Posted by Krista J. Kesselring, 22 April 2025.

“Star Chamber proceeding” is now a shorthand for arbitrary and unjust judicial actions masquerading as legal. After the abolition of the court of Star Chamber in 1641, stories spread of its brutally creative punishments, imposed by royal agents after show trials based on charges that had no grounding in the law of the land. Edward Hyde, earl of Clarendon, later recalled that the discretionary power of the king’s councillors acting as judges (“the same persons in several rooms”) meant that in Star Chamber’s final years,

“any disrespect to any acts of state or to the persons of statesmen, was in no time more penal and those foundations of right by which men valued their security, to the apprehension and understanding of wise men, never more in danger to be destroyed.”[1]

Such tales became part of the mythos that helped shore up a commitment to a particular vision of the rule of law and defences against arbitrary power in the centuries after England’s seventeenth-century revolutions. Historians of a past generation sought to show that the storytellers exaggerated and argued that the court was “popular” for much of its history.[2] But the stories had some foundation. Members of the parliament that killed the court after hearing petitioners’ complaints about it certainly thought so: the Act to abolish Star Chamber offered a long list of its failings, summed up in the verdict that it had “undertaken to punish where no law doth warrant, and to make decrees for things having no such authority, and to inflict heavier punishments than by any law is warranted.”[3] So, how did Star Chamber come to its end?

Complaints about the court were varied and longstanding but began to cohere around its lawless discretion from November 1640. Two women helped lay the charges: Sara Burton and Susanna Bastwick petitioned the newly convened parliament for the release of their husbands, Henry and John. The men’s offence? They had published works critical of the king’s religious establishment in defiance of Star Chamber’s decrees regulating the printing press. When they failed to respond to the accusations made against them as Star Chamber’s judges deemed fit, they were treated as having confessed. Their punishment? The court stripped them of their university degrees and licenses to act as ministers, fined them impossible amounts, ordered them to be pilloried and to lose their ears, and sentenced them to imprisonment to last so long as the king pleased. The king’s councillors sent them to prisons outside of England, in Guernsey and the Isles of Scilly, in an effort to deny them the writs of habeas corpus that might otherwise allow them to challenge the legality of their detention. Back when the men were first punished, Susanna had made a point of climbing on a stool to kiss her husband while he stood in the pillory and when his ears were hacked off, she demanded them and carried them away in her handkerchief.[4] She now wrote of the great “want and miseries” of the “many small children depending upon her” to urge parliament to examine the Star Chamber proceedings against John. Sara invoked the “liberties and privileges of this kingdom” in her call to have her husband retrieved from his island prison to make his case. The firebrand member of parliament John Pym brought the women’s petitions to the House of Commons.[5] Within days, petitions from or on behalf of other people punished by Star Chamber came to the Commons, too. The House ordered committees to evaluate individual cases and the “excesses” of the court itself.

The “excesses” alleged by petitioners ranged widely, including the kinds of charges, the nature of the proceedings, the types of punishments imposed, and the ends to which they were put. The court effectively consisted of the king’s council acting in a judicial capacity – executive and judiciary intermixed – and operated without the restraints of common law. It offered a flexibility that had once seemed useful. But lawless discretion ultimately proved dangerous to people, property, and the very polity itself. Part of the problem with Star Chamber lay in the councillors’ use of the court to enforce their own proclamations, orders issued under royal authority alone rather than that of Commons, Lords, and king acting in concert. Proclamations had been a controversial tool of royal power for decades but became increasingly concerning in the years when King Charles ruled without convening parliaments.[6] Among other issues, the king’s agents used proclamations – and heavy fines in Star Chamber for violating those proclamations – to generate revenue for the royal treasury in the absence of parliamentary taxes. And heavy fines became a way to procure indefinite detention at the king’s will if and when the person could not pay, or could not provide the king or his agents something they wanted in exchange for respite. In John Pym’s speeches before the Commons he accused Star Chamber of having become little more than a “court of revenue” and denounced its arbitrary proceedings: law and precedent meant nothing to it.[7]

Alexander Leighton, William Prynne, and John Lilburne were some of the better known victims of the court who petitioned the Commons. They had come before Star Chamber for varieties of unlicensed printing that offended the church establishment, writings the court deemed seditious libel. Leighton and Prynne focused attention on the fact that the bishops who sat on the king’s council and thus also as judges in Star Chamber had a perhaps problematic role in punishing people who criticized them. They also made it clear that “respectable” men were not immune to highhanded treatment and degrading, immiserating punishments. Lilburne made procedure a focus of his complaints about the court. He, too, had first come to Star Chamber for unlicensed printing but the charges kept multiplying, including for insulting the court and its officials when he insisted upon “due process,” which he understood to include rights to put his case before a jury and to refuse to be sworn on oath before knowing the charges against him.[8] Other, lesser known petitioners made their cases to the House of Commons, too. Dorothy Blackborne, for example, complained that the excessive fine in her own case had effectively led to her indefinite detention and the unjust seizure of her family’s property: ten years on, she still suffered in prison, unable to pay for her release despite having exhausted all of her husband’s and son’s resources.[9]

Adding to the petitioners clamouring for justice from the Commons, Sir Richard Wiseman put a petition before the House of Lords in January of 1641 that brought together some of the same concerns and provoked much sympathy. He alleged straight up corruption and bribery among the judges of the court as well as abusive use of their discretionary power. Having lost a case in Star Chamber some years before, he then petitioned the king with a claim that judges had turned the case against him after a generous gift from his opponent. For thus insulting the court, Wiseman found himself dragged back into Star Chamber and sentenced to pay sizable damages to the people insulted as well as an impossible £10,000 fine to the king. The court ordered Wiseman degraded from his knighthood and to have his ears severed. Unable to pay his fine, he languished for years in dire hardship in the Fleet prison. The Lords brought him into their chamber and were shocked by his appearance. Lord Montagu recorded in his journal that Wiseman “moved such compassion in us, especially the poor and beggarly array the man was in, that we fell into speech against the exorbitancy of the court, and chose a special committee to consider the proceedings thereof.”[10] The Lords ordered Wiseman freed and even handed him £50 to cover his immediate need for clothes and food. They charged their new committee to consider not just Wiseman’s case but also the very “institution and power of Star Chamber.”[11]

By early January 1641, then, both Houses had committees to assess the specific cases coming before them and the power of the court itself. At least 47 petitions alleging a variety of injustices from the court came before parliament in the months after Sara Burton and Susanna Bastwick had submitted their own.[12] Whatever concern some of the underlying cases had provoked as they occurred over the previous decade or so, when brought together collectively in the space of a few short months by the petitions to parliament, that concern converted to action. Some petitioners tugged the heartstrings while others provoked anger. Bastwick’s pleas about “tender babes” denied their doting father and Wiseman’s display of the degrading punishments imposed upon gentlemen combined to potent effect. But more than just sympathy and outrage, the petitions prompted talk of the court being both unjust and illegal. “Originalists” of a sort, members spent some time debating whether the court had been created by a statute passed in 1487 that it had clearly exceeded or whether it had a longer, prior history that might warrant some of its seeming excesses. The first bills they brought forward sought simply to regulate the court. But by May, the Commons had embraced the view that the court had been created by statute and decided that the best course was simply to abolish it. They invoked Magna Carta and insisted that the ordinary course of justice and common law of the land must triumph. If the king or his council claimed to have the like authority to imprison by their own warrant again, anyone thereby deprived of their liberty would not “upon any pretence whatsoever” be denied a writ of habeas corpus. By early July, the Lords agreed. The king briefly resisted, but needing funds that parliament judiciously withheld, he grudgingly assented. Whether or not the court had been created by parliament, by parliament it was ended.

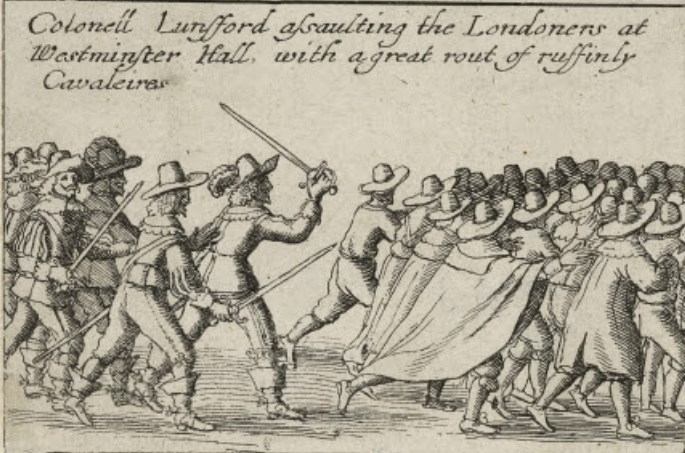

The petitions and protests of a wide variety of people had helped push parliament to act against the “lawless” court. But other grievances remained and the country slid toward civil war. In December 1641, two of Star Chamber’s victims – John Lilburne and Sir Richard Wiseman – led a crowd of Londoners in fighting to defend the parliamentary precinct from an attack by soldiers loyal to the king. Wiseman died in the melee, becoming one of the first “martyrs” for the nascent parliamentary cause.[13]

In January 1649, it was the king’s turn to become a martyr for his own cause, executed upon the sentence of a newly concocted High Court of Justice by the victors in the wars. And Lilburne would soon find that courts answerable to a parliamentary government could be just as arbitrary as those that answered to a king. Much of the revolutionary ferment of these years happened in and about the courts, as people struggled with how best to enshrine the rule of law, rather than lawless discretion. But what shape would this struggle take after the restoration of monarchy in 1660? Would Star Chamber return, too?

Part II: Star Chamber Reborn?

Briefly in 1660-1, members of King Charles II’s first parliament discussed recreating something like the old court of Star Chamber, just with stronger guardrails. One proposal suggested that something of the sort could be useful, if restricted from imposing corporal punishments, excessive fines, or terms of imprisonment longer than two years. But the proposals quietly disappeared, for the moment.[14]

Under King James II, such talk revived, though now focused on expanding the powers of the ancient, common-law court of King’s Bench, a bench filled by judges handpicked by the king and serving at his pleasure. The latterly infamous “Hanging Judge Jeffreys,” chief justice of King’s Bench, read the Act that abolished Star Chamber as having transferred not just its substantive business but also much of its discretionary power to his own court. In the 1685 trial of the notorious perjurer Titus Oates, Jeffreys deemed the punishments laid down by law wholly inadequate to the “exorbitant severity” of the offence and claimed for King’s Bench the old Star Chamber ability to impose a suitably “exemplary punishment upon this villainous perjur’d wretch, to terrify others for the future.”[15] The court ordered Oates flogged over two days and imprisoned for life, with periodic trips out for time in the pillory. Whatever one thought of Oates and his crimes, a punishment unlimited by law did indeed alarm many observers.

The “Glorious Revolution” that ousted King James in 1688 produced a Bill of Rights to bind his successors. Its tenth article held “that excessive bail ought not to be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.” In “The ‘Cruel and Unusual’ Legacy of Star Chamber,” Donald Dripps depicts this article as a direct response to the arbitrary judicial discretion of courts such as Star Chamber and Judge Jeffreys’ King’s Bench. The problem was not so much the particular types of punishments as the ability to impose them excessively, capriciously, and without express legal warrant. This context shaped the later Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution that expanded upon its terms. An “originalist” reading of the Eighth Amendment, Dripps argues, needs to see it as a bar to “arbitrary severity in the quantity or barbarity in the type of punishment, whether inflicted by courts or by legislatures, and whether capital or noncapital.” The Eighth Amendment was meant to condemn “Star Chamber-style discretion” in sentencing. [16]

Whatever the Eighth Amendment should mean to those who apply it in U.S. courts today, Dripps valuably reconstructs the attempt to revive a Star Chamber power under James II and its ending with the Bill of Rights. The constitutional challenges and injustices of one generation evidently can reappear in another, in altered guise, even those associated with a body as infamous as Star Chamber.

Images:

Image 1 is from the copy of Sara Burton’s petition in The National Archives (Kew), SP 16/471, fol. 67d. Image 3 is from John Lilburne, The Tryall of Lieutenant Colonel John Lilburne (London, 1649). Images 2, 4, and 5 come from a series of prints by Wenceslaus Hollar known as the ‘Chronicle of the Civil War’ which appeared under several titles and are here used from the British Museum’s website. The other images come from decks of cards depicting scenes from Restoration-era political controversies and plots, via the British Museum’s website. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

References:

[1] Edward Hyde, earl of Clarendon, The History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England (London, 1707), vol. 1, p. 54; see also p. 223. William Blackstone incorporated this evaluation into his influential Commentaries on the Laws of England (Oxford, 1773), vol. 4, p. 267.

[2] For a survey of this literature, see K.J. Kesselring and Natalie Mears, “Introduction: Star Chamber Matters,” in Star Chamber Matters: An Early Modern Court and its Records, ed. K.J. Kesselring and Natalie Mears (University of London Press, 2021). For an introduction to Thomas Barnes’s extensive work to redeem Star Chamber from the excesses of “Whig” history, see in particular “Star Chamber Mythology,” American Journal of Legal History 5 (1961), 1-11.

[3] 17 Car. I. c. 10, An Act for the Regulating the Privy Council and for taking away the Court commonly called the Star Chamber. For analyses of Star Chamber’s end, see, e.g., H.E.I. Phillips, “The Last Years of the Court of Star Chamber, 1630-41,” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 4th ser., 21 (1939), 103-32, which argues that excessive punishments were the exception not the rule of the court; Daniel L. Vande Zande, “Coercive Power and the Demise of the State Chamber,” The American Journal of Legal History 50.3 (2008-10), 326-49, which endeavours to refute parliament’s accusations against the court and argues that “these accusations are more symptomatic of a severe decline in legitimacy than an outright failure in the administration of justice” (p. 327); and Ian Williams, “Contemporary Knowledge of the Star Chamber and the Abolition of the Court,” in Star Chamber Matters: An Early Modern Court and its Records, ed. K.J. Kesselring and Natalie Mears (University of London Press, 2021), 195-215, which does not try to argue that MPs were wrong to close the court but examines why they did, emphasizing the confluence of popular and professional complaints about the role of bishops in the court. Also useful is Steven Carl Dalla Lana’s MPhil thesis, “The Court of Star Chamber, 1629-1641” (University of St Andrews, 1987), which examines the petitions filed against the court in the Long Parliament.

[4] The Earl of Strafford’s Letters and Despatches, ed. William Knowler and George Radcliffe (London, 1739), vol. 2, p. 85, cited in Vande Zande, “Demise,” 344.

[5] The National Archives, Kew, State Papers Domestic, Charles I: SP 16/471, fols. 67-67d, 69 for the petitions. For the story of the renditions to the Channel Islands to avoid habeas corpus, see in particular David Cressy, England’s Islands in a Sea of Troubles (Oxford University Press, 2020), ch. 11 and on the struggle to have habeas pertain throughout the king’s dominions, see Paul Halliday, Habeas Corpus: From England to Empire (Harvard University Press, 2010).

[6] For earlier controversy about proclamations, see, e.g., Esther S. Cope, “Sir Edward Coke and Proclamations, 1610,” The American Journal of Legal History 15 (1971), 215-21 and also J.P. Kenyon, ed., The Stuart Constitution, 1603-1688: Documents and Commentary (Cambridge University Press, 1966), p. 119.

[7] Kenyon, ed., The Stuart Constitution, pp. 202, 205.

[8] On Lilburne, see M.J. Braddick, The Common Freedom of the People: John Lilburne and the English Revolution (Oxford University Press, 2018). On the proceedings against him and the others, see Dalla Lana, “Star Chamber.”

[9] Parliamentary Archives, HL/PO/JO/10/1/46, petition of Dorothy Blackborne.

[10] Historical Manuscripts Commission, Report on the Manuscripts of the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry, K.G., K.T., Preserved at Montagu House, Whitehall, III. VI. The Montague Papers: Second Series (London, 1926), p. 405; cited in Dalla Lana, “Star Chamber,” 56-7.

[11] Parliamentary Archives, HL/PO/JO/1/46, Main Papers (1 Jan 1641-12 Jan 1641); Lords Journal, 4:124. Dalla Lana, “Star Chamber,” ably reconstructs the Wiseman episode, pp. 56, 96-8.

[12] Dalla Lana, “Star Chamber,” 73.

[13] See the contemporary published memorials: London’s Teares, upon the Never Too Much to be Lamented Death of our Late Worthie Member of the House of Commons, Sr Richard Wiseman (1642); The Apprentices Lamentation, together with a Dolefull Elegie upon the Manner of the Death of that Worthy and Valorous Knight, Sr Richard Wiseman (1641); and A Bloody Masacre Plotted by the Papists (1641).

[14] Dalla Lana, “Star Chamber,” 101-3.

[15] Jeffrey’s speech was printed at the time in Richard Sare, The Tryals, Convictions & Sentence of Titus Oates upon Two Indictments for Willful, Malicious, and Corrupt Perjury (1685), pp. 58-9, and is reprinted in Donald A. Dripps, “The ‘Cruel and Unusual’ Legacy of the Star Chamber,” Journal of American Constitutional History 1 (2023), 139-229, at 165-66 and 222-24. As Dripps notes (p. 165), Jeffreys authorized the publication.

[16] Dripps, “The ‘Cruel and Unusual’ Legacy of the Star Chamber,” 143, 144. See also Lois G. Schwoerer, The Declaration of Rights, 1689 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981).

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

[…] Lord Montagu wrote that Wiseman “moved such compassion in us, especially the poor and beggarly array the man was in, that we fell into speech against the exorbitancy of the court, and chose a special committee to consider the proceedings thereof.” […]

LikeLike