Guest post by Richard W. Ireland, 13 November 2023.

This piece is about delight.

Legal history being, as its name suggests, a hybrid discipline, it sometimes has to defend itself, to justify its importance, even to assert its centrality. Some lawyers regard it as an indulgent diversion, an “easy” subject for students who need a rest from “hard” law, whilst some social historians see it as a pedantic and sometimes unnecessary distraction from the real issues of the exercise and response to power within society. Certainly I have heard both views expressed. The readership of this blog will, I’m assuming, have no need for the refutation of either view, since both are patently nonsense. What I do want to propound here is a more personal reason for the study of the history of law, one which we perhaps wisely keep to ourselves: legal history holds the capacity for genuine delight.

I suspect (I hope) that we’ve all experienced it. There are the methodological joys: the thrill of reading something which perhaps has lain unread for hundreds of years, the case which suddenly reveals that our hunch was right, the dots which join to form a pattern, and there are joys which inhere in the nature of the sources: the accidental poetry of a witness deposition, the low farce of a courtroom exchange, the elegance of an argument.

The book which sits on the desk in front of me as I write is small, about 4 inches by 7½ as its owner (and I) would measure it, 11 x 17 cm for others. Sold by Carter of Regent Street, London it has a green binding with gold tooling. I bought it in the pre-Covid days from a well-known London art dealer and then had it professionally conserved by the excellent team at the National Library of Wales. I would take it out and look at it with immense pleasure for the sheer beauty of its contents. Then Covid closed the libraries and after that I had obligations to editors and to publishers. The book and its contents remained unresearched. I still have a long way to go with it, but I have just started to penetrate its mysteries.

It is a sketchbook. On the first opening it bears, in very faint pencil the words “S. Platt Western Circuit”, and below, rather more distinctly:

Characters

Not

CaricaturesSketches taken from life principally

in Court on the Westen Circuit

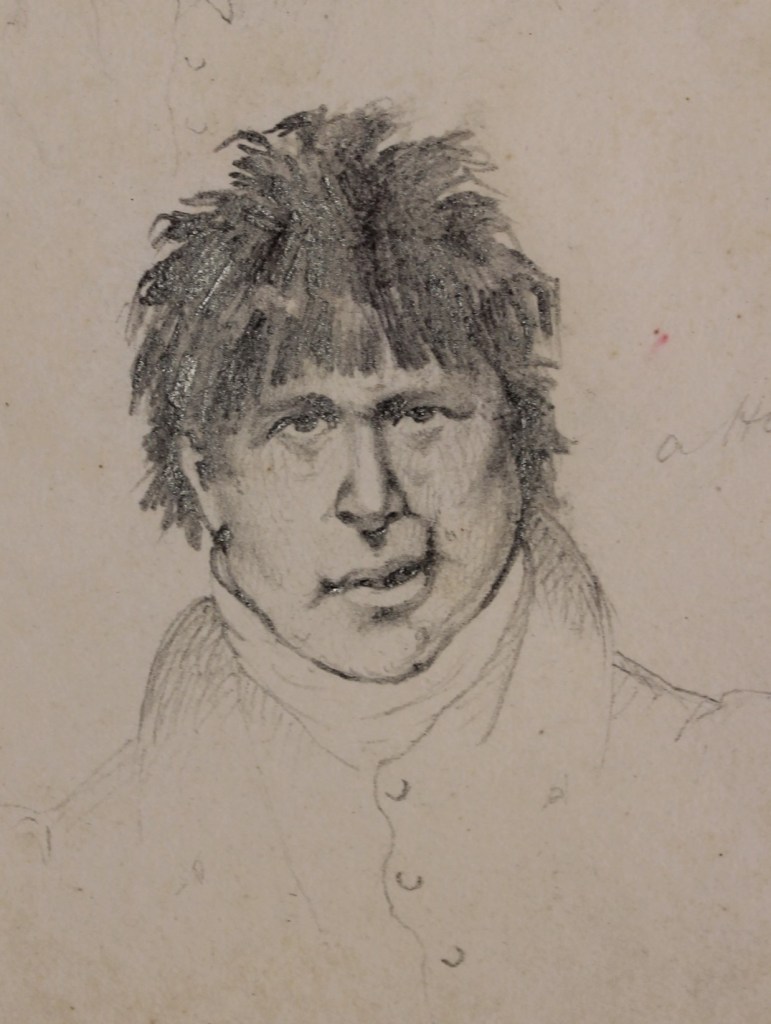

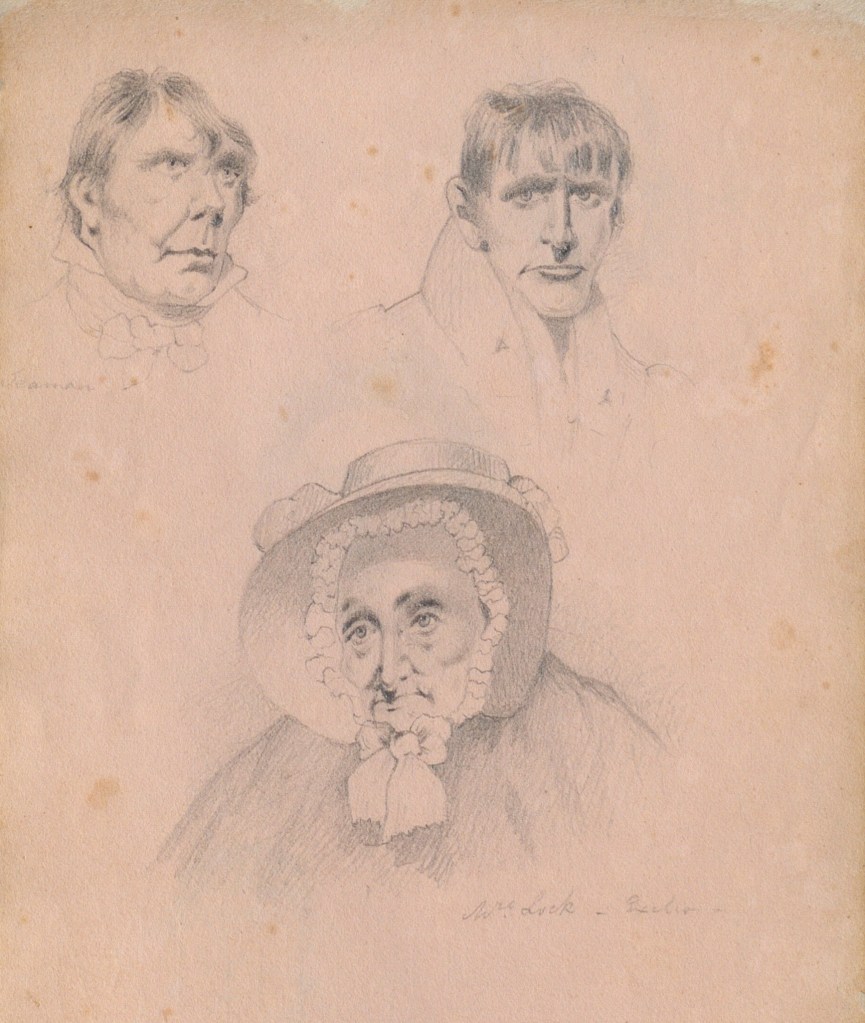

And then follow the portraits: vivid, immediate and breathtaking in their technical skill. They are small, and reproduction here will thicken the precision of the line and reduce their jewel-like intensity, but I hope that you will get an impression.

I think that I have successfully identified the artist. Samuel Platt Jr, barrister of Symonds Inn, had been the Associate of the Western Circuit mentioned in a practice manual of 1833.[1] I still have work to do on him, but much more remains to be done to discover the identities of those he drew as he waited in court. Only four names are given, and these seem not to be those of offenders, for they include the dapper “Mr Bishop Clerk of Arraigns” and the elegantly coiffured and extravagantly hatted “Miss Wassington Torquay”. Most have no identifying notes and of those that are given, some relate simply to their role in the case (“Prosecutor”, “Juror”, “Prisoner Transported”) or their occupation (“Horse Dealer”, “A Cornish Ostler”). Others (“Modesty”, “An Outdoor Man”) seem to comment on the subjects’ appearance, or are given a soubriquet (“The Swindon Rider” or “Friend [possibly, though the name is almost illegible] An Attorney of Horse Pond Notoriety”). Of the majority, however, no information is given beyond the sketch itself. There are certainly no dates in the book at all. The art dealers dated it to the 1830s, based, no doubt, on the style of dress represented, but I had always thought it rather later, as “provincial” fashion could lag behind the metropolitan styles. Art dealers know the quality of the work they handle, but are lamentably ignorant of criminal justice history: this one thought the characters therein were all from London, whilst I write this in a study with two pictures on the wall, both of which were being sold as “Newgate”: one is of Millbank, the other of Pentonville.

My task, which I have barely begun in earnest, is to identify as many of the individuals as I can, by matching convictions and crimes to sittings of the Assize. But surely, you mutter, there’s already enough in what you have already said to do this. Perhaps; but despite access to some computer searchable records, I have found this difficult. My greatest hope was for the rather depressed looking young woman whose picture carries the legend “Tried at Dorchester for Murder-Acquitted”, which surely ought to have been easy to find. But I could not, at that time, see her anywhere. We’ll come back to her.

As it turned out, I found the key (forgive me) in Mrs Lock. This sturdy, elderly woman with sad eyes and a close-fitting bonnet was simply captioned “Mrs Lock Exeter” and she is pictured on the same page as two rather intense, thin faced younger men, one of whom is captioned, so faintly as to be again almost illegible, “Seaman” (Fig 2). Mary Ann Locke was the wife of a Dorchester post-master who appeared as a witness in a forgery trial of Joseph Davies and Thomas Byrne who were both sentenced to seven years transportation.[2] I suspect that these men are those sketched on the same page.

Now a time frame suggested itself, and allows of a hypothesis for the identity of a most curiously labelled figure, in which the accent as well as the appearance of the individual is captured: “An anti-Catholic. I give my voice for the prodiſsant religion” (Fig. 3).

There is a libel case from the 1850 Assize in which the Rev’d George Prynne brought a criminal libel case against the editor of the Plymouth Journal, which had accused him of being a Puseyite and of fathering a bastard child. The former allegation seems to have had some foundation, but the latter was found to relate to the wrong man: the fornicator involved was, it seems readily accepted, another preacher by the name of Burgess! Nonetheless a verdict of Not Guilty was returned, to the applause of the attending public.[3]

The position of the drawing of the accused murderess between these two cases suggested that I ought to find her in an intermediate sitting of the Assize (Fig. 4). But, ignoring the advice I had so often given to students, I failed to question either the accuracy of the source or the authority of the computer searches (or indeed my own preconceptions: I assumed an infanticide). Simply going systematically through the records found the answer exactly where it should have been. Sarah Bird was prosecuted, but at Exeter rather than Dorchester, alongside her husband in March 1850 for the murder of 14 year-old Mary Anne Parsons, whom they had taken from the Union to act as a servant. The cruelty suffered by the girl was abominable, but the jury acquitted, on the direction of Talfourd J, on that difficulty which survived for many years until the law was changed: that it was not clear which of the defendants, both of whom had beaten her, had administered the fatal blow.[4]

I have much work still to do on the sketchbook. My conclusions to date remain tentative, the task for the future rather daunting. Does it matter? To simply state that these pictures restore the human face to the reports and statistics of nineteenth-century crime is banal, even though (and I speak as someone who has worked for many years with early photographs of prisoners) they inject more personality and vitality to their subjects than any other source I know. But I want to return to where I began this piece. Despite the very real horror which cases such as the last-mentioned evidence, my overwhelming reaction to the discovery of the totality of this wonderful, skilled, quasi-Dickensian catalogue of characters is one of excitement, of the sheer thrill of discovery. Legal history has the capacity to challenge, inform, explain, but also to delight. I hope that the reader will feel some of that too.

________

Author bio: I taught Legal History at Aberystwyth for forty years and have researched and written widely, particularly on the history of crime and punishment. My books include A Want of Order And Good Discipline: Rules, Discretion and the Victorian Prison (University of Wales Press, 2007) and Land of White Gloves? A History of Crime and Punishment in Wales (Routledge, 2015). Two earlier works, Imprisonment in England and Wales: A Concise History (with C. Harding, W. Hines and P. Rawlings) and Punishment: Rhetoric, Rule and Practice (with C. Harding), have recently been re-issued by Routledge. I have a passion for visual art and have written on representation of law and crime in painting and early photography.

rwi@aber.ac.uk

All illustrations are from the sketchbook. Copyright in the images remains in the author.

Notes:

[1] G. B. Mansel, The Practice on Writ of Trial For Debts Not Exceeding £20 Before the Sheriff (London: Sweet, 1833), p. xxiii. He seems to have been living in Marylebone in 1851. The bar seems to have had a fair number of Platts at this time, not least Thomas Platt, Baron of the Exchequer and his son, Charles, Associate of the South Eastern Circuit. Our man, however, seems not to be of this branch of the family: A. B. Schofield, Dictionary of Legal Biography 1845-1945 (London: Barry Rose, 1998), 362.

[2] Exeter Flying Post, 22 March 1849, p. 6.

[3] R v Latimer: Exeter Flying Post, 8 August 1850, p. 4.

[4] The Standard, 25 March 1850, p. 4.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

[…] Author bio: Richard W. Ireland has written extensively on the history of crime and punishment, including its representation in his other passion, visual art. A previous exploration of the connection between criminality and visual representation appeared in November 2023: On Delight in Legal History. […]

LikeLike