By Cassie Watson; posted 25 June 2024.

In July 2023 the Home Office and Department of Health and Social Care published a policy paper setting out a new “framework for how police and health services should improve the response to people with mental health needs.”[1] The impetus behind this initiative related largely to stresses on police resources: officers’ time was increasingly devoted to responding to “mental health issues which were more appropriately the responsibility of other agencies, and which reduced the time they could devote to their other tasks.”[2] This created negative consequences for both the patients and the police.

The Right Care, Right Person framework was therefore designed to assist “the police with decision-making about when they should be involved in responding to reported incidents involving people with mental health needs.”[3] Although the policy had already been successfully implemented in a number of local areas, the gap created when the police stepped back from intervening in mental health crises soon revealed dangerous shortcomings.[4] Without new funding for mental health services, these problems seem unlikely to be easily rectified.

However, there is no question that the police need to be involved in certain cases involving people suffering a mental health crisis, most obviously when there is a “real and immediate risk to life or serious harm, or where a crime or potential crime is involved.”[5] This post examines some of the historical situations that met these criteria, to consider how they were dealt with by police officers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

A Very Brief History of the Emergency Services

The emergency services in the United Kingdom comprise three main organisations: the Police Service, the Fire Service and the Emergency Medical Services.[6] While the latter is today the first port of call in a medical emergency, as a product of the National Health Service created in 1948 it is actually the junior emergency service. Its origins lie in the so-called casualty wards of the mid-nineteenth century hospital, to which accident victims or casual attenders were admitted.[7] The more numerous workhouse infirmaries could also receive accident patients,[8] but tended to be populated mainly by the chronic sick poor.[9]

Fire fighting, although highly localized, has a much longer history, but was placed on a modern professional footing more or less contemporaneously with the creation of the first uniformed police forces, in the early decades of the nineteenth century. The City of Glasgow Police was established in 1800, followed by London’s Metropolitan Police in 1829, while the first organised municipal fire brigade in the world formed in Edinburgh in 1824.[10] Only the police and fire brigade existed as nationwide institutions prior to the twentieth century, and their duties clearly overlapped where certain types of casualties were concerned.[11] Urban victims of physical injuries caused by street or workplace accidents were thus increasingly well catered for as nineteenth-century ambulance services developed,[12] but what emergency services were available to those suffering a mental health crisis?

Those who posed a danger to themselves or others could of course be committed to an asylum;[13] and there were special provisions and specific institutions designated for the criminally insane.[14] A significant body of scholarship addresses this group, but very little of it considers the role played by the police. However, it is clear from the modern practice of emergency psychiatry that police officers often bring patients in their custody for assessment, and may then become useful informants as a medical triage is performed.[15]

The Police and Psychiatric Emergencies

While policemen were duty-bound “to assist persons injured, or taken ill in the street,”[16] such duties had to be balanced with the needs of policing, namely crime control. This is nowhere more evident than in the pages of the Police Code, a handy manual written in 1881 by C. E. Howard Vincent (1849–1908), the first Director of Criminal Investigation in the Metropolitan Police. This book provided legal and practical advice to officers, to aid them in their daily duties, and was so successful that it had reached a sixteenth edition by 1924.

Relevant entries focused on physical assistance to the injured, offering quite detailed instructions on how to care for a casualty whilst ensuring that evidence was collected and the public was protected: accidents; corrosive fluid throwing; stretchers; treatment of persons rescued from drowning, hanging or suffocation; wounding. Alcoholic mania required both medical treatment and “severe handling and usual restraint.”[17]

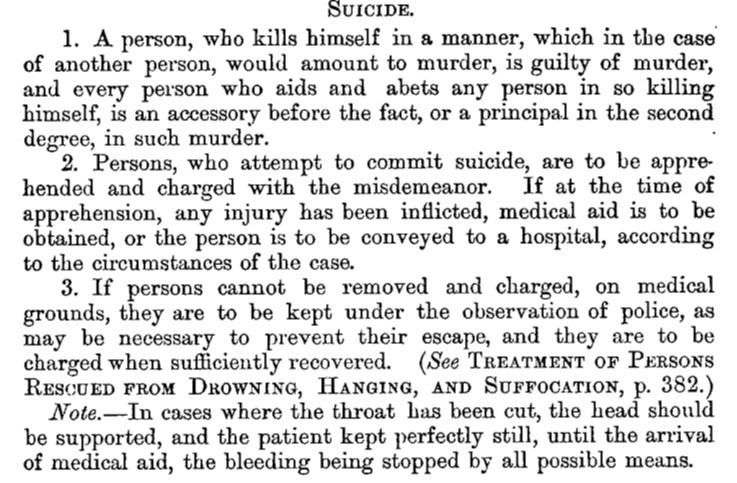

Three entries addressed scenarios that might involve a psychiatric emergency (insanity; lunatics; suicide), of which only the entry for suicide was not shortened in length for the eighth edition of 1893. A comparison of both editions — 1881 and 1893 — reveals a clear focus on the legal and physical rather than mental aspects of police encounters with suicidal or mentally distressed people. The entry for suicide gives a sense of this disparity:

While Vincent provided rules for deploying a stretcher and how to use it, there was no such detail with respect to mental illness. The 1881 entry for ‘insanity’ related mainly to the impact of criminal responsibility on trial proceedings (possible indefinite detention as a criminal lunatic), but that for 1893 was less than half the length and stated only the basic facts of the legal relationship between sanity and criminality.[18]

Only the entries for ‘lunatics’, which are among the longest in both editions, discussed actual encounters between police and mentally ill people. However, they bypassed the potential difficulties that might arise for patient or police, to focus instead on the duty of officers to apprehend alleged or escaped lunatics and convey them to an appropriate legal authority or institution.[19] How exactly they were to go about that, and with what amount of patience, sensitivity or discretion, was not stated.

Police Encounters with People in Mental Health Crisis

We can get some idea of how individual officers responded to potentially dangerous or criminal individuals suffering a mental health crisis from newspaper reports and legal records. A cursory search of The British Newspaper Archive reveals more than a few serving police officers who committed murder or other offences whilst suffering from alleged insanity,[20] as well as acts of bravery by police when apprehending perpetrators or rescuing victims.[21] That policemen may not always have recognised or acknowledged mental ill health is suggested by the opinion given by a Superintendent Minty to magistrates at Doncaster in 1930. When an alleged burglar was asked if he objected to being remanded, he declared that “I am Jesus Christ, and I am going to see the King,” to which Minty opined that “he was either acting funny or insane.” The man was remanded for a week and a medical examination ordered.[22]

It seems most likely that the police encountered mentally disturbed criminals in cases of infanticide and failed suicide pacts where one partner survived to face prosecution for murder. Doctors knew that melancholia was a possible precursor to suicide,[23] and that some women committed acts of violence when suffering from post-natal psychosis or depression.[24] Police officers cannot have been unaware of such associations, but as they were clearly expected to seek medical assistance, the details of what they were taught or actually knew require further investigation. Certainly they were alert to the possibility of a history of insanity when compiling what were known as antecedents reports, and they recorded behaviour observed at crime scenes or commented on the demeanour of alleged perpetrators; but only doctors could testify to mental health issues.

Finally, police officers might themselves fall victim to a mentally disordered offender, as for example when two officers were attacked and hospitalised by an insane German man at Southend in 1900.[25] However, when Thomas Abbott, a retired inspector with the City of London Police, was assaulted with vitriol by his wife Maria that same year, the suggestion that she was not responsible for her act — on the grounds of hysteria and the menopause — was rejected: she was sentenced to five years’ penal servitude.[26]

Conclusion

There were three main scenarios in which policemen encountered individuals in a psychiatric emergency. Least commonly, they became victims. More frequently, they were the colleagues of officers who became mentally unwell and committed a crime. Most commonly, the police were called to the scene of a crime where the alleged perpetrator was suspected or later found to be insane. Such cases were of interest to journalists seeking to report the actions of ‘plucky’ police, especially those who had saved a life or tackled a violent suspect. However, any opinions that the police themselves formed about the mentally ill were rarely reported: the law passed that responsibility to the medical profession and the courts.

It is a curious fact that the advent of the ‘new’ police made the systematic arrest and prosecution of some of society’s most mentally unwell people, those who attempted suicide, feasible,[27] while at the same time officers were expected to render aid to the injured — including those who had tried to kill themselves. This, then, was probably one of the most common ways in which the police came into contact with people suffering from a mental crisis, as there were far more attempted suicides than homicides in the UK.[28]

Images

Main image: Police ambulance entering mortuary. Source: George R. Sims, ed., Living London, vol. 1 (London: Cassell and Company, 1902), 311.

City of London police ambulance in 1913. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France. Wikimedia Commons.

References

[1] National Partnership Agreement: Right Care, Right Person, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-partnership-agreement-right-care-right-person#full-publication-update-history.

[2] Association of Police and Crime Commissioners, APCC Guidance: Right Care, Right Person and the National Partnership Agreement (April 2024), 4-5.

[3] National Partnership Agreement: Right Care, Right Person (RCRP), updated 17 April 2024.

[4] Rachel Hall, “Police in England must keep answering mental health calls, charity urges,” The Guardian, 24 March 2024.

[5] National Partnership Agreement: Right Care, Right Person (RCRP), updated 17 April 2024.

[6] D. Clark, “Emergency services in the United Kingdom – Statistics & Facts,” Statista, 20 December 2023 (accessed 12 June 2024).

[7] Henry Guly, A History of Accident and Emergency Medicine 1948-2004 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 2.

[8] Jonathan Reinarz and Leonard Schwarz, eds., Medicine and the Workhouse (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2013). See the chapters by Kevin Siena (p. 19) and Angela Negrine (pp. 202-203).

[9] On the chronic sick poor, see: Kim Price, Medical Negligence in Victorian Britain: The Crisis of Care under the English Poor Law, c.1834–1900 (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), chapter 6; and David R. Green, Pauper Capital: London and the Poor Law, 1790-1870 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010), 233, 237-239.

[10] Glasgow Police Act, 39 & 40 Geo III c. 88 (1800); Metropolitan Police Act, 10 Geo IV c.44 (1829). For a brief overview of the development of the three services, see Patrick Coleman, “In Search of Britain’s Oldest Emergency Services,” National Emergency Services Museum, 1 May 2020 (updated 11 June 2022; accessed 24 June 2024).

[11] Rebecca Wynter and Shane Ewen, “Choreographing Urban Ambulance in Britain, c.1870–1920: Movement, Gender, Biological Time and the City,” Social History 49, no. 1 (2024): 78-105. See also C. E. Howard Vincent, A Police Code, and Manual of the Criminal Law (London: Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co., 1881), 156-157.

[12] Wynter and Ewen, “Choreographing Urban Ambulance in Britain;” see also Matthew L. Newsom Kerr, “Perambulating fever nests of our London streets”: Cabs, Omnibuses, Ambulances, and Other ‘Pest-Vehicles’ in the Victorian Metropolis,” Journal of British Studies 49 (2010): 283-310.

[13] Joseph Melling, Bill Forsythe and Richard Adair, “Families, Communities and the Legal Regulation of Lunacy in Victorian England: Assessments of Crime, Violence and Welfare in Admissions to the Devon Asylum, 1845–1914,” in Outside the Walls of the Asylum: The History of Care in the Community 1750–2000, ed. Peter Bartlett and David Wright (London: The Athlone Press, 1999), 153-180.

[14] Katherine D. Watson, Forensic Medicine in Western Society: A History (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011), 84-90.

[15] Patrick Triplett and J. Raymond DePaulo, “Assessment and General Approach,” in Emergency Psychiatry, ed. Arjun Chanmugam, Patrick Triplett and Gabor Kelen (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 1-7.

[16] Vincent, Police Code, 243.

[17] C. E. Howard Vincent, The Police Code, and General Manual of the Criminal Law for the British Empire (London: Francis Edwards and Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., 1893), 67. All editions of the book were organised alphabetically by topic, most of which did not change much but were updated to take account of changes in the law and, presumably, evolving ideals of best practice.

[18] Vincent, Police Code, 202-203; Vincent, The Police Code, 97.

[19] Vincent, Police Code, 227-228; Vincent, The Police Code, 103.

[20] Liverpool Echo, 17 May 1886, 3; Bolton Evening News, 28 July 1905, 4; Belfast Telegraph, 17 December 1948, 5.

[21] Marylebone Mercury, 21 September 1901, 5; Dundee Evening Telegraph, 20 April 1932, 5; Faversham News, 27 August 1948, 4.

[22] Shields Daily News, 6 August 1930, 3.

[23] Olive Anderson, Suicide in Victorian and Edwardian England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 382-389.

[24] Hilary Marland, Dangerous Motherhood: Insanity and Childbirth in Victorian Britain (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004).

[25] Stockton Herald, South Durham and Cleveland Advertiser, 22 December 1900, 7.

[26] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 9.0) December 1900. Trial of Maria Abbott (47) (t19001210-74). Available at: https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/record/t19001210-74?text=maria%20abbott (accessed: 25th June 2024).

[27] Anderson, Suicide in Victorian and Edwardian England, 282-290.

[28] Hampshire Telegraph, 9 February 1907, 11. This article states that 3,345 people took their own lives in England and Wales in 1904 and estimates that a similar number were prevented from doing so. The official judicial statistics for the same year record a total of 3,327 inquest verdicts of suicide and 317 of culpable homicide: Judicial Statistics, England and Wales, 1904: Part 1, Criminal Statistics (London: HMSO, 1906), 20.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.