Posted by Krista J. Kesselring, 6 January 2025.

Pardons seem suddenly topical yet again. At the last U.S. presidential transition, many people had wondered which of his political allies Donald Trump would free from criminal sanctions on his way out the door and whether he might even pardon himself. We’re now seeing more pardons by another outgoing president. Though ‘lame-duck’ presidential pardons have become something of a tradition, President Biden’s final acts of clemency have been unusual in their number and nature – most controversially, including an unconditional pardon for his son.[1] What will be even more unusual is a mass pardon on Inauguration Day: the incoming president has pledged to grant clemency on Day One of his new administration to many, if not all, of the people who stormed the Capitol on 6 January 2021. Unusual, but not entirely so: talk of an inaugural pardon is somewhat reminiscent of the pardons that English kings and queens used to give at their coronations.

The news of presidential pardons back in January 2021 prompted reflections on this blog on controversies over the pardoning power in England’s history, focused on King Charles II’s use of the royal pardon to halt parliamentary proceedings against one of his ministers. The ‘Glorious Revolution’ that ousted Charles’s successor, King James II, brought new constraints on a king’s ability to pardon in defiance of parliamentary limits; a monarch could no longer use the ‘non obstante’ (notwithstanding) clause to set aside earlier attempts to limit the king’s pardoning power. The 1701 Act of Settlement that followed made it clear that a royal pardon could not thereafter impede an impeachment.[2] The constitutional revolution gave teeth to the notion that a king could pardon offences against himself but had to avoid pardons that impinged upon the public interest as represented in parliament. Before long, the once traditional practice of giving a general pardon at the beginning of a new monarch’s reign would disappear, too. Kings in some parts of the world still bestow coronation pardons—in Thailand in 2019, for example—but in England the practice ended in the early eighteenth century.

English coronation pardons grew from medieval roots. Like other royal acts of grace, they drew on both classical and Christian conventions of clemency to show the sovereign’s power to give as well as take life. They had pragmatic benefits, too, in cleaning slates and tidying away difficult legal issues, sometimes making political necessity look like generosity or lordly magnanimity. They did not free an individual from a private prosecution by a victim, but could release recipients from any action by the king, for everything from unpaid fines through to major crimes. Medieval kings started to use pardons to mark special occasions—individual and group pardons at Easter, for example, but also broadly applicable general pardons covering a wide range of offences to mark events important in their own lives or reigns, such as royal marriages and births. Edward III gave the first general pardon through parliament to mark the 50th anniversary of his accession, a Jubilee with biblical connotations of atonement and mercy. General pardons could also complement what we might term ‘transitional justice’ in the aftermath of rebellions or at the outset of new reigns.

Henry V proclaimed a general pardon upon his coronation in 1413, to try to still the ‘whirlwinds of discord’ that accompanied his father’s seizure of the throne.[3] In time, other kings would do much the same. Henry VII certainly deemed a pardon prudent shortly after his own usurpation in 1485. He gave general pardons throughout his reign, through parliament or on his own, including one from his deathbed as a token of remorse before he met his Maker. His son, in turn, proclaimed a general pardon days after his accession. A chronicler said Henry VIII’s inaugural pardon helped lighten the heavy hearted of ‘all their old grudges and rumours, and confirmed their new joy by the new grant of his pardon’.[4] The councillors who governed on behalf of Henry VIII’s underage heir, Edward VI, harkened back to Henry’s accession pardon but decided to await the more propitious timing of the boy-king’s coronation day on 20 February 1547 for his inaugural pardon, to add to the festivities to mark the fresh start of a new reign.[5] Kings already swore solemn oaths at their coronations to rule with mercy; granting a general pardon during the event made that mercy manifest.

Thereafter, a new sovereign’s officials and heralds proclaimed the coronation pardon near the end of the public ceremony, while the bishops, dukes, and earls paid their personal homage to the king or queen and before the final anthem of praise. The terms of the pardons differed in excluding specified offences or offenders. But everyone who was anyone—and then some—paid the fees to get their names added to the pardon rolls that followed, whether implicated in wrong-doing or not. Roughly 800 people availed themselves of Edward VI’s coronation pardon, for example. Thousands more would make use of the pardons issued by each of the later Tudor and early Stuart monarchs in their coronation ceremonies.[6]

But despite all the praise of mercy as a necessary attribute of good lordship, not everyone thought all pardons appropriate. One Elizabethan member of parliament, distraught that his queen refused to execute opponents who endangered not just her but her realm, too, summed up some of the concerns:

Oh! But mercy, you will say, is a commendable thing and well beseeming the seat of a Prince. Very true, indeed: but how long? Till it bring justice in contempt, and the state of the Church and Commonwealth in danger?…And what got her Majesty, I pray you, by this her lenity? Even as much as commonly one shall get by saving a thief from the gallows: a heap of treasons and conspiracies’.[7]

Critics then and later derided some uses of mercy as weak, ‘womanish’, or even cruel. Preachers warned against ‘cruel mercy’—whether from juries acquitting the guilty or princes pardoning the undeserving—as harming the state and its laws. In a 1619 sermon, William Pemberton allowed the truth of Psalm 85:10, that mercy and justice must embrace, but warned that ‘equity walks in the golden mean between rigorous severity which punisheth any too much, and cruel mercy which spareth a few to the hurt of many’. Kings, like God, must show mercy to some through their judgements on others.[8] Only a tyrant showed no mercy, but self-interested, selfish, or ‘cruel mercy’ marked a tyrant, too.

The men who served in parliaments sometimes tried to constrain uses of the royal pardon. Medieval parliaments criticized the pardoning of vicious, unredeemable men to secure bodies for the king’s army or money for his treasury, for example. But England’s rulers continued to issue pardons ‘notwithstanding’ any statutes to the contrary for a long time to come.[9] As with other aspects of the royal prerogative, the pardoning power became especially contentious under the early Stuart monarchs, as Cynthia Herrup has shown. Members of parliament protested pardons to the ‘papists’—Catholics—they feared as perfidious dangers to the ream. Many general pardons appeared as statutes, acts of royal grace passed through parliament, ostensibly as tokens of the monarch’s gratitude for a parliamentary vote of taxes; in the early 1600s, members of parliament started trying to negotiate their terms, criticizing them as either too generous or too narrow and blocking the passage of some.[10] But coronation pardons came as royal proclamations, at the ‘mere motion’ and unchecked gift of the sovereign. In due course, they would disappear.

The growing belief that crimes offended not just the sovereign but also the public seems to have hindered general acts of grace unfiltered through parliaments. After the civil wars and republican years of the mid-1600s, Charles II had good reason to engage in abundant if carefully delimited acts of amnesty to try to draw a line under the conflicts of the previous decades. His coronation pardon was supplemented by a parliamentary Act of Free and General Pardon, Indemnity, and Oblivion that, in Stephen Roberts’s words, ‘cleverly demonstrated his respect for the institution which had fought against, tried and executed his father’.[11]

Charles II’s brother and successor, though, ran into new problems. Openly Catholic in a profoundly Protestant nation, James II had faced significant opposition to his succession, including several plots and conspiracies. He did not issue a pardon at his coronation on 23 April 1685, a decision that seems not to have been entirely his own or at least not to his liking. A Quaker who petitioned the new king on behalf of his imprisoned co-religionists reported that James told him he had to defer his inaugural pardon until his first meeting of parliament because ‘some persons who are obnoxious, by being in the late plot, would thereby have been pardoned and so might have come to parliament, which would not have been safe’.[12] But nothing came from that first parliament, either. Fresh acts of rebellion intervened that neither the king nor many of the nation’s leaders wanted indiscriminately pardoned: a Protestant, bastard son of the late king, James Scott, duke of Monmouth, secured a following in the West Country—and a coordinated rising in Scotland—to try to overthrow James. Defeated at the Battle of Sedgemoor on 6 July 1685, Monmouth himself was quickly dispatched but his supporters remained a threat.[13]

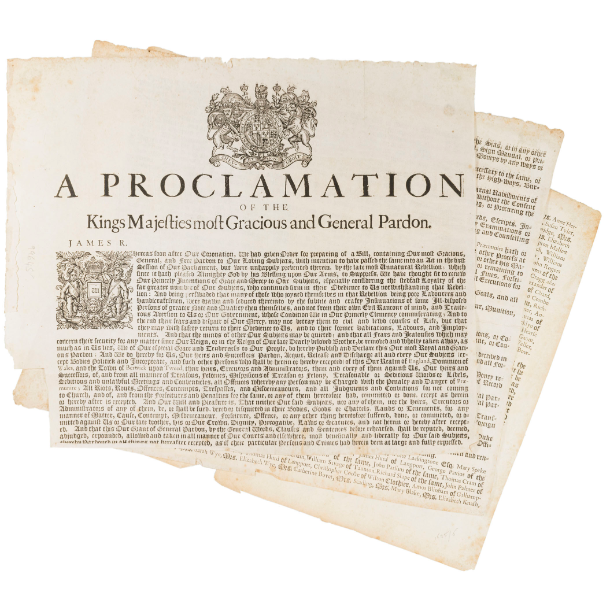

James only proclaimed his first general pardon on 10 March 1686, a pardon that did double duty in tidying away the sanctions for participants in Monmouth’s Rebellion. Hundreds of the rebels had already been executed or transported to the West Indies, but others remained. Thinking fit to ‘renew Our Princely Intentions of Grace and Mercy to Our Subjects’, to reward the loyal and forgive the repentant, James proclaimed a broad general pardon akin to coronation pardons past. In respect to the recent rebellion, this act of grace excepted the rebellion’s leaders and a long list of named individuals but was open to any of the rank and file who came in to claim it within three months, if they showed their amendment and returned to their former labours.[14]

Of course, this act of grace did not suffice to secure James the obedience he needed. His son-in-law, William of Orange, landed with a sizable invasion force on 5 November 1688 and quickly rallied many of the king’ s subjects to his side. James issued a pardon the following week to any rebels who would go back to their homes, to try to reverse the early effusion of support for William, but to no avail. By December James was gone. Coronation pardons would soon quietly disappear. Especially after parliament handed the crown to the Hanoverian line in 1714, it came to be generally accepted that the royal prerogative of mercy would only be used upon ministerial ‘advice’ (a euphemism for ‘instruction’).[15] Coronations would continue to have plenty of pomp, but no pardons.[16]

In the post-Revolutionary years, the royal prerogative of pardon had come to seem like a power that should and could be constrained to better serve a public good. When George III’s rebellious former subjects in the new United States of America met to devise their own constitution, they grappled with whether or how to enshrine the power to pardon in their founding charters. The compromises they reached ensured that some of the problems that had previously plagued pardoning in a monarchy would be revived in the new republic.[17] In a recent overview of controversial pardons in U.S. history, Joshua Zeitz ends by asking:

‘In a constitutional democracy, should one person enjoy the right to overturn the wisdom of judges and juries? And if so, what limits should be placed on that power?’

Images:

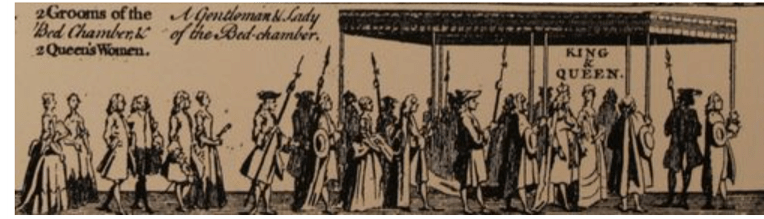

Images of the coronation of James II come from Francis Sandford, The History of the Coronation of the Most High, Most Mighty, and Most Excellent Monarch, James II (London, 1687), public domain.

Medieval coronation, from Froissart’s Chronicles, via Wikimedia Commons.

Coronation of Edward VI, from the engraving by James Basire via Wikimedia Commons.

Coronation of James I, from an anonymous 1603 engraving via Wikimedia Commons.

George II’s coronation procession, from an anonymous engraving reproduced in Parliament Past and Present by A. Wright and P. Smith (London, 1902). Public domain, via Sandra Tuppen’s post on the coronation on the British Library blog.

Notes:

[1] See the White House briefing note for an overview of President Biden’s categorical commutations or pardons of groups of people and a description of his 12 December 2024 announcement as ‘the largest single-day grant of clemency in modern history’. For the controversy over his pardon for his son, Hunter Biden, see, e.g., this BBC News story.

[2] On pardons after the Revolution of 1688/9, see J.M. Beattie, ‘The Cabinet and the Management of Death at Tyburn after the Revolution of 1688-1689’, in The Revolution of 1688-1689: Changing Perspectives, ed. L.G. Schwoerer (Cambridge University Press, 1992), 218-33; works by Simon Devereux, e.g., ‘Execution and Pardon at the Old Bailey, 1730-1837’, American Journal of Legal History, 57.4 (2017), 447-94; and the classic essay by Douglas Hay, ‘Property, Authority and the Criminal Law’, in Albion’s Fatal Tree: Crime and Society in Eighteenth-Century England, ed. D. Hay et al (Pantheon, 1976), 17-64.

[3] Quotation from the Calendar of the Close Rolls, Henry V (1413-1419), 67-8. On medieval pardons, see Susanne Jenks, ‘Exceptions in General Pardons, 1399-1450’, in The Fifteenth Century, XIII: Exploring the Evidence, ed. Linda Clark (Boydell and Brewer, 2014), 153-82 as well as the list of general pardons Jenks posted online; Helen Lacey, The Royal Pardon: Access to Mercy in Fourteenth-Century England (Boydell and Brewer, 2009), especially for the significance of the Jubilee; and the introductions to Hannes Kleineke’s calendars of the medieval pardon rolls, e.g., Pardon Rolls of Edward IV and Henry VI, 1468-1471 (List and Index Society, 2019). On the role of parliament as sometimes something more than just a stage for medieval kings’ gifts of grace, see Kleineke’s post on The National Archives’ blog, ‘Good Will to All: Henry VI’s Christmas Pardon of 1470-71.’

[4] Hall’s Chronicle, ed. Henry Ellis (New York, 1965), 423 (Henry VII’s first pardon), 504 (deathbed pardon), 506 (Henry VIII’s ratification of his father’s final pardon and then his own); quote at 507. Tudor Royal Proclamations, ed. Paul Hughes and James Larkin (Yale University Press, 1964), i. no. 59 (confirmation of Henry VII’s pardon, 23 April 1509) and no. 60 (Henry VIII’s accession pardon, 25 April 1509). On pardons in the sixteenth century, see K.J. Kesselring, Mercy and Authority in the Tudor State (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

[5] Kesselring, Mercy, p. 64-5, citing The National Archives (Kew), SP 10/1, no. 2.

[6] The names of people who obtained copies of the coronation pardons can be found in the supplementary patent rolls in The National Archives (Kew), C 67: e.g., C 67/64 (Edward VI); C 67/65-66 (Mary)[ C 67/67-68 (Elizabeth); and C 67/69-71 (James). No such rolls seem to exist for Charles I’s coronation pardon, unfortunately.

[7] J.N. Neale, Elizabeth I and Her Parliaments, 1584-1601 (New York, WW Norton, 1966), 111, quoting a speech from Job Throckmorton. For this and other criticisms of royal mercy in Elizabeth’s reign, see Mary Villeponteaux, ‘Dangerous Judgments: Elizabethan Mercy in The Faerie Queene’, Spenser Studies 25 (2010), 163-85.

[8] William Pemberton, The Charge of God and the King to Judges and Magistrates for Execution of Justice (London, 1619), 90. For other discussions of ‘cruel mercy’, see also, e.g., William Hayes, The Paragon of Persia, or, the Lawyer’s Looking Glass (Oxford, 1624), 12-13 and Humphrey Sydenham, Sermons upon Solemne Occasions (London, 1637), 78, 172.

[9] See Jenks, ‘Exceptions’ and Lacey, Royal Pardon.

[10] Herrup, ‘Negotiating Grace,’ 124-140.

[11] Stephen Roberts, ‘The Importance of Royal Pardons in Restoration England’, History of Parliament blog. For the Act, see 12 Car. II, c. 11.

[12] Memoirs of George Whitehead, ed. Samuel Tuke (York, 1830, 2 vols.), ii. 179. On the delay, see also Francis Sandford, The History of the Coronation of the Most High, Most Mighty, and Most Excellent Monarch, James II (London, 1687), 99.

[13] On Monmouth’s rebellion, see, e.g., Robin Clifton, The Last Popular Rebellion: The Western Rising of 1685 (St. Martin’s Press, 1984) and W. MacDonald Wigfield, The Monmouth Rebels (Somerset Record Society, 1985), which prints James’s pardon in Appendix 1.

[14] A Proclamation of the Kings Majesties Most Gracious and General Pardon (London, 1686).

[15] For William and Mary, see J. Wickham Legg, Three Coronation Orders (London, 1900), 30, 31, 155. For Anne, see William J. Thoms, The Book of the Court (London, 1844), Section VIII, Coronation Ceremonies, 440. In 1822, George IV tried personally intervening in pardoning decisions but was firmly rebuffed by his Home Secretary; see Brenda Gean Mortimer, ‘Rethinking Penal Reform and the Royal Prerogative of Mercy during Robert Peel’s Stewardship of the Home Office, 1822-7, 1828-30’, PhD Dissertation, University of Leicester, 2017, 93ff. See too the overview in the Commons Library Research Briefing: The Royal Prerogative and Ministerial Advice [pdf], 8 July 2024, 64-7.

[16] Legg notes that the words pertaining to the pardon were omitted from George II’s coronation order and all those following: Three Coronation Orders, 154, 155. An account of the coronation of George I in 1714 suggests that it was still intended to appear then: see An Exact Account of the Form and Ceremony of His Majesty’s Coronation (London, 1714), 17.

[17] See, e.g., William F. Duker, ‘The President’s Power to Pardon: A Constitutional History’, William and Mary Law Review, 18 (1977), 487-503. Adam Zamoyski nods to these conflicts and notes as an irony that the power to pardon is now more constrained in many monarchies (including the British) than in democracies: ‘The Pardon Paradox’, 13 December 2024, Engelsberg Ideas.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.