Posted by Krista Kesselring and Emily Martens-Oberwelland, 22 July 2024.

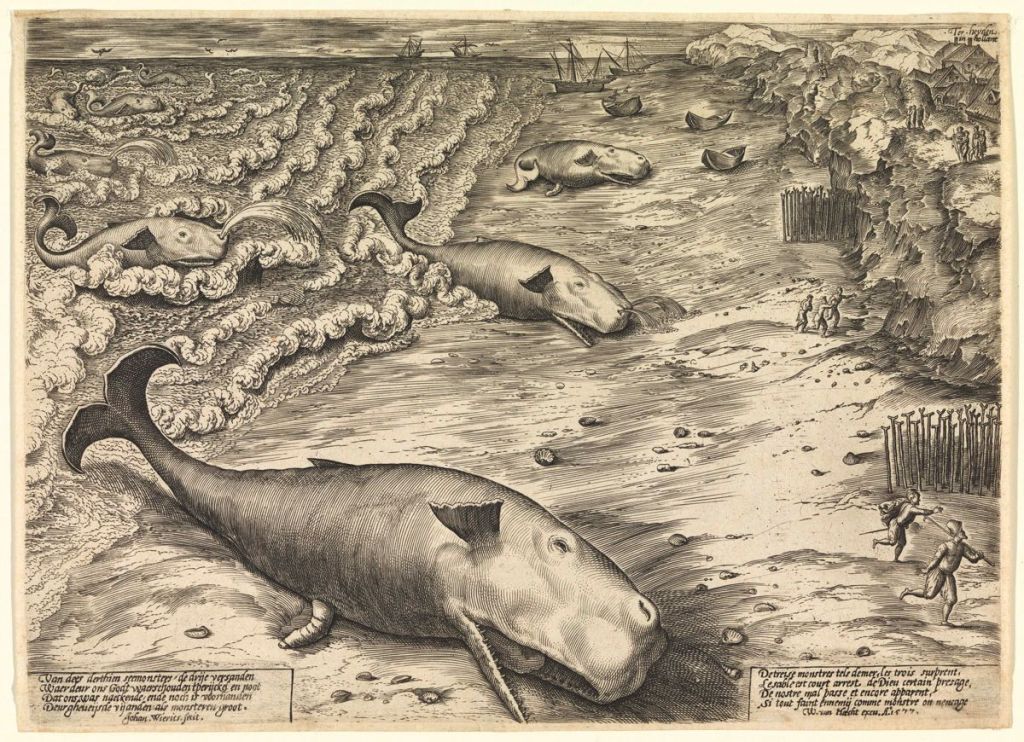

The past month has produced several sad accounts of whales stranded on shores around the globe. Seventy-seven pilot whales beached in Orkney. A rare spade-toothed whale washed up on the coast of New Zealand. Here in Nova Scotia, a humpback whale—one of the largest and most magnificent of all creatures—died after swimming too far up the Stewiacke River and getting stuck in a sandbank. Such strandings now provoke reactions that range from curiosity to concern – concern about how to dispose of the bodies safely and perhaps above all, concern that the effects of climate change or seaborne traffic are making them likelier. Injuries from ship strikes and entanglement in fishing gear, confusion arising from noise pollution, and changes to their food supplies caused by rising water temperatures may well be making these losses more common, or at least more often the fault of human action, but some such strandings have always occurred. In medieval and early modern England, they also provoked a good deal of curiosity and concern – though a concern primarily for profit and competing rights-claims. For all the changes over time in human/whale encounters on the foreshore and at sea, one thing remains the same: whales then, as now, are the preeminent creatures in a category English and Welsh law treats as ‘royal fish’. But before the era of petroleum and plastics, and as seaborne trade expanded, whales found ashore became focal points for social and legal contention as people sought to make them ‘matter’ in a range of ways both old and new.

A Fish Called Royal

Today we classify whales as mammals—like humans, apes, and elephants—but pre-modern observers unsurprisingly deemed these denizens of the deep to be ‘fish’. Somewhat more surprisingly, many writers also deemed them to be royal fish when found on or near the coast, a classification that included sturgeons and sometimes porpoises, dolphins, and ‘grampus’, a name used for a variety of ‘fish of extraordinary greatness’.[1] As royal fish, they all belonged to the Crown—if the Crown’s agents worked fast enough.

The Crown’s claim to whales was remarkably long-lived, though its contours and justifications changed over time. It may have had pre-Conquest roots, with similar assertions made by Norman, Danish, French, and Scottish lords (among others). It received an early mention in Henry de Bracton’s thirteenth-century legal text: wild animals generally belonged to no one, but whales that came ashore became the king’s, though ‘it suffices, according to some, if the king has the head and the queen the tail’.[2] The claim received a more expansive statement in the fourteenth-century Prerogativa Regis, which declared that the king shall have ‘wreck of the sea throughout the realm, [and] whales and great sturgeons taken in the sea or elsewhere within the realm, except in certain places privileged by the king.’[3] Edmund Plowden wrote in the sixteenth century that the Prerogativa Regis merely restated a pre-existing common-law right, a right held by the Crown simply because whales and sturgeons ‘are the most excellent fishes that the sea or water renders’.[4] Writing in the mid-eighteenth century, William Blackstone similarly observed that whales found ashore or caught near the coasts belonged to the king ‘on account of their superior excellence’ – though he also suggested that the sovereign’s right to the revenue derived from whales was ‘grounded on the consideration of his guarding and protecting the seas from pirates and robbers’.[5]

The claim’s tangible benefits shifted over time, too. When Prerogativa Regis was first drafted, the kings of England also had lordship over territory on the French Biscayan coast, an area where right whales abounded until overhunted or frightened away by the Basques’ precocious commercial whale fishery. [6] Maybe there the claim to whales offered a more routinely reliable source of income than in England itself, where its benefits arose only haphazardly when whales ran aground. Very often, medieval kings opted to benefit from the claim by granting the rights to wreck of the sea and to royal fish to manorial lords as tokens of favour and reward.[7] Over the sixteenth century, the Crown delegated its own claims to the Lord Admiral and Vice Admirals for collection, as a source of patronage for office holders and a cost-effective way to keep royal claims alive.[8] Admiralty officials could be counted on to harass and haggle with manorial lords who tried to profit from strandings. Both worked to stymie the efforts of locals who were often first to the shore to try to reap the unexpected bounty of the sea.

Making Whales Matter

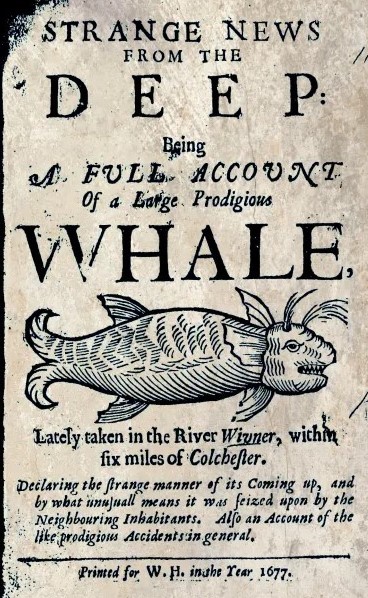

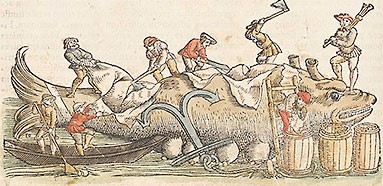

When whales came aground, people reacted with a mix of curiosity, wonder, fear, and pragmatic self-interest. Some people interpreted them as signs or portents. The beaching of a prodigiously large whale at Dover shortly before the execution of King Charles I was widely commented upon, for example, especially after another stranding presaged the death of Oliver Cromwell.[9] But another common response was to see a whale ashore simply as good fortune, to grab the knives and buckets for flensing the unfortunate creature, and to try to turn it to the benefit of those who found it. Among other uses, a whale’s enormous tongue could be eaten; any baleen (‘whalebone’) could be shaped to stiffen women’s clothing and to make some of the things for which we turn to plastics today; and its blubber could be boiled to make the highly valued oil (called train oil, from the Dutch ‘traan’, for tears) that went into such things as soaps, lamps, and lubricants.[10]

Agents of local lords and Admiralty officials worked quickly to claim these prizes for themselves but sometimes became embroiled in protracted disputes in the courts. On 21 November 1600, for example, tenants of Sir Nathaniel Bacon went to his bailiff to report that a great fish, possibly a porpoise, had washed ashore in (or on the boundary line of) Bacon’s manor of Hemsby, near Yarmouth. The bailiff and a jury of six local men showed up with a rope and stake to claim the creature, purportedly for both the queen and their lord; but the marshal of the Admiralty court showed up, too, claiming it for the queen and admiral. A lengthy dispute ensued, with the bailiff and the man who bought the creature both hauled into an Admiralty court ‘to undergo the law’. One assessment valued the animal at ‘at least’ £10, but even more than the immediate gain to be had from the find, what seemed to matter most to Bacon and to the Admiralty officials was asserting their respective rights to goods found on that stretch of shore. Correspondence on the matter continued through to at least June of 1601.[11]

In December 1601, a whale said to measure some 17 yards in length came ashore in Croft manor, near Skegness. Sir Valentine Brown, the manorial lord, sent two of his servants to guard the ‘fish royal’ until he could find workmen to fetch it away, but Admiralty men also showed up to mark it as theirs. Brown’s workers cut up the whale and carried off the pieces nonetheless, with Brown claiming it as his because he had the right to wrecks on his shores; the Admiralty officials claimed it to their use and the queen’s by royal patent, insisting that a manorial grant of rights to wrecks did not extend to royal fish. After arrests and appearances in the local Admiralty court, Brown took the dispute to the Court of Star Chamber in May 1602.[12] Quite how the matter ended isn’t clear, but the ‘royal fish’ themselves and the rights they represented clearly had value worth contesting.

A particularly well recorded dispute over a great baleen whale blown ashore in a gale began on 16 December 1647 (in a civil war context in which the ‘royal’ epithet seems to have been studiously avoided). ‘There is this day a whale cast ashore’, wrote Richard Edgcumbe from Mevagissey, Cornwall to his brother Pears, the manorial lord. As soon as he heard of the stranding, Richard and a local Justice of the Peace hurried to the corpse and ‘put the country people from it, after their carrying away much thereof’. He claimed the remnants for Pears but unsure of what to do with the immense carcass, he called upon a Plymouth pilchard merchant who had previously seen whales butchered by the Basques. ‘Joining our best wits together, we fell to work there to cut out the tongue.’ Leaving a watch, they came back the next day to tow the rest away, ‘to convert into oil’. Described as being 72 feet in length and some 30 feet around, the whale had dark blue skin and ‘under his belly was laced from the mouth to the navel with white and gray, like the sides of a ship’. Richard expected at least two tons of train oil from this ‘great wonder lately come ashore’. With undue early optimism, he reported to Pears that the work on this whale ‘will fully strengthen your title forever hereafter’. But the Vice Admiral soon arrived to question Edgcumbe’s claim to the whale: ‘a servant to the state hearing of this thing, he came to seize it to their use’. By February 1647/8, the ‘Committee of Lords and Commons’ who then ran the Admiralty decided that they were owed the proceeds of the sale of the whale oil, noting in a letter that they expected payment within 15 days or the men would be called into the central Admiralty court. In the end, it seems that the Admiralty’s claim succeeded.[13]

One striking aspect of these accounts is that the lords and officials who contended for control of the whales focused not just on the profits to be had after they ‘converted the same into oil’ but perhaps even more so on the competing rights-claims at stake. Entitlements to the flotsam, jetsam, and shipwrecks found on or near the shore needed to be defended, given their potential value. Whatever worth the ‘country people’ who descended upon a whale carcass thought it might have for themselves, landlords and Admiralty men sought control to prop up other, larger claims. In this they were joined by the Crown (or State) itself.

Sixteenth and seventeenth-century writers repurposed ancient claims to ‘royal fish’ to assert royal rights to the foreshore and adjacent seabed. The polymath and projector Thomas Digges penned a tract in 1569 that adduced this medieval prerogative as one of the ‘arguments proving the Queen’s Majesty’s property in the sea lands and salt shores thereof, and that no subject can lawfully hold any part thereof but by the king’s special grant’. Digges rather creatively (and to his own benefit) asserted that the kings (and queens) of England ‘always reserved to themselves the chief fish as sturgeon, whale, &c.’ precisely to ensure that ‘the memory of their property in the seas should not be extinguished’. Writers such as Robert Callis, William Welwood, John Burroughs, John Selden and others later cited the same evidence for expansive claims to the foreshore, even as sovereignty over ‘open’ or ‘closed’ seas became contested more broadly. Claims to the high seas proved contentious with the Dutch and others; claims to the land between the high and low water marks proved contentious with lords at home, being cited amongst other grievances in the Grand Remonstrance that preceded the Civil War.[14]

David Cressy has recently described shipwrecks as ‘social dramas at the juncture of land and seas’.[15] Much the same can clearly be said of whales washed ashore. The people who found them on the coasts of early modern England sought to turn them into consumable, saleable matter; to landlords and Crown agents the whales also mattered as markers of rights-claims. While they remain ‘royal fish’ in English and Welsh law even today, the Receiver of Wreck now assumes responsibility for stranded cetaceans with an eye to safe disposal and scientific analysis.[16] The royal right to much of the foreshore remains, too, and may actually be more valuable than ever before: it now brings in vast revenues through leases for offshore windfarms, for example. It may thus also allow the better development of ‘seabed assets’ in ways that promote renewable energy and help meet climate targets. If pursued with care, that much, at least, would be an interesting legacy for the creative rights-claims built over centuries on the backs of these wondrous fellow-creatures, ‘royal’ or not.[17]

Guest co-author bio: Emily Martens-Oberwelland completed a Combined Honours BSc in Marine Biology and History at Dalhousie University. She is now working on a Master of Arts thesis at Dalhousie on the history of encounters with whales in early modern England. She is also completing the International Master of Science in Marine Biological Resources (IMBRSea), an Erasmus Mundus programme organized by a consortium of European universities.

Images:

Cover image and no. 2, above, ‘The Whale Beached between Scheveningen and Katwijk’ by Esaias van de Velde, 1617, via Wikimedia Commons.

Illustration of whale flensing from Konrad Gesner, Fischbuch, 1598, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image 117 from Adriaen Coenen’s ‘Vis Booc’ (Fish Book), 1577-79, courtesy of the World Digital Library/Library of Congress.

Three Beached Whales, print by Johannes Wierix, 1577, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image from Joachim Camerarius, Symbola et Emblemata (1590-1604).

Notes:

[1] Quote from William Welwood, An Abridgement of All Sea Laws (London, 1636), p. 43. For more background, see Cyrus H. Karraker, ‘Royal Fish’, The Quarterly Review 529 (July 1936), 129-37 and Dan Brayton, Shakespeare’s Ocean: An Ecocritical Exploration (Charlottesville, 2012), ch. 5.

[2] Henry de Bracton, On the Laws and Customs of England, ed. and trans. Samuel E. Thorne, vol. 2, pp. 339-40, via Bracton Online. The notion that the head belonged to the king and the tail to the queen reappeared in William Prynne, Aurum Reginae (London, 1668), p. 127, who suggested that Queens Anne and Henrietta Maria, the wives of James I and Charles I, resumed such claims to get whalebone for their clothing (though ‘whalebone’, or baleen, would have come from the heads, and only the heads of one subset of whales). The notion that the queen got the tail is perhaps best known because it appeared in Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick.

[3] Prerogativa Regis, temp. uncertain, Statutes of the Realm, ed. A. Luders et al (London, 1810-28), v. 1, p. 226

[4] Edmund Plowden (1518-1585), An Exact Abridgment in English of the Commentaries or Reports of the Learned and Famous Lawyer, Edmond Plowden (London, 1650), p. 315.

[5] William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England (Oxford, 1765-9), Book 1, c. 8.

[6] The Gascon connection is suggested in Richard Ellis, Men and Whales (New York, 1991), p. 45. On medieval whaling, see esp. Vicki Ellen Szabo, Monstrous Fishes and the Mead Dark Sea (Leiden, 2008).

[7] See Tom Johnson’s ‘Medieval Law and Materiality: Shipwrecks, Finders, and Property on the Suffolk Coast, ca. 1380-1410’, American Historical Review 120.2 (2015), 407-432 and ‘The Economics of Shipwreck in Late Medieval Suffolk’, in Custom and Commercialization in Rural England, c.1350-1750: Revisiting Postan and Tawney, ed. Alex Brown and James Bowen (University of Hertfordshire Press, 2016), pp. 121-38.

[8] Johnson, ‘Medieval Law’, 430, citing Reginald G. Marsden, Select Pleas in the Court of Admiralty (Selden Society, 1894), pp. xi-lxxxviii; see also 5 Elizabeth I, c. 5, An Act Touching Certain Politique Constitutions Made for the Maintenance of the Navy, and the various published Admiralty articles of inquiry, e.g., Articles Concerning the Admiralty of England (London, 1591), item 9.

[9] Anon., Strange Newes for England: Being a True and Perfect Relation of the Two Great and Unheard of Wonders Seen in the River of Thames (London, 1659), pp. 3-6. On such prodigies, portents, and providential readings of unusual natural phenomena, see, e.g, Alexandra Walsham, ‘Vox Piscis: or, The Book-Fish: Providence and the Uses of the Reformation Past in Caroline Cambridge’, English Historical Review 114 (1999), 574-606: studying a different ‘piscatorial prodigy,’ Walsham notes that many Protestants, while disdaining ‘miracles’ as superstitious nonetheless regarded the natural world as a ‘hieroglyph of celestial wisdom’ that showed the hand of God, alongside assumptions that ‘the physical environment was morally sensitive and responsive to human fortunes and transgressions, a mirror and cipher of the spiritual sphere’ (577). For an illustrated introduction to prodigy pamphlets focused specifically on whales, see the blog post ‘Wondrous Whales’, Streets of Salem, 12 June 2013.

[10] For more on the uses of whales, see, e.g., William Scoresby, An Account of the Arctic Regions: with a History and Description of the Northern Whale-Fishery (Edinburgh, 1820), II. 420-43. On baleen, see Sarah A. Bendall, ‘Whalebone and the Wardrobe of Elizabeth I: Whaling and the Making of Aristocratic Fashions in Sixteenth-Century Europe’, Apparence(s): Histoire et Culture du Paraître 11 (2022).

[11] The Official Papers of Sir Nathaniel Bacon of Stiffkey, Norfolk, as Justice of the Peace, 1580-1620, ed. H.W. Bacon Saunders (London, 1915), pp. 201-16.

[12] The National Archives (Kew), STAC 5/B2313; Lincolnshire Record Office, TYR 2/1/53a. A note in TYR 2/1/53 details the profit made from a whale found in Croft, but possibly another, later stranding of a smaller whale. It includes the pay for labourers who cut the whale in pieces, as well as the costs of the tubs and barrels needed to boil down the blubber and to carry the oil, with the oil sold for £8 15s, clearing £4 after expenses.

[13] Kresen Kernow (formerly the Cornwall Record Office), ME/2819-2822, 2824, 2825, 2828. Though Richard later reported having produced only four hogshead of oil (one ton) from the whale; maybe his early estimates shared with his brother were overly optimistic, or maybe they did at least retain some profit from the find.

Compare Edgecumbe’s description to that of a ‘great and monstrous fish’—said to be 23 yards long and 26 feet around— that stranded on the Goxhill shore near Skitter Ness on 21 October 1604: ‘Her belly was white and pleated like to the pleat of a mattress, every pleat about ten inches broad’. Interestingly, this observer also noted the whale’s warm-bloodedness: before she died ‘she was as hot upon the outside as any horse is when he is sore ridden’. Lincolnshire Record Office, Cragg/2/4, f. 1, printed in Lincolnshire Notes and Queries 18 (1924-5), pp. 31-2.

[14] Thomas Wemyss Fulton, The Sovereignty of the Sea (London, 1911), pp. 362-6 and Stuart Archibald Moore, A History of the Foreshore and the Law Relating Thereto (London, 1888), pp. 172, 177, 203, 256, 310. Moore reprints Digges’s tract from the copy in British Library, Lansdowne MS 100 and notes that an earlier copy with notations in William Cecil’s hand can be found in Lansdowne MS 105. John Gibson has critiqued Digges’s self-interested and suspect reworking of historical precedent as well as the very concept of the foreshore in a number of publications, including ‘Foreshore: A Concept Built on Sand’, Journal of Planning and Environmental Law (1977), 762-70.

[15] David Cressy, Shipwrecks and the Bounty of the Sea (Oxford, 2022), quote at p. 14. Many works recount Anglo-Dutch rivalry, and the writings of Hugo Grotius and John Selden advocating open and closed seas respectively, but for an introduction focused specifically on the nascent Spitzbergen whale fishery, see Dagomar Degroot, ‘War of the Whales: Climate Change, Weather and Arctic Conflict in the Early Seventeenth Century’, Environment and History 26.4 (2020), 549-77.

[16] In Scotland, ‘royal fish’ only included those ‘too large to be drawn to land by a “wain pulled by six oxen”’, now interpreted to mean whales that measure more than 25 feet in length. (As such, the pilot whales recently stranded in Orkney may not have been covered.)

[17] Of course, offshore windfarms might pose their own hazards to whales, though scientific consensus seems to suggest otherwise, on balance, so long as care is taken in the loud construction phase. See, e.g., this report by Alison Pearce Stevens from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, 9 May 2024.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.