact focused on Anne, ‘Lady Powys’, with a herald opining that if a wife was to use a late husband’s title after marriage to a commoner it was purely as a courtesy.

[5] The sentence is printed in David Jones, ‘Edward Grey, the last Feudal Baron of Powys’, Montgomeryshire Collections 18 (1885), 335-60, quote at p. 357.

[6] For the early modern history of this provision, see especially Gwen Seabourne, ‘Coke, the Statute, Wives, and Lovers: Routes to a Harsher Interpretation of the Statute of Westminster II c. 34 on Dower and Adultery’, Legal Studies 34.1 (2014): 123-42.

[7] TNA, C 1/1434/26-28 and 33-35.

[8] TNA, C 24/32, no. 13.

[9] TNA, PROB 11/40/117.

[10] TNA, C 54/513, m. 30.

[11] TNA, STAC 5/P56/11 (1580/1; quote from Tipton’s deposition). See also STAC 5/P45/7, for more materials from ‘Dame Jane, Lady Powys’; and STAC 5/P2/26, for a case in 1587/8 launched by ‘Henry Vernon, Lord Powys’. Much material from Vernon’s efforts to claim the barony can be found in SP 46/59.

[12] Morris Charles Jones, ‘The Barony of Powys’, Montgomeryshire Collections 2 (1869), viii, quoting a letter said to be dated to 1596, though he also says it refers to John Herbert still being alive, while Star Chamber suits from the 1580s describe him as deceased. See also The Complete Peerage, comp. G.E.C[okayne] (London, 1910-59), v. 10, p. 642.

[13] T.E., The Lawes Resolution of Women’s Rights (London, 1632), p. 145 [published in the early seventeenth century but likely completed late in Elizabeth’s reign]. On the longer history of separations, licit and illicit, see Sara M. Butler, Divorce in Medieval England (London, 2013).

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.