By Cassie Watson; posted 19 September 2023.

What does syphilis have in common with acid throwing? This isn’t a trick question or a macabre joke: the answer is the 1861 Offences Against the Person Act, a statute that provided a flexible means of penalizing harmful acts. Its many provisions revolved around the concept of ‘bodily harm’, and by 1910 at least one well-known forensic expert used both the transmission of syphilis and the throwing of corrosive fluids as examples of ‘grievous bodily harm’ — a term that could not be defined without reference to the law.[1]

Few Victorian doctors would have denied that diseases like syphilis and puerperal fever did cause grave physical damage; indeed, they were frequently fatal. However, influenced by the 1837 Offences Against the Person Act, lawyers and judges tended to consider ‘harm’ to be caused by some weapon or instrument.[2] Thus, for some, the effects caused by a dangerous disease could not constitute an assault under the 1861 Act. Furthermore, the notion of mens rea is central to the criminal law, and moral culpability tended to be judged on a case by case basis. Thus, while the deliberate throwing of any corrosive fluid at someone was explicitly criminalised by the statute,[3] the effect of negligent or wilful disease transmission was not even mentioned.

Doctors, Disease and Law

This did not mean that the 1861 Act could not apply to such a scenario, but prosecutors had to be nimble with their arguments. There was no uniform agreement about what constituted a guilty mind, but in theory judges tended to agree that the act in question should be both unlawful and dangerous. In the case of a doctor’s responsibility to their patients, according to A. H. Manchester, “the courts found it difficult … to elucidate the extra degree of negligence which would distinguish liability for negligence at civil law from criminal liability for manslaughter.”[4]

Doctors, for their part, had long been alert to the possibility that professional negligence (‘ignorant malpractice’) might lead to a suit for damages;[5] and charges of manslaughter were regularly brought against medical practitioners in midwifery cases where the mother had died from blood loss.[6] But doctors do not seem to have feared the potential legal consequences of negligently transmitting a virulent disease, even though this risk was the source of some popular anxiety.[7] According to the redoubtable campaigner Frances Power Cobbe (1822–1904), doctors “ran all over town” carrying “millions of disease germs on their persons and clothing,”[8] yet the Infectious Disease Notification Act of 1889 did not impose any penalties on doctors who transmitted disease. Moreover, experts on syphilis noted that the disease might become established in the hands, “especially among physicians infected in the practice of their profession.”[9]

Nonetheless, by 1900 medical practitioners were still avoiding legal scrutiny. According to a London magistrate, “Persons suffering from infectious diseases wilfully exposing themselves are liable under the Public Health Act [1875], but so far as I can see persons who attend infectious cases can mix with the community without any penalty.”[10]

He had a good point. Doctors who spread disease don’t seem to have been prosecuted at all, while the small number of midwives who were prosecuted were mostly acquitted. Thus far I have found only one conviction, that of Martha Schofield, at the Leeds assizes in 1883.

The Trial of Martha Schofield

In January 1883 Martha Schofield, a widow aged 63 with a large midwifery practice near Sheffield, was charged with having unlawfully and maliciously caused grievous bodily harm to a number of women whom she had attended, and also to their husbands and children. The prosecutions were initiated by the Health Committee of the Town Council, following preliminary investigations made by the Medical Officer of Health. Evidence was given to show that for more than 15 months she had been suffering from a highly contagious disease, syphilis, and that she had been warned by two doctors not to practice. The magistrate committed her to the Leeds assizes: on 12 February 1883 she was tried before Mr Justice Day.

The extensive press reports of her trial provide the gist of the evidence against her and the rationale for the jury’s decision. Essentially, Schofield had contracted syphilis 18 months before, in the course of her duties as a midwife. She had consulted a number of doctors, all of whom told her “the nature of her complaint, and cautioned that on no account must she attend any patients while the disease remained uncured.”[11] And yet, between late August and early October 1882, she infected two of her patients, the newborn infant of a third, and the three women’s husbands. She had lied to one doctor about the nature of a finger injury (an external manifestation of the disease) that she attempted to cover with a tip snipped from the finger of a glove. One of the medical witnesses told the court he had been in practice 42 years, and had seen only four such cases (of disease transmission).

In defence, Schofield’s barrister, Mr. E. Tindal Atkinson, objected to the indictment on the grounds that there were three counts under the statute (of 1861) and three under the common law, but did not deny that she had knowingly infected and injured the victims. Instead, he argued that the law did not cover her acts. At common law, the indictments were for being a common nuisance. But, at common law, there must be an offence against some public authority and in some public place: but here the complaint was made of a wrong committed against a private individual. Under the statute, an offence must rest upon the fact of there being an actual assault.[12]

In reply, the judge stressed both the applicability of the common law, and by extension the statute,[13] and Schofield’s guilty mind: “It would shock him if he could think that a person might communicate such a disease as the one in question, however unintentionally; and was it to be held not to be an offence because the victim had not died? … Was not the spreading of such a disease as this an injury to the public?” To the jury, he noted that even if Schofield had not been warned at all, he would still have held that she was criminally liable, “for it was beyond all question that she had attended at least upon one of the women who had complained that day … after she had been made aware that already others whom she had attended were suffering from it.”[14]

A different newspaper reported this exchange between Atkinson and Day in even more illuminating detail:

“His Lordship said he could not conceive that it was not an offence at common law to communicate a disease. Could it be said that in a case where death ensued a person could be hanged for murder, that if death did not ensue such a person would not be punishable? Mr Atkinson replied that an individual wrong could not be made into a criminal offence. His Lordship: It must be a public offence, not in the sense of injuring many people, but in the sense of its character. An assault and battery is necessarily a private offence, but it is also a public wrong. Mr Atkinson: There you have a breach of the peace. His Lordship: There is the case of administering poison with intent to kill; show me that is not an indictable offence, then I will not proceed with this. Mr Atkinson said that for one person to kill another was an offence against the public and the public safety. His Lordship: Surely to attempt to give people grievous bodily disease is against the public interest and safety. The State has an interest in the life, liberty, and good health of its subjects, and a person who injures another would, I should have thought, injured the State, and commits a wrong.”[15]

After deliberating for 70 minutes the jury found Schofield guilty on all counts, “but unanimously recommended her to mercy on account of her previous good character and her old age, and because they thought she had displayed a great amount of ignorance in the matter.”[16] She was sentenced to 12 months’ incarceration in Leeds Prison. According to forensic expert John Glaister, writing years after the event, 45 persons in all were infected either directly or indirectly by the defendant.[17]

Conclusion

Interpretations of mens rea were, as A. H. Manchester has stated, the result of “a changing morality and attitude to crime.”[18] Schofield’s trial was a case of first instance,[19] and prosecutors at the Central Criminal Court in London tried at least three times over the next twenty years to prosecute midwives for similar offences. These prosecutions failed, probably because the unfortunate victims had died and the women were charged with manslaughter. The Director of Public Prosecutions evidently perceived criminality in the transmission of disease through professional negligence, but it was difficult to establish two crucial points. First, the necessary guilty mind: if the midwife had taken some steps to limit the degree to which she could be accused of reckless conduct, that undermined a charge of manslaughter. Second, in an age when epidemic disease was common, it was difficult to prove that the midwife had indeed been the source of the fatal infection. If the victims had survived and their midwives had been charged with assault, perhaps the prosecutions might have succeeded.

This does not explain why doctors were not similarly prosecuted under the Offences Against the Person Act, but the responses to Frances Power Cobbe’s letter to The Times in 1889 suggest a possible reason. Although members of the public accepted that, “as sometimes happens, infection is communicated to a whole family by medical carelessness,”[20] by and large this was not believed to be a general problem; and doctors were assumed to take necessary precautions as a matter of self-interest. Thus, “while it might be well that there should be a code authorised by the College of Physicians, most people will agree with the Lancet that any legislation having either that or the notification of doctors as its object would be futile and superfluous.”[21] The usual, necessary, proper or reasonable precautions that doctors might cite in exculpation were, of course, defined by the medical profession itself.

Images

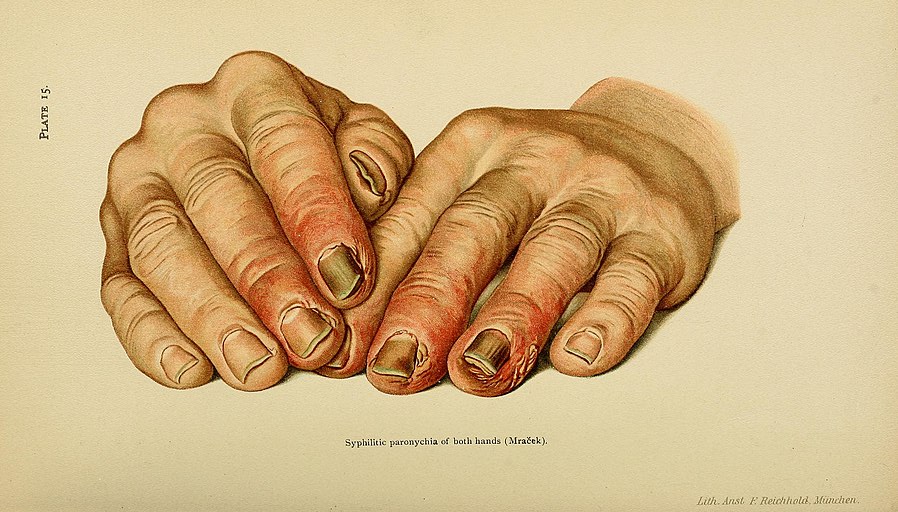

Main image: Illustrative plate showing hands diseased with Syphilis, accompanying plate description reads ‘Syphilitic Paronychia of Both Hands.’ n.d. Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

Portrait of Frances Power Cobbe. Image from frontispiece of autobiography Life of Frances Power Cobbe, by Herself, Volume 1. London: Bentley, 1894. Wikimedia Commons.

Plate 15: ‘Syphilitic paronychia of both hands (Mraček)’. James Nevins Hyde and Frank Hugh Montgomery, A Manual of Syphilis and the Venereal Diseases, 2nd edn (Philadelphia: Saunders, 1900), 132. Wikimedia Commons.

References

[1] John Glaister, A Text-book of Medical Jurisprudence and Toxicology (Edinburgh: Livingstone, 1910), 247-248.

[2] An Act to amend the Laws relating to Offences against the Person, 1 Vict c.85 s.4.

[3] Katherine D. Watson, Acid Attacks in Britain, 1760–1975 (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, forthcoming October 2023), 6-9.

[4] A. H. Manchester, A Modern Legal History of England and Wales 1750–1950 (London: Butterworths, 1980), 198-204; quotation on p. 201.

[5] See for example, Michael Ryan, A Manual of Medical Jurisprudence, and State Medicine, 2nd edn (London: Sherwood, Gilbert, and Piper, 1836), 178.

[6] Alfred S. Taylor, A Manual of Medical Jurisprudence, 12th edn, ed. Thomas Stevenson (London: Churchill, 1891), 315.

[7] Saffron Walden Weekly News, 23 November 1889, 4; Liverpool Echo, 16 November 1889, 3.

[8] Frances Power Cobbe, “The Notification of Infectious Doctors,” The Times, 15 November 1889, 13.

[9] James Nevins Hyde and Frank Hugh Montgomery, A Manual of Syphilis and the Venereal Diseases, 2nd edn (Philadelphia: Saunders, 1900), 136.

[10] South Western Star, 10 August 1900, 5.

[11] London Evening Standard, 13 February 1883, 3.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Sheffield Independent, 13 February 1883, 8.

[16] London Evening Standard, 13 February 1883, 3.

[17] Glaister, Text-book of Medical Jurisprudence and Toxicology, 248.

[18] Manchester, Modern Legal History, 202.

[19] London Evening Standard, 13 February 1883, 3.

[20] Western Times, 30 November 1889, 4.

[21] Eastern Morning News, 25 November 1889, 2.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.