Guest post by Richard W. Ireland, 6 December 2024.

For an artist who can be (literally) viscerally direct, William Hogarth is capable of considerable subtlety. In his engravings on the subject of crime and punishment, a matter of considerable interest to him, Hogarth is capable of concealing a second, more critical narrative behind the obvious one readily accessible to the viewer. This can be seen in his wonderful series of engravings Industry and Idleness of 1747, in which the progress of the “industrious apprentice” Goodchild to the position of Lord Mayor is contrasted with the alternate scenes of his fellow apprentice Tom Idle, whose career follows a pattern familiar from eighteenth-century narratives of criminality — gambling, taking up with prostitutes, resort to crime and inevitable execution. It should, I think, now be accepted that the story can be read in a very different way if the pictures are looked at more closely, to reveal that both Goodchild’s ascent and Idle’s demise may both be seen as tainted by injustice.[1]

It’s another of his narrative collections, the famous Four Stages of Cruelty of 1751, that I want to consider here. I profess no outstanding expertise in Hogarth’s work, but I can at least claim familiarity with these pictures, for I pass them on the stairs every day when I am at home. In the years since I have had the pictures (etching and engravings) I have had cause to think hard about some of the elements in them which I have not found addressed in the literature I have consulted.[2] I’ll take you through an initial description of the series, though many readers may know it, and in particular the much-reproduced fourth plate. Then we’ll go back and have another, rather less superficial, look.

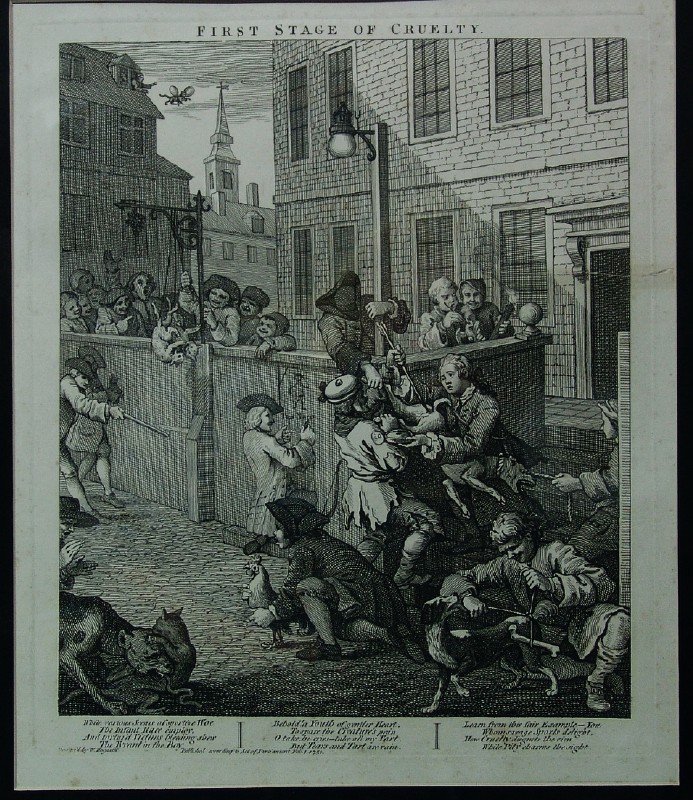

The First Stage Of Cruelty (Fig. 1) introduces our main protagonist, Tom Nero, whose badge shows him to be in the care of the parish of St Giles. Nero is at the centre of a scene of horrendous cruelty towards animals, cruelty both perpetrated by and encouraged by children. Nero is so intent on the egregious torture of a dog that not even the entreaties of a well-dressed youth offering a pie can dissuade him.

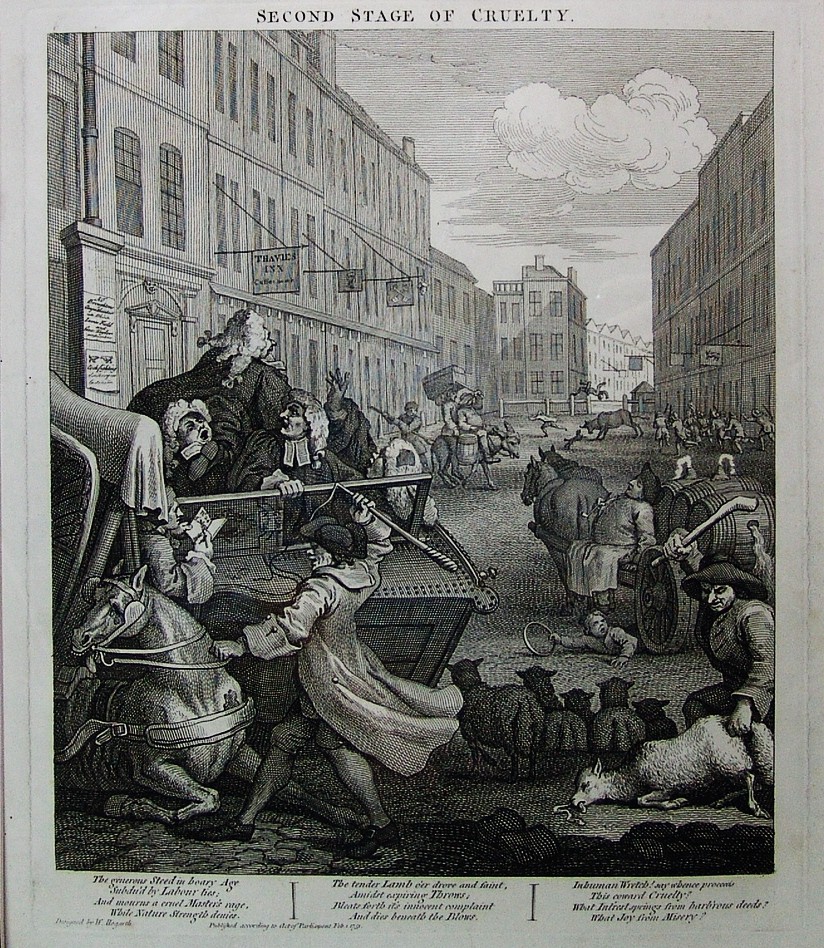

In The Second Stage Of Cruelty (Fig. 2) the violence moves from the childhood arena of “play” to the adult world of work. Nero, now a man, thrashes the horse (which has broken its leg) drawing an overloaded carriage which has overturned. The street is full of abuse; a sheep is bludgeoned, a horse goaded. At least the enraged bull at the rear exacts a little revenge. But on the right of the picture we see a further turn in the narrative as a child innocently bowling a hoop is crushed under the wheels of a cart. The drayman is asleep, perhaps after drinking some of his own foaming cargo.

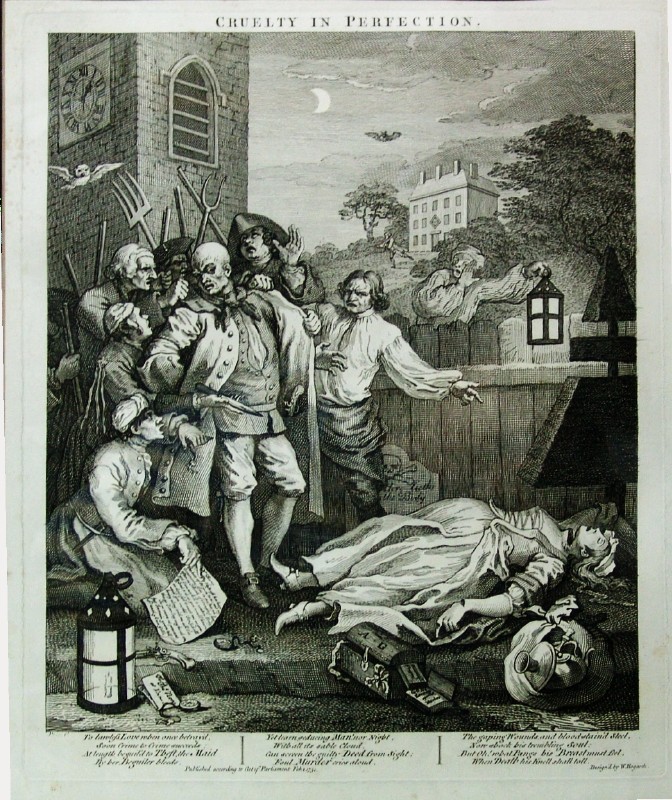

The third print, Cruelty in Perfection (Fig. 3), loses the animals, save for an observant owl and a bat, altogether. Nero is apprehended next to the body of his lover whose throat and wrist have been slashed.[3] She is apparently pregnant, and her note (“To Tommy”) reveals that she has stolen from her mistress, as he had wished, the loot which lies beside her. The much-reproduced final scene (Fig. 4) shows Nero being anatomised before a learned audience following his execution. The old dog, about to eat Nero’s heart, harks back to his younger counterpart from Plate 1. Order is restored, the vice evident in childhood progresses to its inevitable conclusion, the wages of sin is death.

So much is familiar. But more is at stake here than a rather hackneyed eighteenth-century narrative on the aetiology of murder. The old dog takes us back to the young one. Let us too return to the first Plate, for time seems to me to be crucial to understanding the series. By this I mean not simply that the sequence is predicated upon the passage from childhood to death, though so accustomed are we to seeing such narrative movement nowadays (think comic strips) that we overlook the fact that, whilst not unique,[4] and a Hogarth commonplace, it’s still rather a novelty in the work of distinguished eighteenth-century painters. But time plays a more specific and pointed role in these particular pictures.

In The First Stage the boy drawing a gallows on the wall is clearly foreshadowing the future, a technique which the artist has used elsewhere.[5] But let us also pause at a couple of other things which the picture reveals. We have said that Nero is “in the care of” the parish, but clearly supervision doesn’t extend particularly far. And names mean a lot in Hogarth. “Nero” invokes the spectacle of unmatched cruelty, but Nero was also the Emperor, the ruler and personification of the state. We should perhaps be alert to failings of the Establishment in this apparently personal story. There they are in the Second Stage too. Who is it who overloads Nero’s carriage? It is lawyers, their upset occurring outside the Thavie’s Inn coffee house, Thavie’s Inn being one of the oldest Inns of Chancery.[6] There’s a pointer to the future too, in the advertisement on the wall for a boxing match between James Field and George Taylor. Taylor was capitally convicted of burglary on 12 September 1750.[7] Of James Field we will have much more to say. Of the circumstantial, though I confess strong, evidence of Nero’s guilt in Plate 3 I have already drawn attention in the notes.

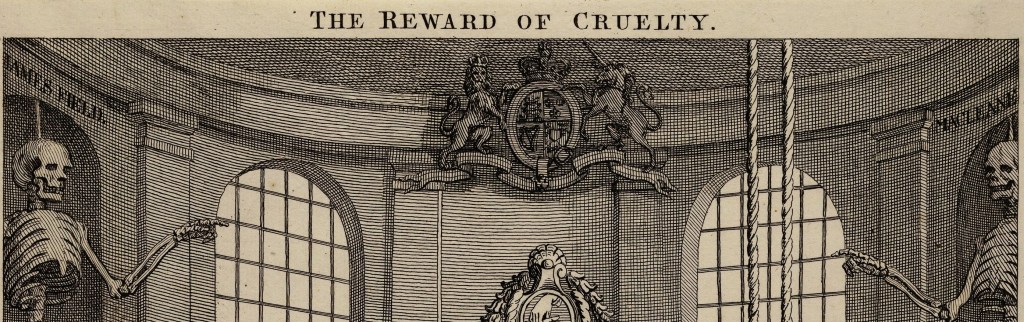

Finally we reach the famous anatomisation scene of Plate 4. I have always been troubled by the dating of this series of prints, for they are inscribed in the plate as “Published according to Act of Parliament Feb. 1. 1751.” The Act in question was the Engraving Copyright Act 1735 which required such information.[8] The celebrated Murder Act of 1752 had not been passed when Hogarth issued the series,[9] and it was this Act which generalised and extended the practice of post-mortem dissection for murderers. Of course the practice had been carried out on a limited basis prior to the Murder Act,[10] but the dating nagged at me. It was not neat. Hogarth may be forceful, but he is usually neat.

The Plate is titled The Reward of Cruelty. Note that ambiguous “Of”: this is not the reward “For” cruelty, but the “Of” invites the question as to whose cruelty is at play here. Clearly the scene depicted is, to an extent, invented for dramatic and artistic effect: I do not believe that dogs were allowed into the dissection theatre to eat the entrails of felons, whilst the cauldron for boiling the flesh off the bones seems much too small (it contains three skulls already!), and too noxious in its positioning, to reflect any contemporary reality. Hogarth wants us to look at the skeletons already prepared and displayed in the alcoves at the rear of the theatre, which point to one another. On the right is the “Gentleman Highwayman” James McLean, executed in October 1750. But in addition to McLean’s lifeless skeleton, another character in the assembled audience wants us to take note of the one on the left, pointing to the bones whilst looking not at them, but at us. The skeleton is that of James Field.

Field, the boxer, was convicted of robbery on 16 January 1751, a point which, even when they have noticed it, seems to have misled some commentators. For Field was not actually executed until 11 February.[11] In other words, Field’s anatomised body is depicted in Hogarth’s engraving whilst the man himself was still alive! What on earth is going on here? Now look again at the central figure, who has been assumed to be “the chief surgeon”.[12] But he isn’t a surgeon. He wears the bands of a judge, and his headgear seems to me like a black cap. I thought at first that Hogarth was depicting him blind. This would have been symbolically consistent with other pictures: Goodchild in Industry and Idleness (Plate 10) turns away and covers his eyes in condemning Idle, thereby ignoring the left-handed oath of the witness and the bribe being taken by the court official. Actual blindness is displayed in the figure of Lord Albermarle Bertie, seated at the centre of proceedings in Hogarth’s The Cockpit of 1759, a print which shows that animal cruelty is not simply the preserve of the lower classes. In the recognition of this depiction of judicial blindness my own eyes were partially opened. But only partially so.

The day before I went to deliver a version of this account at a gathering to commemorate the scholarship of the late Patrick Polden, a very fine legal historian and a good friend, I found myself standing on the stairs looking again into the face of Hogarth’s judge. Then I realised that I had seen the hooded, not closed, eyes and the heavy jowls before.

I am sure that this is John Willes, then Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, who appears as the main figure of Hogarth’s savagely satirical painting, The Bench (c. 1757) (Fig. 5).

If I am right in this, then the identification is an apt and pointed one. It was Willes who had repeatedly refused to pardon Boscaven Penlez, convicted of riot in 1749 and widely believed to have been innocent.[13] The execution caused widespread public outrage and the risk of the body being rescued by the crowd was only narrowly avoided by a promise that the corpse would not be handed to the surgeons. Hogarth must surely have been aware that similar unease was feared over the imminent execution of James Field. The authorities clearly understood, for The Gentleman’s Magazine reported that when Field’s hanging did take place “his legs were chained together to prevent a rescue.”[14]

But Hogarth was looking into the future at a time immediately before Field had died, when talk that anatomisation would become a prescribed routine punishment was in the air. He’s showing, not the conclusion of a simple narrative of retribution, but pointing to that future, when multiple skeletons would be boiled at the instigation of men like Willes. His audience is a double one: those who would read the simple but brutal narrative of the cheap prints and Hogarth’s more powerful and influential friends who might recognise the personal dimension of the caricature.[15] The reward for the cruelty of Nero is his grisly death, the reward for the cruelty of Willes is his centrality in the system, the reward of cruelty more generally lies in the parliamentary gift of the State.

Only the animals retain their innocence in Hogarth’s world of cruelty. I hope that the dog enjoyed his meal.

————-

Author bio: Richard W. Ireland has written extensively on the history of crime and punishment, including its representation in his other passion, visual art. A previous exploration of the connection between criminality and visual representation appeared in November 2023: On Delight in Legal History.

Images:

Figure 1: William Hogarth, The First Stage of Cruelty: Children Torturing Animals, 1751. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2: William Hogarth, The Second Stage of Cruelty: Coachman Beating a Fallen Horse, 1751. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 3: William Hogarth, Cruelty in Perfection (The Four Stages of Cruelty), 1 Feb 1751. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Banner image and Figure 4: William Hogarth, The Reward of Cruelty (The Four Stages of Cruelty), 1 Feb 1751. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5: William Hogarth, The Bench, c. 1757. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

The author has adjusted the tone and contrast of these images.

Notes:

[1] See I.A. Bell “Industry and Idleness: Representing The Criminal” in Proceedings/Anglistentag 1995 Greifswald, ed. J. Klein and D. Vanderbeke (Tübingen, 1996), 29-31. For the “descent into crime” narrative more generally see P. Rawlings, Drunks, Whores and Idle Apprentices: Criminal Biographies of the Eighteenth Century (London, 1992). Both of these authors, the former no longer with us, have contributed enormously to my enjoyment of academic life over many years. The identification of two distinct narratives invites reflection on the different audiences which may have recognised them.

[2] See D. Bindman, Hogarth (London, 1981), 178-180; M. Hallett and C. Riding, Hogarth (London, 2006), 192-194; and the excellent J. Uglow Hogarth: A life and A World (London, 1997), 500-506.

[3] We assume, indeed the verse below specifically mentions, murder and the victim’s finger points in death to a tract entitled God’s Revenge Against Murder. So it may very well be, but I don’t reject entirely the idea that it was committed by someone else, or even the possibility of “self-murder”. The note describes “Ann Gill’s” pangs of conscience, she has instigated the meeting, the cut wrist is an interesting detail. I raise the question not as some bizarre piece of retrospective “victim blaming” but merely to point out that, bloody knife notwithstanding, Nero’s guilt is, like Tom Idle’s in Industry and Idleness, not unequivocally established by Hogarth’s own illustration. We assume it.

[4] I take particular pleasure in the medieval practice of painting “past” and “present” scenes on the same panel. For this, and a grisly early precursor to Hogarth’s engraving, see R.W. Ireland, “‘He hanged Rumbold…’: the iconology of judicial partiality in the middle ages,” Law and Critique 7 (1996), 3.

[5] See Industry and Idleness Plate 5.

[6] The Inns of Chancery were educational establishments for lawyers.

[7] See The Digital Panopticon George Taylor, Life Archive ID obpt17500912-67-defend509 (https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpt17500912-67-defend509). Version 1.2.1, consulted 29th November 2024.

[8] 8 Geo. II c.13. I’m grateful to Lloyd Roderick for his help here.

[9] 25 Geo. II c.37. The date is sometimes erroneously given as 1751 in consequence of confusing calendar with regnal years; 25 Geo. II began on 11 June 1751.

[10] See the classic discussion by P. Linebaugh, “The Tyburn Riot Against The Surgeons” in Albion’s Fatal Tree, ed. D. Hay, P. Linebaugh, J.G. Rule, E.P. Thompson and C. Winslow (Harmondsworth, 1977), 65.

[11] See The Gentleman’s Magazine 21(1751): 38.

[12] Hallett and Riding, Hogarth, 194; Uglow, Hogarth, 503.

[13] “Our account informs us that the king still inclined to pardon [Penlez and his pardoned co-convict Wilson], and that the chief justice [Willes] was three times sent for and consulted on this occasion; but that he still persisted in his former opinion”: The Newgate Calendar (my ed. London, 1933), 426. For the Penlez case see Linebaugh, “Tyburn Riot”, 89-102 and T. Hitchcock and R. Shoemaker, Tales From The Hanging Court (London, 2006), 71-79.

[14] See note 12 above.

[15] Helen Palmer rightly pushed me on the question of how many would recognise Willes: I think this duality addresses that issue.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I wonder if the publication date of Hogarth’s work is an Old Style date, disregarding the provisions of Chesterfield’s Act? So that New Style it would be February 1752?

LikeLike

From RWI: ‘Interesting, thank you. I have been much exercised by this point. I think (hope?) that the internal chronology of the piece is consistent, but the vexed (and vexing!) question of calendar reform might perhaps have been considered in a note. I’d be happy to hear more from you or anyone else who might give a definitive answer.’

LikeLike