Guest post by Euan Roger and Sebastian Sobecki, 6 July 2023.

The 1873 discovery of a quitclaim [deed of release] by Cecily Chaumpaigne, in which she formally renounced her right to sue Geoffrey Chaucer from any action arising from de raptu meo, fostered the belief that Chaucer may have committed a serious crime. Uncertainty about how exactly to interpret the quitclaim springs from the ambiguity of the term raptus (which translates to “seizure”), used in both rape and ravishment (abduction) suits. What events had led up to this quitclaim?

Our new discovery of two previously unknown legal records, presented at a public event in October 2022, transforms our knowledge of the relationship between Geoffrey Chaucer and Cecily Chaumpaigne.[1] The two documents we introduced show that a third known life-record was also linked to the same dispute. The surviving records refute the long-held hypothesis that Chaucer may have raped Chaumpaigne; instead, the new records establish that Chaucer and Chaumpaigne were not opponents but belonged to the same party in a legal dispute with Chaumpaigne’s former employer, Thomas Staundon, who had sued them both under the Statute of Laborers (1349). Chaumpaigne’s quitclaims offered the most expedient legal path under the Statute of Laborers for both Chaucer and Chaumpaigne to demonstrate that she had left her employment with Staundon voluntarily, as opposed to being coerced or abducted, before commencing work for Chaucer.

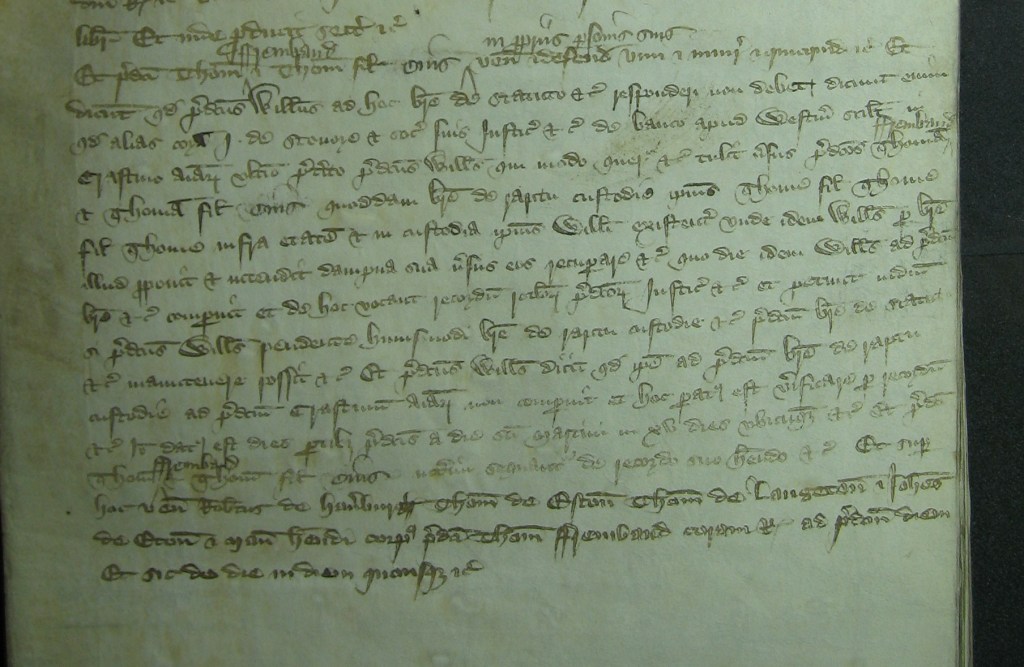

TNA, KB 136/5/3/1/2

The reception of our findings on Thomas Staundon’s 1379-80 case against Geoffrey Chaucer and Cecily Chaumpaigne, also published in October 2022, has been overwhelming.[2] As happens all too often with broad media coverage, the finer points are the first to be sacrificed.[3] This blog post, which will be followed by an expanded essay in the Chaucer Review in January 2024 (59:1), is an attempt to offer a fuller explanation of the reasons why Chaumpaigne’s two quitclaims are part of the Staundon case and therefore relate to the charge of procurement and the breach of her employment contract.

In addition, this post will present further evidence for the notion that English justices considered the procurement of an employee under the Statute of Laborers to amount to raptus custodie, or ravishment of ward. We will offer additional evidence in three areas: 1. the non-judicial language used in the quitclaims; 2. the precise timing of the quitclaims; 3. precedents and analogues that establish the use of raptus in cases of procurement under the Statute of Laborers.

1. Legal but not judicial

First, it is important to consider the legal status of each of the documents, particularly when determining the language used in each. The Chaucer-Chaumpaigne quitclaim (in all its versions) is often described as a ‘legal document’. The original quitclaim was not, however, produced by a legal institution. As such, while this document was legally binding, it was fundamentally a personal agreement between two individuals, and should be considered as such. It was not a judicial document (i.e., a product of the law courts themselves). While it bears similarities to the language and forms of the central law courts, the choice of language used – in this case raptus – was not part of a judicial formula but the preference of the scribe or those involved in the agreement, not necessarily that of the central law courts. The Close Roll enrolment of this, now lost, original quitclaim was also not judicial but a copy enrolled among the records of the English Chancery for preservation. Such enrolments – and the language used within them – remained private, and personal to those who had created the original quitclaim, their enrolment in the official records of central administration solely intended to ensure their preservation. In Easter 1380, in King’s Bench, however, Chaumpaigne’s interactions with the court were navigated through her attorneys, themselves clerks of the court, with the revised version of the text enrolled in the plea roll (this is the second release, discovered in 1993 by Chris Cannon).[4] This copy of the enrolment, unlike the first, can be described as a judicial or ‘legal’ document, specifically enrolled in the court to ward off an action there, as discussed below.

Why does this matter? If we are to consider the language of the quitclaim in the context of judicial records, such as actions under the Statute of Laborers as enrolled in the plea rolls, it is with the plea roll enrolment (which does not use the term ‘raptus’) that we must compare existing formulations. This is not to say that the language of the judicial record is the only source of ‘legal’ language to be compared against. The language of the justices themselves, recorded in the Law French of the Year Books (the earliest law reports) provides a further form of language – perhaps the most ‘legal’ of all – which could be searched for analogues to the phrasing of the 1380 Chaucer-Chaumpaigne quitclaim. Rarely do we find all the pieces neatly lining up.

As we previously noted, the word raptus in the original quitclaim suggests that something had happened in the circumstances around Chaumpaigne’s departure from service, but to compare the text of a private quitclaim against the judicial language of the plea rolls, and that of the Year Books is not as simple as some commentators have claimed. This may be the main reason why the phrasing de raptu meo, found in the Close Roll quitclaim, has not been found in the language of the courts. In other words, too much semantic pressure has been put on a wording – de raptu meo – that is not judicial and originated outside of the courts, in a private setting. As we show below, it is only in comparing all of these sources that the legal thinking behind the records might come to light, through which we are able to offer some potential contextual precedents.

2. The timing of the records

The precise timing of the two enrolments of Chaumpaigne’s quitclaim effectively demonstrates that these documents belong to the Staundon vs Chaucer-Chaumpaigne case, to guard against a pending action on the plea (civil) side of the King’s Bench. Both enrolments were made during the return day period known as the Morrow of the Ascension, which began on 4 May 1380, the original quitclaim having been made earlier that week. The first enrolment – that on the dorse of the Close Roll – took place on the first day of the return period, but it is the timing of the King’s Bench quitclaim that is particularly instructive.

Under the practice of the common law courts the first three days of each return day period were closely regulated. The plaintiff had to appear in court on each of these days before judgement against a defendant or the suing out of mesne process (the issuing of further writs) could proceed on the fourth day. The defendant had a similar responsibility should the plaintiff not appear. While the first three days were taken up by practical matters, the fourth day of each return day was the point at which a case would move to the next stage of the process, whether pleading or the issuing of a judicial writ authorizing the next step toward eventual outlawry.[5] It was on the fourth day of the Morrow of the Ascension, 7 May 1380, that the King’s Bench quitclaim was enrolled, and as such it was clearly copied in response to a pending action being brought in that court (specifically on the plea side of the court rather than the crown side), at that time.[6] Given that the King’s Bench plea rolls did not have a dedicated section for the enrolment of private deeds – unlike the plea rolls of the Common Pleas – and the fact that it had already been enrolled for preservation in Chancery, there is no reason for the second enrolment other than a pending action in the King’s Bench, that brought by Thomas Staundon in October 1379.

There does remain the question of whether any additional actions were brought against Chaucer by any of the parties involved (or others). Actions could be (and were) initiated in multiple courts simultaneously in order to try and force a settlement. Indeed, we suggested that the London enrolments of summer 1380 may have been the result of a secondary action taken in the city courts. We cannot entirely rule out the possibility of a second action brought on the plea side of King’s Bench. However, if a second action of any type had been brought in King’s Bench – and thus necessitated the quitclaims – there is a very narrow timeframe in which it could have been initiated. Any action in the court required an original writ to initiate the case. Without an original writ, there was no case to answer. As we can see from this timeline of the key events in the narrative, and the corresponding return days, the Brevia files for the period October 1379-June 1380 (that is, the bundles in which the original writ would have been filed) are almost entirely complete, with the single exception of a sole file currently missing from the otherwise extant records, that of the Morrow of the Ascension, the return day in which the King’s Bench quitclaim was enrolled.

What this means: Should any secondary action have been initiated, it is in this bundle, and only this bundle, that a writ for it could have been filed. There is, therefore, only a very small gap in the evidence in which such an action might be found, a gap which appears only as the case appears to have been coming to a close, and which was likely at a moment in proceedings in which Chaucer and Chaumpaigne were both employing the same legal representation. If an action was brought which required Chaucer and/or Chaumpaigne to appear before the court at the Morrow of the Ascension then it would likely have been initiated as late as April 1380, around the time Chaumpaigne was appointing her attorneys in the court – a point at which we believe the subject of procurement was discussed by both parties and their legal representatives.[7] It is important to note, however, that this bundle is also where we would expect to find any judicial writs in the case, which would also have initiated Chaucer/Chaumpaigne’s appearance and the enrolment of the King’s Bench quitclaim. No such writs, judicial or original, are present in the extant files.

3. A 1353 precedent

While we continue to believe that the arguments outlined under sections 1. and 2. offer conclusive evidence for our interpretation of these records, there also exists a relevant precedent for the Staundon vs Chaucer-Chaumpaigne case that corroborates our explanation of the preventative step of Chaucer and Chaumpaigne’s lawyers enrolling a quitclaim in the King’s Bench in Easter 1380.

In 1353, William de Holbeche, a London draper, sued his male servant, Thomas Frembaud, and the servant’s father under the Statute of Laborers, after Frembaud’s father removed his son from de Holbeche’s service. This part of the case is identical to Staundon vs Chaucer-Chaumpaigne. At the same time, de Holbeche also brought a writ of raptu custodie or ravishment of ward against the servant’s father for removing his servant. The case is summarized as follows:

W[illiam] de Holbeche sued a writ founded on the statute against Thomas F[rembaud] and his son [Thomas] of this that they had removed [Thomas Jr.], his servant and apprentice, out of his service at London. To this they came and said that, while this writ was pending, this same William had brought a writ of [‘raptu custodie’]directed to the Sheriff of London, supposing that they had ravished this same [Thomas] out of his wardship, returned on the Morrow of All Souls last past, to which writ he had appeared. Judgment if the plaintiff should be answered to this. And note, Shareshull C[hief] J[ustice of] K[ing’s] B[ench] held this a good plea. Therefore it was said to them that they should have their record.[8]

Justice Shareshull thought that the raptus defense was a ‘good plea’ or, in other words, that it is appropriate to use raptus is this context.[9] The charge of raptus lies here not because of Frembaud’s status as an apprentice: through the extensive plea record Frembaud is described a servant, and raptus custodie was regarded as a suitable writ because of his role as servant, a job that often required living in the employer’s household and thus being the responsibility of de Holbeche in this case. Chaumpaigne, being an unmarried servant in Staundon’s employ, was in a similar position.

The notion that raptus as procurement in the context of the Statute of Laborers appears to be attached to the status of ‘servant’ receives further support from a case dating to 1443. Here Richard Newton, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, maintains that raptus lies in cases of servants being taken out of their service under the Statute of Laborers. Expressly, this justice says that being an apprentice entails being a servant, and the feasibility of the raptus action is therefore based on the status of being a servant:

Newton, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas: if I bring a writ of Trespass for ravishment of my son and heir being in my service, I think (voile bien) that this writ is no good, because I cannot constrain him (my son) to serve me unwilling (sans son bon gre); but taking my apprentice then being in my service is a good writ, because that he is named apprentice includes in itself that he is my servant.[10]

Thus, we can see a connection between the language of raptus and the Statute of Laborers, whereby Chaumpaigne could be sued under the Statute of Laborers, while Chaucer could potentially have also expected an action (perhaps directly to the Sheriffs of London) for raptus custodie, in the context of the Statute.

Even in retrospect, English justices considered the procurement of an employee under the Statute of Laborers to amount to raptus custodie, or ravishment of ward. In fact, raptus in cases of procurement belongs to the history of the non-compete clause and forms part of the development of English tort law that still governs contracts. The landmark 1853 case of Lumley vs Gye ([1853] 2 E & B 216; 118 ER 749) was a foundational English tort law ruling that established that one may claim damages from a third person who interferes in the performance of a contract by another. This case is being taught in law schools to this day. At the heart of the dispute was Johanna Wagner, a singer hired by Benjamin Lumley to sing exclusively at Her Majesty’s Theatre for a period of three months. Wagner was lured away by Frederick Gye, the proprietor of Covent Garden Theatre, who offered her a larger salary and induced her to break her contract with Lumley. An injunction was issued to stop Wagner from performing at Covent Garden Theatre, but Gye convinced her to ignore it. As a result, Lumley sued Gye for damages to recover his lost income.

The case bears similarity to that brought by Staundon against Chaucer and Chaumpaigne, not least because both cases were argued in the court of King’s/Queen’s Bench.[11] It is no surprise that the fourteenth-century Statute of Laborers loomed large in the judges’ reasoning during the Lumley vs Gye case. When the justices issued their opinions during the 1853 case, raptus was explicitly regarded as a correct plea for procurement under the Statute of Laborers. In fact, throughout the courtroom discussion the judges referred to several precedents that establish that the procurement of a person’s ward to depart from them fell under the plea of ravishment of ward (raptus custodie), based on the Statute of Laborers. The last-reported judgment in this case, Justice Coleridge’s dissent, invokes a 1409 case from the Year Book for Michaelmas 11 Henry IV, fol. 23r, pl. 46 in which John Colepeper, a Justice of the Common Pleas, persuaded William Hankford, later Henry V’s Chief Justice of England, that ‘if a man procure my ward to go from me, and he goes by his procurement, I shall have ravishment [raptus]of ward against him’.[12] Here it is worth noting that among the early responses to our find, Timothy Noah’s considered piece for the New Republic (‘Chaucer Was Cleared of Rape, but What He May Have Done Instead Remains Illegal Today’) is the only instance of spotting the relevance of Staundon vs Chaucer-Chaumpaigne for modern contract law in that it highlights the non-compete clause.[13]

Not only do the three cases from 1353, 1409, and 1443 show that raptus was an appropriate plea for servants procured out of their contracts under the Statute of Laborers, but the foundational Lumley vs Gye case from 1853 demonstrates that Staundon vs Chaucer-Chaumpaigne constitutes part of the historical pedigree and bedrock of the material discussions in the development of modern tort law.

The authors would like to thank Andrew Bell, Gwen Seabourne, Marion Turner, and the editors of the Legal History Miscellany blog for their insightful comments and corrections.

Euan Roger is Principal Medieval Records Specialist at The National Archives. His research explores the Chaucer life-records, pre-modern health, community and disease, and the records of medieval government and the central law courts.

Sebastian Sobecki is Professor of Later Medieval Literature in the Department of English at the University of Toronto. His research covers a wide area of medieval literary culture, especially law, travel, politics, authorship, manuscripts, and palaeography.

Banner Image: From the The Canterbury Tales, c. 1410, British Library, Lansdowne MS 851, fo. 2, © British Library Board, shared via a CC-BY licence.

The other images are provided courtesy of The National Archives (Kew).

Notes:

[1] Euan Roger and Sebastian Sobecki, “Geoffrey Chaucer, Cecily Chaumpaigne, and the Statute of Laborers: New Records and Old Evidence Reconsidered,” Chaucer Rev. 57, no. 4 (2022): 407–33, https://doi.org/10.5325/chaucerrev.57.4.0407. See the entire issue of the Chaucer Review on this topic, 57:4, which we co-edited.

[2] For a particularly thoughtful response from a legal historian, see Gwen Seabourne’s post on the blog of the University of Bristol Law School (5 June 2023): https://legalresearch.blogs.bris.ac.uk/2023/06/escapades-and-labour-chaucer-chaumpaigne-and-legal-history/

[3] Given the wide coverage in the media, readers will have no difficulties identifying some of the less accurate news items. However, even the strongest articles on our find tend to lead with attention-grabbing headlines, such as Jennifer Schuessler, “Chaucer the Rapist? Newly Discovered Documents Suggest Not,” New York Times, October 14, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/13/books/geoffrey-chaucer-rape-charge.html.

[4] For this discovery, see Chris Cannon, “Raptus in the Chaumpaigne Release and a Newly Discovered Document Concerning the Life of Geoffrey Chaucer,” Speculum 68, no. 1 (1993): 74–94.

[5] In the plea rolls this is commonly noted by the formula “X. offered himself on the fourth day against Y.”

[6] The plea (civil) and crown side of the plea rolls were physically distinct within the roll, and each had separate administrations and series of Brevia files. The enrolment of the quitclaim in the plea section clearly demonstrates it was related to an action on the plea side of the court. No reference to Chaucer, Chaumpaigne or Staundon has been found among the Brevia Regis files (TNA series KB 37).

[7] The delay between the initiation of an action and the assigned return day is known to have been variable. If, however, we use the example of Staundon’s initial writ under the Statute of Laborers, and the return day assigned for Chaucer and Chaumpaigne to appear, then we might expect a gap of roughly four return days between initiation of a case and the initial assigned return day. This places any potential secondary action on the plea side of the court as being initiated around the Quindene of Easter (9 April) at the very time Chaumpaigne was appointing her attorneys in the court, against Staundon not Chaucer

[8] The precedent in question is 27 Edward III (1353), fols. 135a-b, Lib. Ass. 21. Seipp number: 1353.146ass. Quoted from the Seipp Database, https://www.bu.edu/phpbin/lawyearbooks/display.php?id=12519. The names and the exact quotation of ‘raptu custodie’ have been supplied from the actual record, TNA KB 27/373, rot. 73d: http://aalt.law.uh.edu/E3/KB27no373/bKB27no373dorses/IMG_1773.htm (image 1773). This case is also mentioned by Bertha Haven Putnam, The Enforcement of the Statutes of Labourers During the First Decade After the Black Death, 1349-1359 (New York: Columbia University, 1908), 185, 416.

[9] We are grateful to Gwen Seabourne for helping us to clarify Justice Shareshull’s remark.

[10] 22 Hen. 6 (1443), Mich., fols 30v-33r, pl. 49 (Seipp number: 1443.108): https://www.bu.edu/phpbin/lawyearbooks/display.php?id=18322

[11] Both cases, Staundon and Lumley, were pleaded in the same court King’s/Queen’s Bench. (Queen’s Bench in the case of Lumley vs Gye because it took place during Victoria’s reign).

[12] Cited in Lumley v Gye [1853] EWHC QB J73 (EWHC (QB) January 1, 1853).

[13] Of the fifty or so news articles published in the weeks immediately following our announcement of October 11, 2022, to our knowledge only one article responded to the implications for labor laws and servants, Timothy Noah, “Chaucer Was Cleared of Rape, but What He May Have Done Instead Remains Illegal Today,” The New Republic, October 18, 2022, https://newrepublic.com/article/168172/chaucer-rape-servant-noncompete-illegal.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.