Guest post by Richard W. Ireland, 21 February 2024.

The London Female Penitentiary was an institution opened in 1807 at 166, Pentonville Road, London for “those females who, having deviated from the path of virtue, are desirous of being restored by religious instruction, and the formation of moral and industrious habits, to a respectable station in society.”[1] The purpose of this piece is to bring the existence of this institution, and of a couple of documents from my own archive which relate to it, to the attention of a wider readership; but also more generally to consider the nuances of the language used in the creation of our legal-historical narratives.

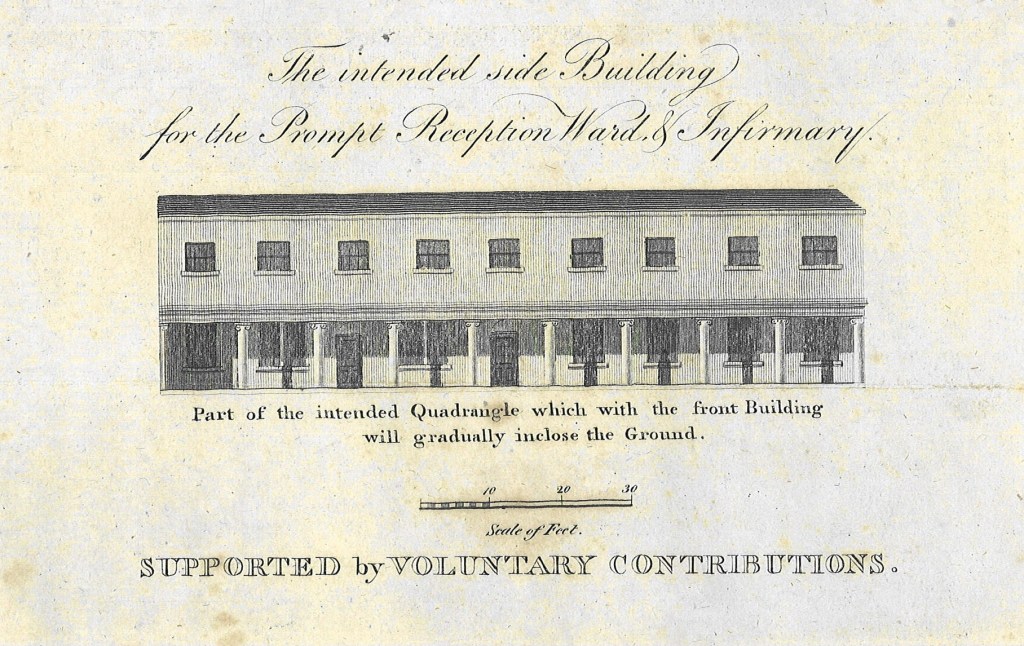

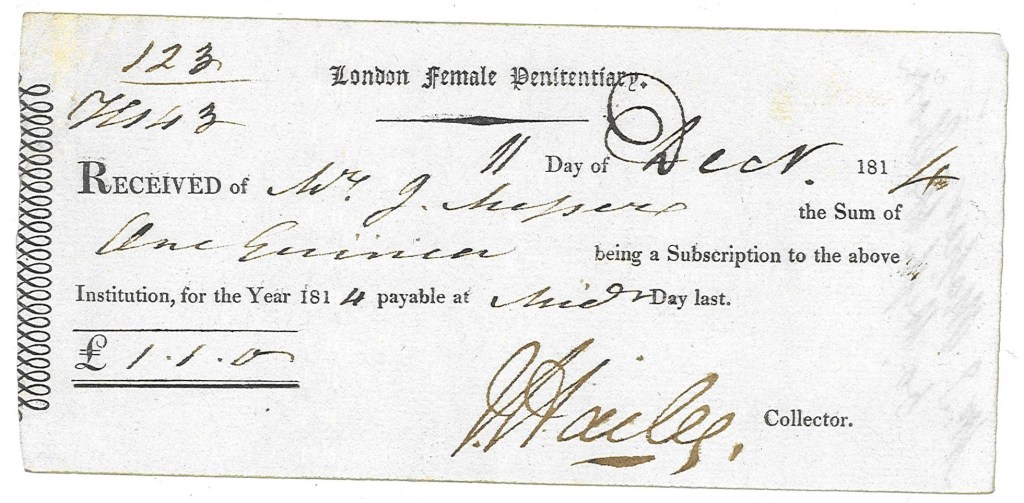

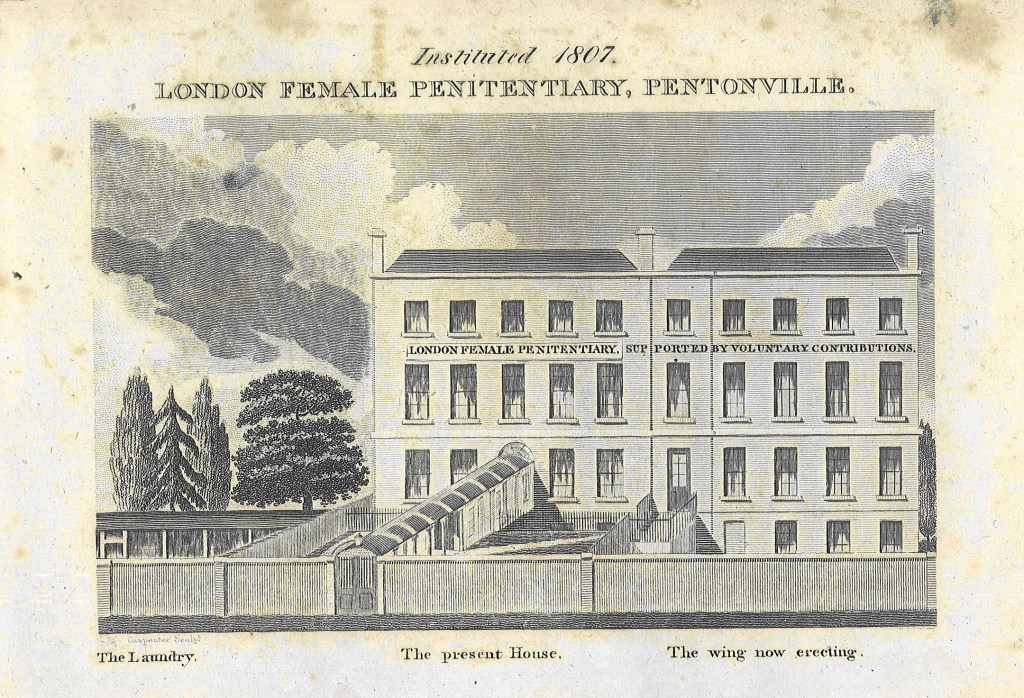

The institution, the inmates of which engaged in washing and needlework to inculcate such “industrious habits,” did not meet with universal approbation and provoked a vigorous and at times intemperate pamphlet exchange between supporters and opponents of the enterprise. Chief amongst the latter was William Hale, who argued that the existence of the Penitentiary would not only encourage the vice of prostitution but was in itself “a most fatal violation of the laws of God and man.”[2] Nonetheless the Penitentiary survived these attacks. It was funded by private subscription and a receipt issued in 1814 for a guinea towards that end survives (Figure 1). Indeed printed elevations from around 1811 show not only the existing building but also a new wing under construction and the intended reception ward and infirmary (Figure 2; see also the banner image). An article of 1848 reported that in the previous year subscriptions and donations to the institution amounted to £724, whilst the work done by the women produced £1184. There were, at that time, 100 inmates. Taken together with the other similar London institutions the total of eight housed 441 women at that time.[3] Other similar establishments existed outside London.[4]

While the history of the London Female Penitentiary deserves a much fuller treatment, I’d like to turn to the language used in discussing and reconstructing that history. To a modern reader the phrase “deviated from the path of virtue” in relation to the inmates of the institution smacks of euphemism. The pamphlets, on both sides, addressing the dispute more generally employ the term “prostitutes.” Yet I have long thought the meaning of this latter term, and particularly the nuances which it contains, when used in the nineteenth century may not correspond to our modern usage. Prostitution, and the modern term “sex work,” now indicate the transactional supply of sexual services in return for money. I am no expert on the nineteenth-century sex trade, and am conscious that others reading this piece may be, but it seems clear to me that those “straying from the path of virtue,” like their sisters described as having “lost their reputation” or “their name” could include a wider variety than the “streetwalkers,” “nymphs of the pavé” or “women of the town” who more accurately correspond to the stereotype of prostitution. If “loss of reputation” is a euphemism for anything then it is the loss of virginity outside marriage.

That this is the case for the administrators of the London Female Penitentiary is clear from the defence of the institution by Dobson who, whilst routinely employing the term “prostitutes” in relation to its inhabitants, states “I affirm as a fact that a full fourth part of the penitents, at present under the wing of the Penitentiary ARE seduced females who never have been on the town… Of these, there are several who have never had any criminal intercourse but with their seducers” [original italics].[5] It may be objected that this blurring of the edges of the term “prostitution” is merely a clumsy wording in relation to a specific institution, but I think not. Henry Mayhew writing in 1862 includes in his “classes of prostitution” the “kept mistresses” of gentlemen “of position” whose existence was known within society, as well as a more vaguely defined category of “prima donnas”, who apparently liked visiting parks and riding horses.[6] Mayhew was presumably not too concerned with the further specifics of their lives, for he states baldly “Literally every woman who yields to her passions and loses her virtue is a prostitute.”[7] But this broad usage was not, I think, restricted to middle class commentators. I was first alerted to the possible scattergun use of the term many years ago when researching the inmates of a local Welsh gaol, finding a woman, Anne Awberry, listed in a Police notebook as a “prostitute” at the age of 60. Awberry was many things, few of them “respectable,” but I am not convinced, and it is not simply her age which makes me say this, that sexual services were, at least at that time, intrinsic to her way of life.[8]

The other word which intrigues me in this context occurs in the institution’s title, namely “Penitentiary.” It is a word familiar to us today but, despite having medieval and ecclesiastical antecedents, it is relatively modern. The earliest English usage in the sense of a closed institution which I could find in the Oxford English Dictionary is from Bentham in 1776. It was soon to pass into wider circulation, however. The 1779 legislation which provided for two national “Penitentiary Houses” is generally referred to as The Penitentiary Act and is of central importance in British penal history, its s.5 laying down the aims (deterrence, reform) and methods (religion, solitude, labour), the combinations and recombinations of which were to be the main feature of prison philosophy and practice for the whole of the next century and beyond.[9] No such penitentiaries were built in the immediate aftermath of the Act, though provision of a part of Gloucester County Gaol for more serious offenders was given the name in 1791. But the London Female Penitentiary can perhaps claim to be the first discrete institution in the jurisdiction to which the name was exclusively applied.

This should not surprise us, for “fallen women” had, it was thought, their own inspirational model. The tradition which held that Mary Magdalene was a reformed prostitute had meant that the first refuge for such women in London, opened in 1758, had taken her name.[10] The first national “penitentiary”, for both sexes, was not opened until 1816 at Millbank. On 27 June 1816 the Professor of Music at Oxford, William Crotch, now perhaps more celebrated for his visual art, walked along the Thames and sketched the impressive mass of Millbank Penitentiary, which had the previous morning taken in its very first contingent of forty prisoners (Figure 3). Appropriately, perhaps, all were women.[11]

————

Author bio: Richard W. Ireland has written widely on the history of crime and punishment. Two of the books of which he is co-author, Imprisonment in England and Wales: a Concise History (with C. Harding, B. Hines and P. Rawlings) and Punishment: Rhetoric, Rule and Practice (with C. Harding) were reissued in 2023 by Routledge.

The banner image shows the intended reception ward and infirmary circa 1811. All archive material, and copyright in the reproductions, remain in the author.

Notes:

[1] Quoted in G. Hodson, Strictures On Mr Hale’s Reply To The Pamphlets Lately Published In Defence Of The London Female Penitentiary (London, 1809), 27. The quotation within my title is taken from the same source, p. 37.

[2] Ibid., 5. Hodson’s text quotes extensively from Hale’s pamphlets before robustly attacking his arguments. The volume also includes a letter from William Blair, Surgeon of the Penitentiary (and other organisations including the New Rupture Society!) on the inadequacies of the Poor Law as a protection for the inmates.

[3] Anon, review of A Short Account of the London Magdalene Hospital (1848), Quarterly Review 359 at pp. 361-362.

[4] Hodson, Strictures, p. 70 mentions Edinburgh, Bristol and Bath.

[5] Ibid., 47-48. I should perhaps make clear that pregnancy was not an issue in these cases: the condition barred entry into the Penitentiary.

[6] Henry Mayhew, London Labour and the London Poor, Volume 4. For ease I have used here P. Quennell’s text published as London’s Underworld (London, n.d.), see pp. 31-38.

[7] Ibid., 34.

[8] P.C. Williams’s Diary 1859-60, Carmarthenshire Archives Mus. 112. See the discussion in R. W. Ireland, A Want of Order and Good Discipline: Rules, Discretion and the Victorian Prison (Cardiff, 2007), 167-168.

[9] 19 Geo. III c.74.

[10] Magdalen Hospital (stgitehistory.org.uk) The spelling appears here as “Magdalen”, but is subsequently not consistent even in application to this institution, an uncertainty echoed in the names of Oxbridge colleges. The lamentable history of the “Magdalene laundries” in Ireland is still a scandal.

[11] See S. McConville, A History of English Prison Administration, Volume 1 (London, 1981), 136.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.