Guest post by Daniel Gosling and Charlotte Smith, 16 October 2023.

In June 2023, The National Archives (UK), generously supported by The Journal of Legal History/Taylor & Francis and British Online Archives, hosted the inaugural Legal Records Jamboree, showcasing legal records from across their collections. A variety of people and groups attended the day, and speakers gave 5-minute presentations on their chosen document before showing off the record in more detail in the Map and Large Document Reading Room at Kew.

In this four-part blog series, Dr Daniel Gosling and Dr Charlotte Smith, Legal Records Specialists at The National Archives, provide an overview of the documents on show during the day and reflect on the different types of legal record held at The National Archives.

This penultimate blog examines the legal records relating to verdicts and judgments.

Finding evidence of judgments can be challenging. Not all court cases made it to this stage, and if the parties arbitrated out of court, or the case was ended in some other way (e.g., if one of the parties died) then there wouldn’t be a formal legal record created to note this. So, when there is a record of this stage, the end of the formal legal proceedings, it is a satisfying conclusion to research into a particular case. At the jamboree, we had a wide range of records relating to verdicts and judgments, from the fifteenth century up to the present day.

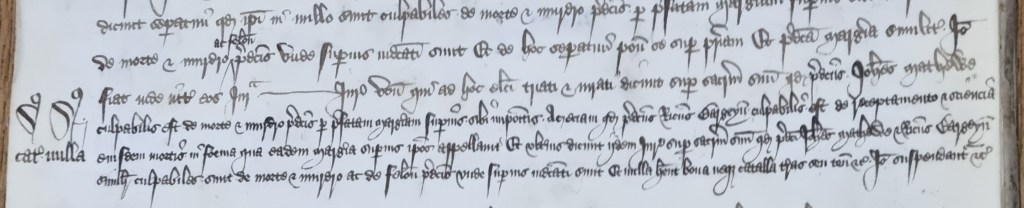

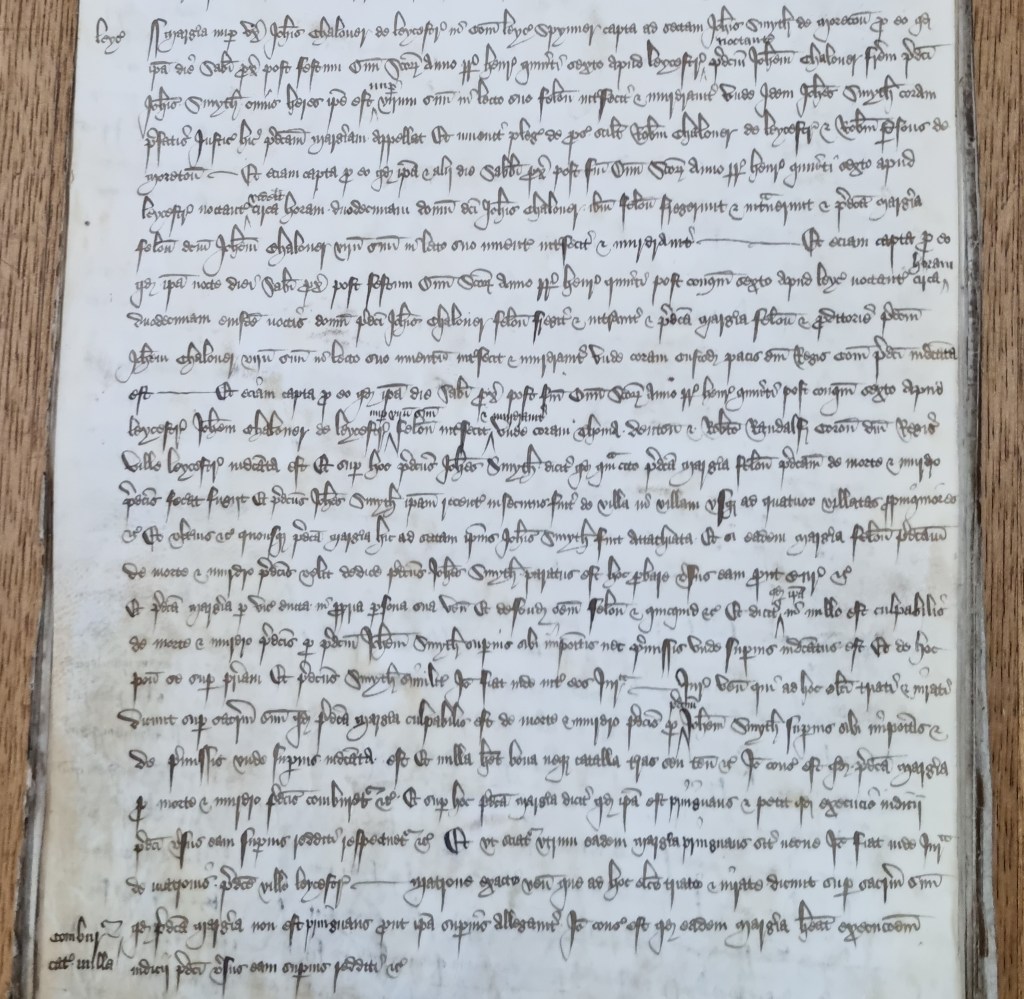

For the early records of the common law, verdicts were recorded in the gaol delivery rolls and files. These rolls include records of pleadings, calendars of prisoners, and copies of commissions. At these sessions, justices from the central law courts could hear local cases relating to a range of criminal activity, from robbery to murder. For the jamboree, JUST 3/195 was on display, an early fifteenth century roll for Derbyshire, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, Northamptonshire, Nottinghamshire, Rutland, and Warwickshire. The specific case(s) highlighted showed how punishments (and the crime for which a party was accused) could differ depending on the defendant. In the first entry, Margery Chaloner, the wife of John Chaloner of Leicester, accused John Mathewe and Richard Bargeyn of killing her husband in his bed on a Saturday night in November 1418. The record notes that the men were found guilty of this murder and ordered to be hanged.

In the subsequent entry, however, Margery Chaloner was the defendant, accused of being complicit in her husband’s death. She was found guilty of petty treason, for which the punishment (for a woman) was to be burned to death.

Capital punishment was a common feature of the common law into the modern period, and another document on display, ASSI 23/8, described a similar fate for a convicted criminal, several centuries after Margery Chaloner’s conviction. For the records of the assize courts the survival of records relating to verdicts (and, indeed, other records relating to these courts) is inconsistent, reliant on their safe passage across the country on circuit, and thereafter reliant on the clerks of assize looking after the documents in their care before they made their way into the central repositories. When they do survive, however, they are often rich with information relating to these court cases. For judgments and verdicts, the gaol books are our best source of information. These books, arranged by circuit, relate mainly to proceedings under commissions of gaol delivery and contain details of prisoners sent for trial, usually with a note of the plea, verdict, and sentence. The volume on display for the jamboree, a gaol book for the Western Circuit, describes the fate of James Hill, also known as ‘John the Painter’, the revolutionary who was sentenced to be hanged for arson during the 1777 Lent Circuit, for (among other things) “feloniously…setting on fire…a building erected in a dockyard of the King called the Ropehouse”.

As with records relating to pleadings, records describing judgments and verdicts for equity court cases were created and arranged in a slightly different way to the common law cases. For the court of Chancery, the main way to find out if a case reached a verdict, and what that verdict was, is to consult the entry books of decrees and orders for the court. Orders were issued by the court during the course of the case, such as ordering witness statements to be taken, or postponing a case until all the evidence had been produced. The final decree recorded the judgment. Indexes to these volumes, which describe cases by short title and are arranged alphabetically by plaintiff surname, allow researchers to find the volumes and relevant folios, but they still must wrestle with the size of these volumes, which highlight just how much business the Chancery clerks were conducting on a daily basis. For the jamboree, C 33/232, the entry book for 1668, was on display, demonstrating the huge size of these volumes.

Another way to identify Chancery verdicts is by checking whether the decree was enrolled on the Decree Rolls for the court (C 78). These rolls contain decrees, orders, and dimissions which were enrolled to provide a permanent and authoritative record of final judgment in the court of Chancery. At the jamboree, C 78/17/7 described the case between Richard Bertye, esq, husband to Katherine, the duchess of Suffolk, on the one part, and Walter Herenden on the other, concerning a lease made by Bertye and his wife of lands in Lincolnshire.

When it comes to the court of Chancery, researchers really benefit from the officers of that court’s record-keeping and administration from a relatively early period. As such, there are other record series that can supplement the decree and order entry books for these cases. C 38 contains the reports of the Chancery Masters on matters referred to them for their investigation and opinion. These reports could be lengthy and include detailed material from the pleadings and other papers being examined by the master. Such a report from C 38/37, being the 1619 volume for Q to Z plaintiffs, includes a detailed schedule of the debts owing to the creditors of Robert Tiffyn, deceased.

The court of Star Chamber, the judicial arm of the King’s (and Queen’s) Council during the Tudor and Stuart periods, heard all manner of cases, including those of riot, corruption, libel, and fraud. However, we cannot know the outcome of many of these cases because the decree and order books, the main record type that details this information, for the court were lost in the later seventeenth century. But, some evidence of these decrees and orders survives by chance, such as STAC 8/196/25, on display at the jamboree, an original decree of the court from 1618. This decree concerns the suits between Sir Thomas Lake, secretary of state, and Thomas and Frances Cecil, the earl and countess of Exeter (in STAC 8/196/23-24 and STAC 8/111/26). Frances Cecil was accused by Sir Thomas Lake of trying to poison him and his daughter Ann Lake, Lady Roos. A counter-suit brought by Thomas Cecil accused Lake of slandering his wife, by also claiming that she had committed adultery with William Cecil Lord Roos, her step-grandson. However, this document is also notable because King James I attended the court in person and presided as judge in the case. This was the last time that an English (or British) monarch sat directly in judgment over their subjects.

Another volume on display at the jamboree was DL 5/4, a volume of proceedings of Henry VII’s Council Learned in the Law, including the judgments of this association of the king’s trusted councillors. This council developed from and relied upon the skilled personnel and administrative structure of the king’s private estates as duke of Lancaster, and so records of these proceedings can be found in the Duchy of Lancaster (DL) collection at The National Archives. Details of the council’s decisions are known from the contents of two entry books of acts and orders, DL 5/2 and 5/4.

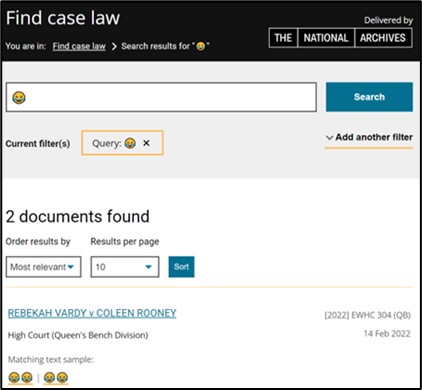

To bring these records relating to judgments up to the present day, the jamboree also included a presentation from Find Case Law. As of April 2022, The National Archives receives selected court judgments and tribunal decisions for permanent preservation and publication on the Find Case Law service. Currently, they receive judgments from the Privy Council, UK Supreme Court, Court of Appeal, High Court, Upper Tribunals, and Employment Appeal Tribunal. At the jamboree, the Find Case Law team demonstrated how you could even search for emojis in cases, such as those produced as evidence from the WhatsApp correspondence of Rebekah Vardy (Vardy v Rooney [2022] EWHC 2017 (QB)). It’s a far cry from the comparatively complex calendars and indexes required to search for medieval and early modern judgments.

One of the digital contributions to the jamboree reflected on this new Find Case Law service and the underlying dataset of digitised judgments held by The National Archives. The contributor Václav Janeček pointed to some potential difficulties around the licencing regime concerning the use of this data for computational (typically statistical) analysis. Building on his research, Janeček argued that the arguments for and against access to judgments conflate different understandings of what judgments are. On one view, judgments are seen as a “jurisprudential” category, whereas the other view regards them as something “factual”. Once it is understood that these views and the claims based on them do not fight over the same territory, it should be easier to make judgments more widely available, including for the purposes of computational analysis of judgments as bulk data.

With records relating to judgments and verdicts, researchers can get some closure on an individual case that they are working on, as these records describe the formal end to these legal proceedings. In many cases, they also provide details of the rest of the legal process as well. But, just because a court case had ended and the guilty parties had been punished, did not mean that records did not continue to be created relating to legal processes and the law. In our final blog, we reflect on these “other” types of legal records, including legislation and law reports.

Documents selected by Gwen Seabourne, Ralph Thompson. Ruth Selman, David Foster, Fleur Stolker, Dan Gosling, Sean Cunningham, Nicki Welch, and Václav Janeček.

If you have a question about the Legal Records Collections held at The National Archives, Dan and Charlotte welcome enquiries from interested researchers.

All documents © The National Archives. Photos taken by Dan Gosling.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.