By Cassie Watson; posted 30 March 2025.

According to Robert Shoemaker, quoting an eighteenth-century observer, “the vague legal definition of assault meant that ‘any injury done to a man in an angry insolent manner, be it ever so small, is actionable; for example spitting in his face, jostling him, treading on his toes, or any way touching him in anger.’”[1]

In 1822 J.F. Archbold’s Summary of the Law Relative to Pleading and Evidence in Criminal Cases explained that “An assault is an attempt to commit a forcible crime against the person of another: such as an attempt to commit a battery, murder, robbery, rape, &c.”[2] If a perpetrator were to strike at another but miss, that would be an assault; if they hit the other person, it would be an assault and battery.[3]

By 1861 when the Offences Against the Person Act came into effect, the word assault was not actually defined. Instead, it was used to designate a variety of specific acts that might cause physical harm to another person. It was left up to judges to decide what was meant by ‘harm’. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the word ‘harm’ was typically associated with the effects of physical assault, and so the phrase ‘bodily harm’ was used more regularly than ‘harm’. However, it seems likely that the wider concept implied in today’s usage — encompassing both emotional harm and negligence — was understood. However, if the harm took some other form, for instance disease or mental trauma, an indictment under the 1861 statute could fail.

Where death occurred, the offence shifted immediately to some form of homicide.

Forms of Assault, 1861

The Offences Against the Person Act, which applied to England, Wales and Ireland but not to Scotland,[4] criminalised many specific forms of assault, including:

Some of these categories, particularly those in the top half of the list, imply some sort of judgment on the part of the prosecutor about the nature of the act alleged and the degree to which it caused harm or constituted a battery. According to Peter King, “Victorian legislation tended to formalize changes that had begun more than half a century earlier,”[5] as magistrates began to impose stronger sanctions on those convicted of interpersonal violence. King noted: “This change reflects not only new attitudes to violence but also new attitudes to the manners and reformability of the poor.”[6] But an additional point can be made. Where more than one offence could be alleged — typically attracting a longer or a shorter sentence — jury decision-making can be seen as a marker of wider assumptions about and attitudes to interpersonal violence. That’s still at a level somewhat removed from the mass of the population, but perhaps closer to them than to the magistracy.

What is the ‘Assault Deficit’?

With the exception of the fairly extensive historiography on domestic violence and sexual assault, few studies by legal or crime historians — barring a handful of notable exceptions —investigate forms of non-lethal physical assault in the United Kingdom.[7] Yet, such crimes made up approximately 34% of accusations prosecuted in the Welsh Court of Great Sessions 1730–1830 (around 7,100 individuals), and just under 3.4% of trials (about 7,000) held at London’s Central Criminal Court 1674–1913. The 50–60 years leading up to 1830 is precisely the period Peter King identified as one of significant transformation in attitudes to interpersonal violence.

This graph compares the total number of trials for each of the offence sub-categories listed on the Old Bailey website. About 50% of all trials were for crimes against property; but of crimes against the person, wounding was by far the largest category. Yet the historiography has long focused on forms of homicide. Why? Partly it is related to record survival, since homicide was prosecuted at the assizes and newspapers tended to report violent crimes. Until specific forms of assault were designated as felonies, only murder could incur a death sentence. And many assaults were dealt with as civil matters until the nineteenth century.[8]

Partly it’s to do with interest in the potential explanatory power of Norbert Elias’s theory of the civilizing process, which really exercised crime historians in the 1990s and continues to offer food for thought. In a relatively recent example, Sharpe and Dickinson argued that their study of homicide and violence in eighteenth-century Cheshire provided a “local perspective on the general shift towards ‘polite’ values which has been seen as characterizing the upper and middling social strata of eighteenth-century England.”[9]

This is the ‘assault deficit’: assault was far more common than homicide but has been studied much less extensively. But why does this matter? Some graphs should help to demonstrate the value of studying assault as a means of asking new questions about the past.

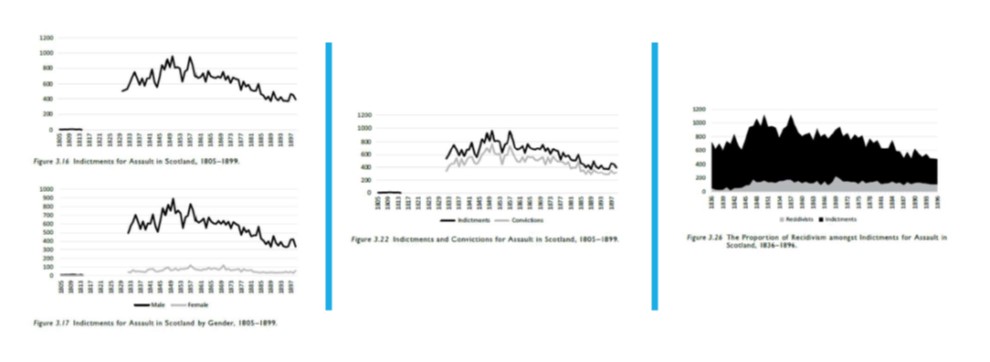

Assault in Scotland, 1805–1899

Assault (considered in its broadest definition) was the most indicted crime of violence in Scotland in the period 1660–1960. Anne-Marie Kilday, for example, tabulated about 33,000 assault convictions in the period 1805–1899, of which 30,000 were males; and about 25,000 assault convictions in the period 1900–1960, of which a vanishingly small proportion was female. These convictions took place in the justiciary courts, but national judicial statistics suggest that in the late 1940s the sheriff courts and juvenile courts combined heard almost the same number of assault cases as the higher courts did: 136 versus 158, respectively, in 1948.[10] But the higher courts heard more cases of sexual assault.

Source: A-M. Kilday, Crime in Scotland 1660–1960 (2019), pp. 125, 127, 128. Reproduced by permission.

Kilday found that interpersonal violence in Scotland between 1660 and 1960 was largely dominated by male assailants and female victims, with motives related to the desire to exert power, control and dominance.[11] While such findings naturally lead to the discussion of domestic violence, the graphs she provides offer additional avenues for exploration.

Apart from the vast over-representation of men among those convicted, it is also worth noting the declining number of male defendants in relation to the relatively static proportion of females indicted during the later decades of the nineteenth century, the consistent ratio between indictments and convictions, and the steady proportion of recidivists among those indicted. All of these trends raise questions not just about gender, which crime historians have long focused on, but also about legal and popular understanding of what constitutes unacceptable violence, access to formal court procedures, desistance from crime, so-called criminal classes, and probably other questions which have both historical and contemporary relevance. When such questions arise we can begin to seek answers to them, taking into account the wider social and cultural trends of the day.

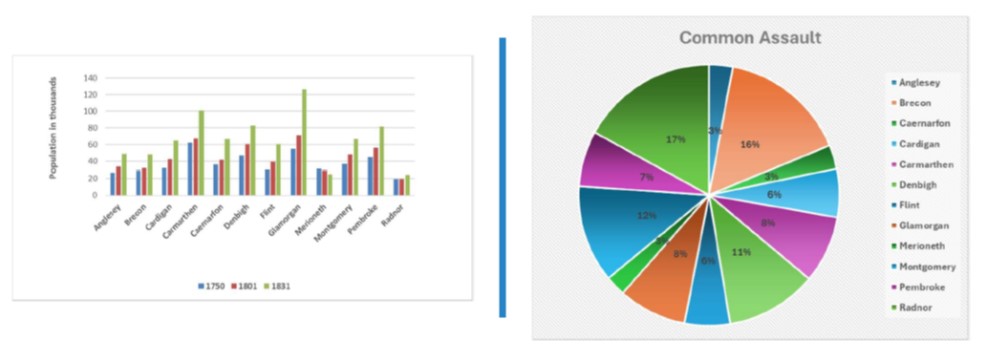

Assault in Wales, 1730–1830

The offences catalogued by the National Library of Wales reveal a disproportionate number of assaults committed in Radnorshire, considering its relatively small population, about 4% of the total for Wales. The same might be said for Brecon. Both were counties in the south of Wales, which suggests regional variations in patterns of violence, or patterns of prosecution. Both are trends worthy of study not just in themselves, but as indicators of wider social attitudes, changes, practices, access to justice, etc.

The population of Wales in 1750 was estimated at about 450,000, rising to 587,245 by 1801. The figures above are absolute numbers which, to be truly meaningful, would have to be broken down by decade in order to show changing patterns in both perpetration / prosecution and conviction; they entirely exclude cases that never approached prosecution. This is part of what makes homicide a better choice for historical study: the chances that a case would not be communicated to the authorities, or actively pursued through the courts, was much lower than for cases of assault, especially common assault. But how much lower is not that easy to determine without more research.

Conclusion

The study of assault, which was highly variable in form, provides valuable insights into socio-legal and popular attitudes to conflict and ‘everyday’ violence, that can serve to add nuance or new findings to those revealed by studies of homicide, which to date has been the most extensively examined form of interpersonal violence. Assault should thus be seen as an important avenue of research by crime and legal historians, and in a future post I will consider ways in which this task might be approached.

Main image: Francisco Goya, The Fight at the Cock Inn, 1777. Museo del Prado. Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Robert B. Shoemaker, The London Mob: Violence and Disorder in Eighteenth-Century England (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2004), 222 and 346n26 citing John Trusler, The London Advertiser and Guide (1786).

[2] J.F. Archbold, A Summary of the Law Relative to Pleading and Evidence in Criminal Cases (London: Pheney, Sweet and Millikin, 1822), 241.

[3] Ibid., 242.

[4] Offences Against the Person Act 1861, 24 & 25 Vict c.100.

[5] Peter King, “Punishing Assault: The Transformation of Attitudes in the English Courts,” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 27, no. 1 (1996): 73-74.

[6] Ibid., 72.

[7] In addition to King, see: Jennine Hurl-Eamon, Gender and Petty Violence in London, 1680–1720 (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2005); Phil Handler, “The Law of Felonious Assault in England, 1803-61,” Journal of Legal History 28 (2007): 183-206; Drew D. Gray, Crime, Prosecution and Social Relations: The Summary Courts of the City of London in the Late Eighteenth Century (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), chap. 5; Anne-Marie Kilday, Crime in Scotland 1660–1960: The Violent North? (Abingdon: Routledge, 2019), chap. 2 & 3; Jo Turner, “The ‘Vanishing’ Female Perpetrator of Common Assault,” in Women’s Criminality in Europe, 1600–1914, ed. M. van der Heijden, M. Pluskota and S. Muurling, 72-88 (Cambridge: CUP, 2020); Katherine D. Watson, Acid Attacks in Britain, 1760–1975 (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023).

[8] King, “Punishing Assault.”

[9] James Sharpe and J.R. Dickinson, “Homicide in Eighteenth-Century Cheshire,” Social History 41, no. 2 (2016): 192.

[10] Criminal Statistics Scotland 1948 (Edinburgh: HMSO, 1949), Table 10, p. 36.

[11] Kilday, Crime in Scotland 1660–1960, 129-130.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.