Guest post by Andrea McKenzie, 12 March 2024.

The lawyer and MP George Treby (1644-1700) was one of the leading opponents of Charles II (r. 1660-85) in both Parliament and the courts. Treby was Chairman of the Commons’ “Secret Committee” investigating the Popish Plot (think Mueller Investigation, Restoration-style), counsel in several high-profile political trials of the early 1680s, and Recorder, or chief sentencing officer, of London from 1680 until 1683, when the City’s charter was revoked in the so-called “Tory Revenge.” After the ultimate triumph of the “Whigs” in the Revolution of 1688/9, Treby was reinstated as Recorder and rewarded for his past services, becoming solicitor-general and then attorney general in 1689, and Lord Chief Justice of the Common Pleas in 1692.[1]

In the late 1660s, however, when he began to keep the notebooks that are the subject of this post, Treby was just one of many law students at the Middle Temple, one of the Inns of Court in London.[2] Legal education in this period was in flux: during the Civil War and Commonwealth of the 1640s and 50s, the older system of “readings” delivered by benchers, or senior barristers, supplemented by moot courts and disputations, broke down and even after the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 was never fully re-established, eventually falling casualty to what David Lemmings has identified as a larger seventeenth-century “decay in the communal life in the inns.” Law students thus were obliged to fall back on their own resources, and that of their families. They studied legal reports and a growing number of available printed law books; many had attended university (Treby studied at Exeter College, Oxford, although never completed his degree); some paid hefty fees to apprentice to solicitors to learn the practical aspects of the law; most were encouraged to attend the courts at Westminster Hall or the Old Bailey and take notes of the cases or trials they heard there.[3]

George Treby’s two volumes of notes or “Reports” in the Middle Temple Library cover the period from 1667 to 1672 and focus mostly on cases from the King’s Bench but also include some from Common Pleas and Chancery and a few from the Old Bailey and Exchequer. Most appear to have been based on detailed first-hand observation, likely facilitated by Treby’s acquisition of a skill contemporaries called, variously, shorthand, stenography, brachygraphy, “swift” or “secret writing.”[4] As Treby himself puts it in his notebook, “In the vacation between Mich[aelmas] & Hill[ary] terms [December 1667-January 1668] I learnt to write short hand of Mr [Henry] Hatsell” – his old Oxford schoolmate, fellow Middle Templar and future brother-in-law.[5] (Here and throughout, shorthand is bolded).

As recent scholars of shorthand have reminded us, early modern stenography was not simply synonymous with cryptography, or secret code or content: it was valued both for the speed with which an experienced practitioner could record speech and also for its “spatial efficiency.”[6] As I have discussed elsewhere, many of Treby’s later shorthand notations in his papers held in the Derbyshire Record Office were pedestrian enough, consisting of queries, summaries or various lawyerly glosses (“breviated”, “transcribed”, “I have the original”, “this is but hearsay”, etc.). But others referred, however obliquely, to rumours and suspicions about court skulduggery, secret Anglo-French diplomacy and the crypto-Catholicism of the king.[7] Shorthand was an effective, if not infallible, means of keeping sensitive material from prying eyes, employed by contemporaries such as the nonconformist minister Roger Morrice and the naval official and diarist Samuel Pepys—the latter resorting to additional safeguards to protect particularly compromising material, such as a “polyglot” of modern and classical languages.[8]

Early modern shorthand is especially difficult for researchers to crack because there were many different systems (estimates range as high as over forty in the late seventeenth century), all using similar or identical symbols to denote different letters, words or sounds.[9] For instance, no fewer than eight distinct shorthand systems of this period used a character approximating the Latin consonant “c” to correspond to eight different letters of the alphabet.[10] Treby’s shorthand was challenging for me to decode because he left neither a key nor any clue as to the system he was using (which I was ultimately able to determine was that of Jeremiah Rich). Not only were there variations between different iterations and editions of the same system of shorthand, but also multiple options within each system; the writer could choose to write either alphabetically or by arbitrary symbols, or a combination of both. Moreover, Treby, like other contemporaries, adapted and personalised his shorthand, simplifying or ignoring some rules and inventing new characters.[11]

George Treby was above all, a clear and methodical thinker (with thankfully neat handwriting!), explicitly explaining to his imagined reader or future self the reasons for his editorial choices. At the beginning of the first volume, Treby explained that “All that is written within the Paratheses [sic] (as the Printers call these marks []) is my own Insertion & Addition, & not the words of the Court of person speaking in the case where they are placed.”[12] Treby’s shorthand insertions seem to have been similarly intended to flag additional information and interventions that were not part of the official record.[13] Often the insertions were innocuous corrections, updates, queries, explanations or summaries. Some shorthand notes contained pointed, if often cryptic, attacks on the king or his favourites (I will explore these further in forthcoming work). Others, such as those I will discuss here, were gossipy, critical, and irreverent – or simply personal or private; that is to say, “off the record.”

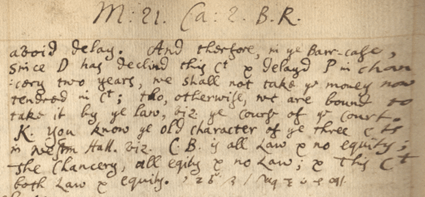

In a section on the “rules & course of the Court” from late 1669 the Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench Sir John Kelynge repeats what was clearly an old saw: “You know the old character of the three courts in Westminster Hall viz. [namely] C.B. [Common Pleas] is all Law & no equity; the Chancery, all eqity & no Law; & this Court [King’s Bench] both Law & equity.” To this Treby adds, in shorthand, what must have been the conventional comic follow-up and may have been murmured that day in the court, to laughter: “and it is usually added the Exchequer neither law nor equity.”[14]

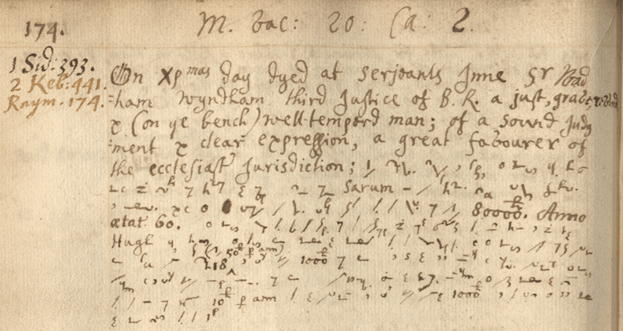

Treby sometimes included short obituaries of prominent courtroom figures. In late 1668 he recorded the death of the judge Sir Wadham Wyndam, writing in longhand:

M[ichaelmas] Vac[ation] 20 Ca 2 [1668]

On Christmas day dyed at Serjeants Inn Sir Wadham Wyndham third Justice of B.R. [King’s Bench] a just, grave, reverend & (on the bench) well-temperd man; of a sound judgment & clear expression, a great favourer of the ecclesiast jurisdiction;

What follows, primarily in shorthand, is markedly less deferential:

but excessively covetous and sordid he would go recoup with his clerks for half their fees [;] come from Sarum [Salisbury] in a hackney coach lived sparingly and meanly &c he left a very large estate to the value of about 80,000£. Anno aetat [aged] 60. He would use to tell the story of the artifice his father practiced to make him and his brother Hugh good husbands He told them when they went to the university that he would at first allow them such an exhibition [allowance] <set (about 50£ per annum)> and lay out 1000£ for them and as they did manage that yearly allowance he would augment that and lay out more money for them accordingly upon their thrifty management he added when they came to the inns of court 10£ per annum to their allowance and laid out another 1000£ and the like he did when they were called to the bar[15]

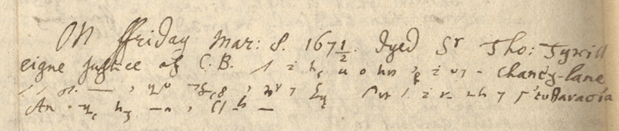

Treby thus communicates not only his contempt for a man who died with an estate amounting to almost £12 million, converted to 2025 values,[16] and yet was too cheap to keep his own coach, but also some interesting information about the costs of seventeenth-century legal education. Treby’s necrologies could also disguise furtive admiration, as was the case with Sir Thomas Tyrill, a justice of Common Pleas who apparently committed suicide.

On Friday Mar: 8 1671/2 dyed Sir Tho: Tyrrill eigne [senior] Justice of C.B. [Common Pleas] at his house which he held during his life in Chancery-lane after a pretty long and gentle indisposition and decay of strength according to his own wish of an ευθανασία [euthanasia] An ingenious honest meek and sweet natured man[17]

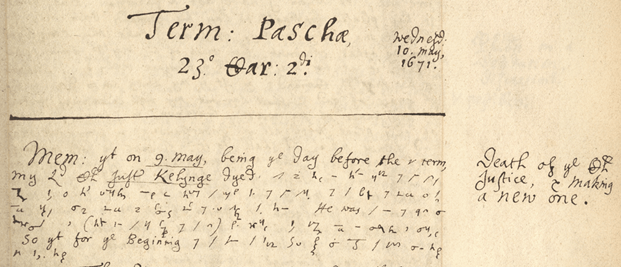

Treby’s obituary of Sir John Kelynge on 10 May 1671 gives us an interesting perspective on the famously irascible royalist judge. After noting in longhand that the chief justice had died on 9 May 1671, the entry continues in shorthand, innocuously enough at first:

at his house in Hatton Garden of an acute fever but he had languished more than half the year before of an ague for relieving of which he took much Jesuit powder [quinine] which tis supposed was of ill consequence to him.He was a man of quick p[arts] uncorrupt and (having been a great sufferer for the king) very courageous but offending much in peevishness and prejudice so that for the Beginning of the term the burden still rested upon T the old prying whoreso[n?] or bawdy whoreso[n?][18]

The evidence of the notebooks makes it clear that the initial “T” does not refer to Treby himself—sadly, as this would be much more interesting!—but rather the puisne judge Thomas Twisden, who would have taken a more active role on the King’s Bench as the chief justice’s health declined. These notes are somewhat ambiguous, but seem to suggest that Kelynge, known for his violent temper and vulgarity (once brushing off the objections of a juryman by quoting Oliver Cromwell’s “Magna Charta, Magna Farta”), had called his fellow justice an “old prying whoreson” and “bawdy whoreson.”[19]

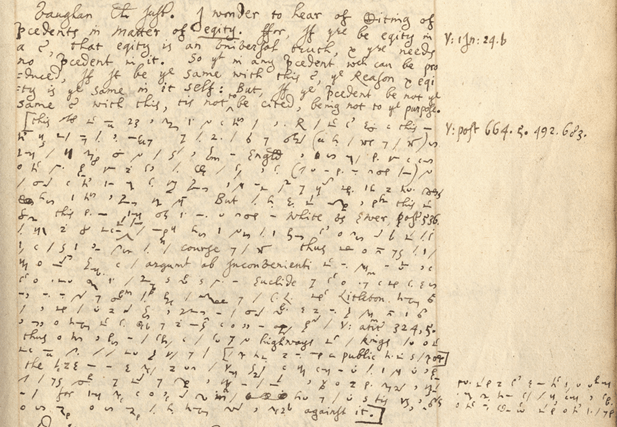

The brilliant young law student was quick to judge the members of the bench by his own high standards, writing in shorthand in the margin next to one of the aging Twisden’s arguments: “I doubt T mistook and his memory does begin to fail him.”[20] In another marginal shorthand comment he reported that “Serjeant Newdigate ridiculously cited one Potts’s case wherein he said the court granted the new trial without any cause at all.”[21] Treby was especially critical of Sir John Vaughan, chief justice of the Common Pleas, today revered for his landmark ruling in Bushell’s Case (1670), effectively upholding the right of juries to return verdicts against the instructions of trial judges. Treby regularly questioned Vaughan’s use of precedents, and even his knowledge of Latin and law French.[22] He was particularly scathing of the justice’s opinion, delivered in a 1670 case involving the forfeiture of lands, that precedent was irrelevant: “I wonder to hear of Citing of precedents in matter of eqity. For, if there be eqity in a [case] that eqity is an universal truth, & there needs no precedent in it…”

In the long shorthand passage inserted in “paratheses” (brackets), Treby writes:

[this assertion was much derided and condemned by all that heard it and I remember it was said thereupon that this man had just wit enough to do mischief for to deny the use of precedent (which shows the course of the court) would bring a great confusion upon all the estates and settlements in England and

hewould invite everyone that thinks he has any reason on his side to commence a suit and so (at least in every new keeper’s time) all the points that had been never so often determined and are now taken for granted whereby business is highly expedited should be heard and determined over again….the truth is this man in this conceit is like the young student that judges things in law to be against law and reason at the first appearance for want of experience and observation in the matter, and yet he is very confident and obstinate in it for being conscious that he does not excel in the skill of the law as tis understood and practiced he would endeavour…to show himself clever and considerable against it].

Treby adds, for good measure, in the marginal shorthand notation: “certainly whatever is said this man has but little learning I never knew him cite a good thing…”[23]

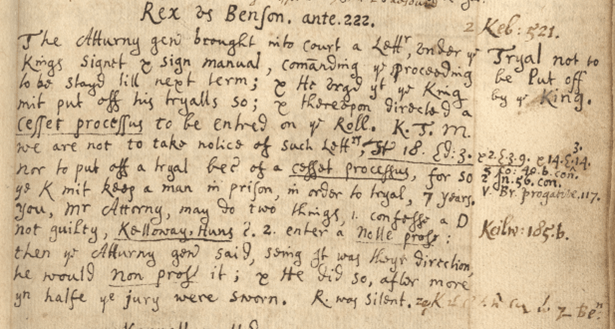

In Rex v Benson (1669) for extortion, three of the four judges (Kelynge, Twisden and Morton) denied the prosecution’s request to delay the trial until the next term to gather more evidence, directing a nolle prosequi (i.e., a dismissal of the charges). While the judges framed their decision as a defence of the rights of the subject—”the King mi[gh]t keep a man in prison, or order to trial, 7 years”—Treby was more cynical, inserting a shorthand line which implied that the reputedly incorruptible chief justice had been swayed by a gratification from the defendant: “Zealous K.[elynge] was said to have silver plate from Be:[so]n.”[24]

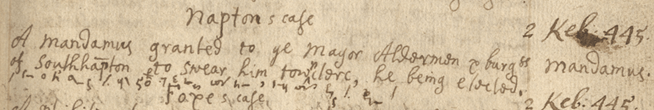

The shorthand occasionally provides behind-the-scenes information fleshing out otherwise prosaic summaries. For instance, in Napton’s case, 26 January 1669, the longhand reports only that a mandamus had been served to the mayor and aldermen of Southampton, obliging them to swear in the plaintiff as town clerk, “he being elected”; the shorthand line inserted below explains their recalcitrance:

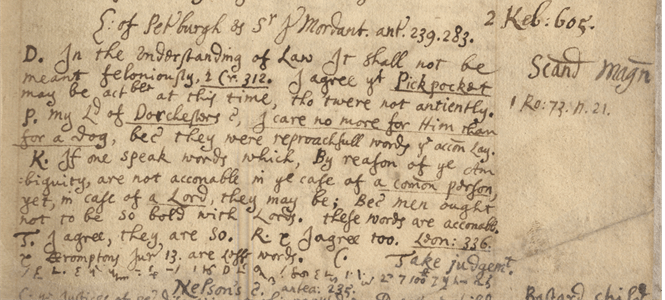

“It seems he had promised to give 50£ if they would elect him and being elected refused to perform it.”[25] In the account of a prosecution by Henry Mordant, earl of Peterborough against Sir John Mordaunt for scandalum magnatum (the defamation of a judge or high official or, as in this case, a peer), Kelynge ruled that the defendant’s calling the plaintiff a “Pickpocket” was actionable “because men ought not to be so bold with Lords.” Treby speculates in shorthand that “the reason why they gave judgement no sooner might be because D[efendant] was provoked to speak these words by violent demand of 100£ for getting him knighted.”[26] The avaricious Peterborough was well-connected, being a close friend of James duke of York, the king’s brother: Kelynge and the other judges may well have feared crossing him.

Treby’s notebooks occasionally hint that powerful interests were at work behind the scenes. In Fortescue v Sr Robert Holt (1672), glossed in the margin as “The Nature & Use of Pleading,” Kelynge’s successor as Lord Chief Justice of the King’s Bench Sir Matthew Hale lambasted the counsel for the defendant for moving “some trifling & captious exceptions to maintain a demurrer” (an objection to the pleading filed by the opposing party). Hale—whom Treby clearly admired—declaimed at length against what he saw as a recent tendency to use “frivolous demurrers…to catch & intricate men.” While maintaining that he himself, while a “Practicer,” had always given opposing counsel the opportunity to amend their pleading rather than deliberately delay a cause, Hale acknowledged there had been some bad apples even in his day: “Tis tru Serjeant [Edward] Henden [1567-1644] did use to practice somewhat otherwise; & went under great disparagement therefore to his grave. (Tho he was before his death made a Baron of Scacc: [i.e., judge of the Court of Exchequer]).” To this Treby added in shorthand: “[I have heard old Mundy say he [Henden] would ne’er let a cause go till he had got o7 or o8£ or more out of it then would move to amend plead any demur[rer] &c] and he would take twenty commissions &c].”[27]

Treby’s shorthand goes on to suggest that Hale was gesturing to more recent abuses, possibly from much higher up:

“Certainly this prodigious good and great man [Hale] took occasion now to censure this great error, the rather because of some countenance which T[wisden]seemed to give to such things several times particularly two days before though he would not then speak it out it maybe because it might seem to reflect…”

This is followed by a long blank space, presumably alluding to an important person, possibly the king himself; the shorthand continues, making a reference to a “passage” two days before involving the chamberlain of London, Sir Thomas Player, a loyalist and former intimate of Charles II who would soon afterwards become a vocal critic of the court.

As Kate Loveman has demonstrated, Samuel Pepys carefully curated his papers to ensure that his shorthand would be preserved and eventually deciphered only by likeminded (and, hence, sympathetic) readers.[28] Like Pepys, Treby clearly hoped that his shorthand would be largely impenetrable to contemporaries (but, unlike him, did not leave behind a library containing the relevant shorthand manuals). Treby’s shorthand, unlike that of Pepys, was uniformly in English, although sometimes mixed with Latin or smatterings of Greek in longhand. But Treby, like Pepys, also used various strategies to obfuscate his more sensitive shorthand notations – in his case, inserting blanks and making cryptic references to marks (such as folded down pages) that seem to have subsequently been effaced or to separate sheets that have since disappeared.[29] Some trails of breadcrumbs may lead down blind alleys, and there are some seventeenth-century firewalls we may never breach; however, with painstaking research into particular contexts and people involved, we can at least make some educated guesses. In any case, George Treby’s Middle Temple shorthand notes confirm what we knew all along: there is a lot going on under the surface of early modern legal manuscripts, if we can somehow read between the lines.

—–

Author bio: Andrea McKenzie is a professor of early modern British history at the University of Victoria (Canada) who specializes in the history of crime and the courts. Her most recent book is Conspiracy Culture in Stuart England: The Mysterious Death of Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey (Boydell & Brewer, 2022).

Images: All images are posted by permission of the Benchers of the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple. I am grateful to the Middle Temple librarian Dr Renae Satterley for bringing these notebooks to my attention and for her kind assistance throughout.

Banner image: George Treby Notebooks, Middle Temple MS2 C, Cases in the King’s Bench, 1667-1672 (2 vols, continuously paginated), 1:175.

Notes:

[1] Paul D. Halliday, “Treby, Sir George (bap. 1644, d. 1700), judge and politician.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 23 Sep. 2004; Accessed 11 Mar. 2025.

[2] George Treby Notebooks, Middle Temple MS2 C, Cases in the King’s Bench, 1667-1672 (2 vols, continuously paginated).

[3] David Lemmings, Gentlemen and Barristers: The Inns of Court and the English Bar 1680-1730 (Oxford, 1990), 90; 95-97; 106.

[4] Frances Henderson, “‘Swifte and Secrete Writing’ in Seventeenth-Century England, and Samuel Shelton’s Brachygraphy,” British Library Journal 2008, article no. 5, 4, doi.org/10.23636/960

[5] 1:94. Henry Hatsell (1641-1714), like Treby, was from Devonshire, the son of Henry Hatsell, the roundhead MP for Plympton in 1658, the same seat that Treby would hold almost continuously from 1677 to 1693 (with the exception of James II’s 1685 parliament).

[6] Hannah Boeddeker and Kelly Minot McCay, ed., New Approaches to Shorthand: Studies of a Writing Technology (Berlin and Boston, 2024), 17, 19.

[7] See my “Inside the Commons Committee of Secrecy: George Treby’s Shorthand and the Popish Plot”, Parliamentary History, 40.2 (June 2021), 277-310.

[8] Mark Goldie, ed., The Entring Book of Roger Morrice 1677–1691, 7 vols.(Woodbridge, 2007–9), 1:130, 1:135; William Matthews, “Samuel Pepys, Tachygraphist,” Modern Language Review 29, no. 4 (October 1934): 397–98; Modern Language Review 29, no. 4 (October 1934): 397–98; Kate Loveman, “Women and the History of Samuel Pepys’s Diary”, The Historical Journal 65 (2022), 1222-1224. Indeed, standard alpha-numerical ciphers were arguably easier to decode than shorthand, even in the absence of a key; see Alan Marshall, Intelligence and Espionage in the Reign of Charles II, 1660–1685 (Cambridge, 1994), 90–91.

[9] Matthews, “Samuel Pepys, Tachygraphist,” 397; Henderson, “‘Swifte and Secrete Writing’”, 4.

[10] Boeddeker and McCay, 34-5.

[11] For more on how I deciphered Treby’s shorthand, and on early modern stenography generally, see my “Secret Writing and the Popish Plot: Deciphering the Shorthand of Sir George Treby,” Huntington Library Quarterly, 4 (Winter 2021), 783-824. Treby, like most of his contemporaries, also used numerous short forms and medieval scribal abbreviations, such as a “p” with a stroke (ꝑ), meaning either “par” or per”: a stroke above a “p,” which stands for pre or prae (e.g. presume); and a curved stroke to the left of a “p,” which stands for pro; (e.g., proved). Various other abbreviations are used throughout, as well as the ubiquitous thorn symbol (Þ), rendered as a “y” by the seventeenth century (yt, ye = that, the) and the tilde (~ ), which conventionally signifies one or more missing letters.

[12] 1:iii.

[13] The notebooks appear to have been fair copies of earlier draft notes that were likely (after he mastered the skill) primarily in shorthand.

[14] 1:302.

[16]According to the National Archives currency converter https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/#currency-result, £80,000 in 1670 equates to just over 9.1 million pounds sterling in 2017; this converted to 2025 values (using https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator) would amount to over 11.9 million GBP. Using the same calculations, an allowance of £50 a year in 1630 would add up to about £8000 in 2025 currency.

[17] 2:718.

[19] ‘Debates of 1667: 3 December’, in Grey’s Debates of the House of Commons: Volume 1, ed. Anchitell Grey (London, 1769), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/greys-debates/vol1/pp54-70 [accessed 9 March 2025]; Nicholas Vincent, Magna Carta: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford, 2012), 95.

[20] 2:663.

[21] 1:202.

[22] 2:523, 2:525.

[24] 1:227; 1:222.

[25] 1:175.

[26] 1:363.

[27] 2:717. Treby’s marginal shorthand comment is a summary of Hale’s argument: “Upon an occasion H[ale] said that formerly all pleadings were drawn at the bar and then when an exception was made the other did draw it over and amend it at the bar or if he was so peremptory as to send them the demurrer was joined upon that and so the business was all hamērdout at the Bar before it came into pleading but since pleading came all into paper yet the general intention is the same still and demurrers as they were never intended so they must not be made use of to catch men.”

[28] Loveman, 1222, 1224.

[29] 2:51; for Treby’s “post-its” and references to separate sheets and other marks in his Popish Plot Papers at the Derbyshire Record Office, see my “Inside the Commons Committee of Secrecy”, 292.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.