By Cassie Watson; posted 27 September 2024.

In 2023 a four-part documentary series re-examined the murders of four Dallas-based flight attendants and asked — on the strength of new discoveries, including DNA evidence — whether the wrong man has been imprisoned for one of them.[1] The victims were killed between 1978 and 1984 and Jonathan Reed, now 72, was convicted and sentenced to death for the first murder. He has since had two retrials, both of which, despite new evidence, ended in conviction. Although his death sentence has been overturned, he is currently serving life in prison — even though DNA testing has shown that he was not the source of semen recovered from the victim,[2] and there is no physical evidence to tie him to the crime. According to the documentary, his most recent conviction (in 2011) rested largely on the testimony of two eyewitnesses, whom jurors found particularly convincing. What is especially interesting about this, and what links this case (albeit rather tenuously) to my current research on the crimes of Jack the Ripper, is the fact that Reed does not match the main eyewitness’s description especially closely and has a sound alibi. Rightly or wrongly, the documentary gives the impression that the jury convicted him because they found the eyewitnesses to be more credible than the alibi or scientific evidence.

The Reliability of Eyewitness Identification

Eyewitnesses play an important role in criminal cases when they can identify culprits, but research has demonstrated that “Prior experiences are capable of biasing the visual perceptual experience and reinforcing an individual’s conception of what was seen.”[3] “As time passes, memories become less stable. In addition, suggestion and the exposure to new information may influence and distort what the individual believes she or he has seen.”[4] However, psychologists have recently argued that misidentifications should not be blamed on the unreliability of eyewitness memory, but on faulty legal processes after the initial eyewitness description was given. Thus, in the immediate aftermath of an event, the identifications made by witnesses who are sure of what they have seen are likely to be highly accurate.[5] In other words, “when properly tested the first time, eyewitness memory is reliable in that confidence is highly predictive of accuracy, with high confidence memories often being impressively accurate.”[6]

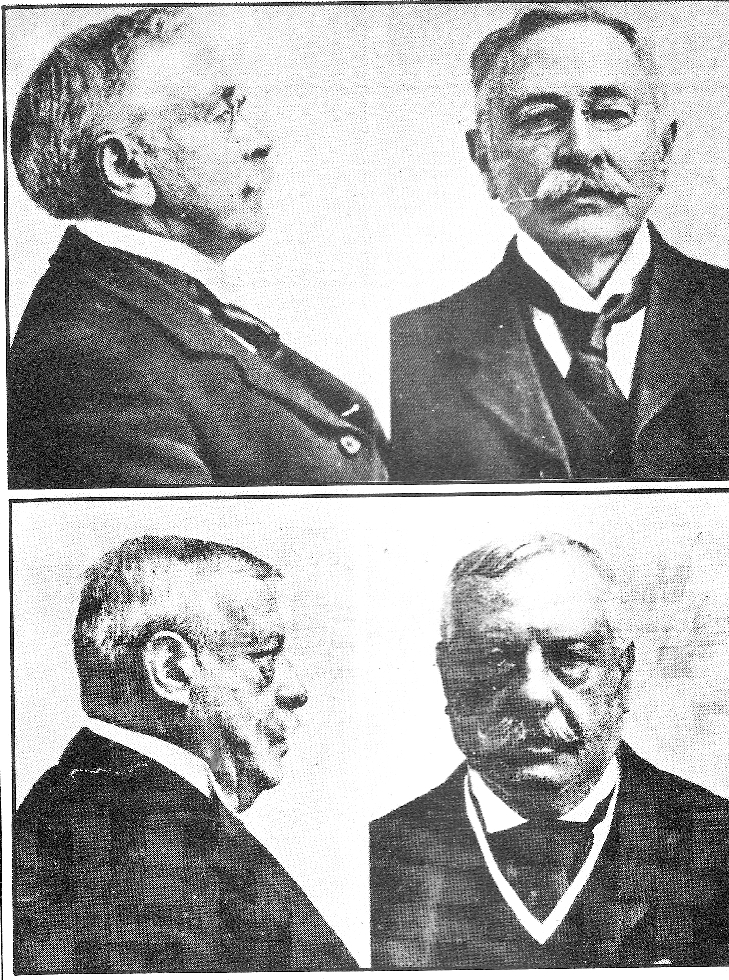

This scientific literature tends to focus on identifications made of suspects in custody, where of course all manner of potential bias might creep in, consciously or not.[7] One of the most infamous historical examples of a miscarriage of justice effected in this way is the case of the unfortunate Adolf Beck (1841-1909), who was twice convicted as a result of mistaken identity and eventually received £5,000 compensation for his imprisonment based on faulty witness identification.[8] But the scholarship on identification could also suggest that greater attention should be focused on the descriptions that eyewitnesses to or victims of crime are able to give in the minutes or hours, rather than days or weeks, following the incident. Yet, historic examples show that even this may not be as clear-cut as we might wish.

The Shooting of Ann Houghton, 1801

“If it was the last breath I had to draw, and I never was to enter the kingdom of heaven, that is the man that fired at me, and no living soul saw it besides myself.” So declared Ann Houghton, the victim of a random shooting on 6 October 1801, at the trial of her alleged attacker three months later. She testified with the conviction of one who had survived being shot in the face: it was light enough to see, and she had recognised the man, whom she knew by sight, as he passed her. Thus, Houghton was adamant that the perpetrator was one William Pearce, alias Benton. The problem for her case, however, was that someone else had seen the encounter, and stated that the shooter was most definitely not Benton. When Benton “proved an alibi, and likewise evidence to shew that a person of a different description had fired the pistol,” he was acquitted.[9] How could Ann Houghton have misidentified her attacker? By contrast, if another eyewitness had not come forward, would Benton have been convicted?

It seems that Benton was arrested fairly quickly after the shooting, as he was examined for a third time at the Hatton Garden police office on 12 October. This suggests that, despite her injuries, Houghton was able to identify him soon after the shooting. He had been part of an excited crowd that gathered to view the first night of the illuminations displayed in London after the preliminary terms of the Treaty of Amiens were agreed and signed on 1 October 1801. The fact that there had been a mob was part of the problem: there were lots of possible witnesses but few had paid attention to the victim as she sat on her doorstep; and even though Benton was the main suspect, the press reported that the perpetrator may have been “some other man.”[10] Benton’s clothing was to play a significant role in establishing that he was not the shooter: a neighbour standing within 5½ yards of Houghton and 3 yards of the perpetrator was able to describe the latter’s attire, and it did not match what Benton was said to have been wearing that evening.

In his study of the identification of the unknown dead in England and Wales, Fraser Joyce found that clothing was as important an identifying characteristic as a physical description.[11] The dead might not be recognised by their friends if they were wearing something unexpected, or nothing at all: “investigators acknowledged that dress contained a great deal of information about the wearer and demonstrated that individuals were marked out from one another by its distinctive, individualistic characteristics.”[12]

This offers a possible explanation for the discrepancy between Ann Houghton’s eyewitness testimony and that of her neighbour. Modern psychological studies predict that Houghton’s identification was likely to be highly accurate, despite the stress she undoubtedly felt in the moment the gun was pointed at her.[13] But if Benton was wearing something that his acquaintances did not associate with him, it is possible that he was not recognised by the neighbour.

Eyewitness Evidence in the Case of Jack the Ripper

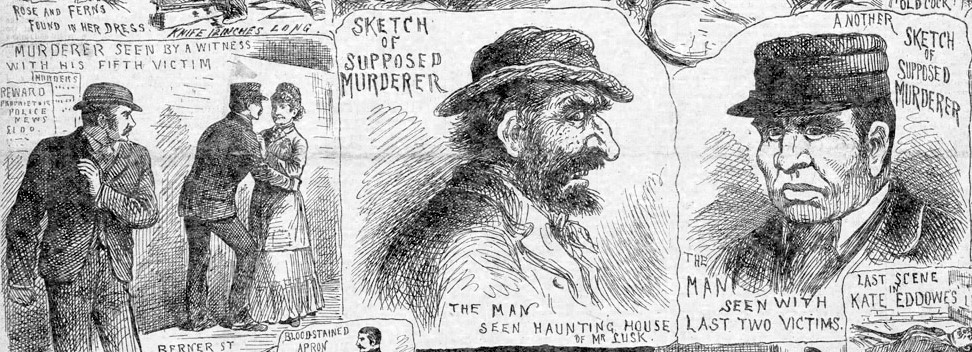

It is therefore unsurprising that the eyewitnesses who may have seen the killer known as Jack the Ripper in the autumn of 1888 tended to focus on what the man was wearing. By late October the press had published three different sketches of men thought to be the “supposed murderer,” based on the evidence given by various witnesses who had seen the victims with men shortly before they were found murdered. One example will suffice.

The image on the left reflects the testimony of Joseph Lawende, a commercial traveller, who saw a woman who may have been Catherine Eddowes with a man very shortly before she was found dead in Mitre Square on 30 September 1888. He was able to describe the clothes of both individuals, and the man’s general appearance, but thought he would not be able to recognise him again.[14] If Eddowes was the woman Lawende saw, then it is reasonable to believe that her companion was probably Jack the Ripper;[15] but the evidence that it was her was by no means solid, as Lawende saw her only from the back and relied on the similarity between her clothing and that of the woman he saw.[16] Dozens of local women may have owned similar clothing, a black jacket and a black bonnet, but there is no evidence to suggest the police made an effort to find out.

The central image reflects the growing sense of hysteria that emerged as the killings continued. It depicts a mysterious man who attempted to speak to George Lusk, the chairman of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, at a pub near his home in early October. While the man’s behaviour was undoubtedly suspicious,[17] there is no evidence to suggest that he was the killer. The Ripper case shows that eyewitness identifications can hinder investigations, as well as help them.

Conclusion

Eyewitness identification was and remains a key aspect of the prosecution process, and has thus rightly been the subject of a growing number of academic studies designed to identify the best practices to be used during investigations and in court. These findings seem to offer some useful insights to criminal justice historians seeking to understand past prosecution and conviction rates.

Images

Main image: Identification Parade, 1887. A fearless little girl picks out a man in an identification parade. Illustration by Renouard in The Graphic. Credit © Illustrated London News Ltd/Mary Evans.

Police mugshots of Adolf Beck (top), wrongly convicted for the crimes of William Meyer (bottom), circa 1907. Source: scan from “Crimes and Punishment” magazine, Wikimedia Commons.

The Illustrated Police News, 20 October 1888, 1. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

References

[1] The Flight Attendant Murders, Flicker Productions, 2023.

[2] John Seasly, “Jonathan Bruce Reed: Ironclad alibi did not avert death sentence,” Injustice Watch, 25 November 2019.

[3] National Research Council (U.S.), Committee on Scientific Approaches to Understanding and Maximizing the Validity and Reliability of Eyewitness Identification in Law Enforcement and the Courts, Identifying the Culprit: Assessing Eyewitness Identification (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2015), 1.

[4] Ibid., 15.

[5] John T. Wixted and Laura Mickes, “Eyewitness memory is reliable, but the criminal justice system is not,” Memory 30, no. 1 (2022): 67-72.

[6] Ibid., 68.

[7] The police have long been aware of this: C. E. Howard Vincent, A Police Code, and Manual of the Criminal Law (London: Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co., 1881), 185.

[8] The Strange Story of Adolph Beck (London: The Stationery Office, 1999); Dundee Evening Telegraph, 8 December 1909, 5.

[9] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 9.0) January 1802. Trial of William Pearce, alias Benton (t18020113-1) (accessed 25 September 2024); The Oracle and the Daily Advertiser, 14 January 1802, 2.

[10] General Evening Post, 17 October 1801, 1.

[11] Fraser Joyce, “Naming the Dead: The Identification of the Unknown Body in England and Wales, 1800-1934,” PhD thesis, Oxford Brookes University, 2012.

[12] Ibid., 210-218 (quotation is on p.218).

[13] Wixted and Mickes, “Eyewitness memory is reliable,” 71.

[14] Illustrated Police News, 20 October 1888, 2.

[15] Stewart P. Evans and Keith Skinner, The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook (London: Robinson, 2001), 138.

[16] Ibid., 207.

[17] Ibid., 275-276.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.