Guest post by Susannah Wilson, 20 November 2025.

A Murder in Midsummer

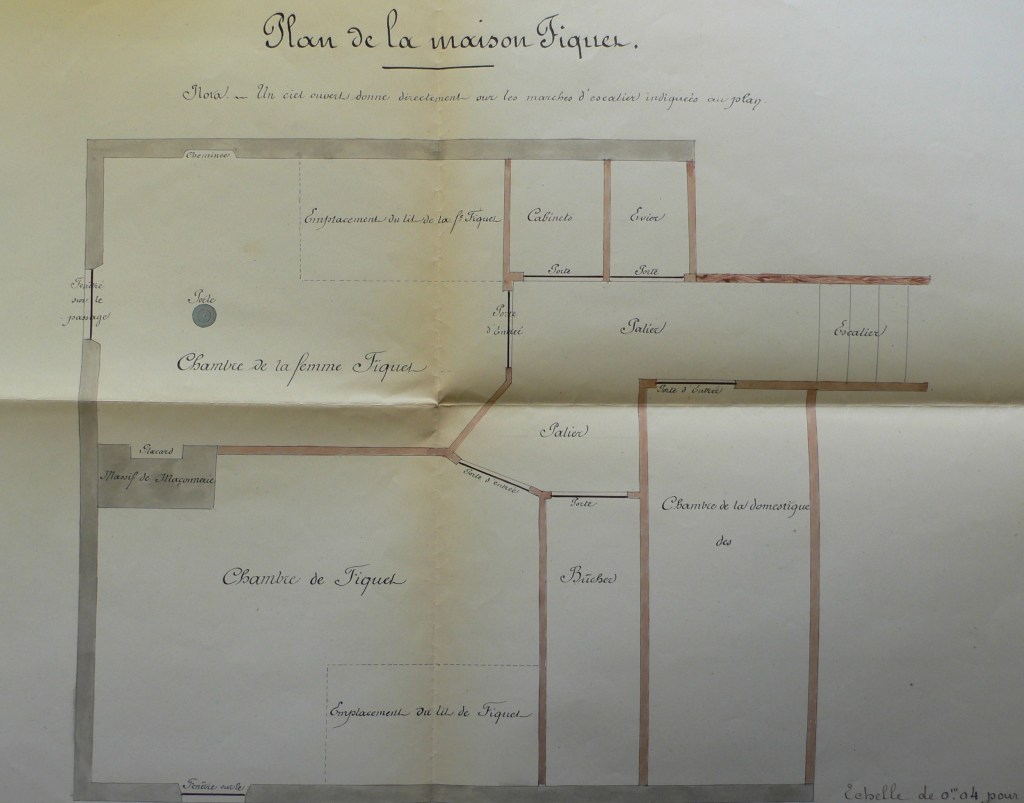

In the summer of 1882, an unusual and shocking crime unsettled the residents of Dijon, a small industrial city in eastern France. Acting in plain sight, a woman named Marie-Françoise Fiquet lured five-year-old Henriette Barbey away from the gates of a city nursery school and took her to a small apartment in the city centre (Fig. 1). What happened between the child’s abduction at midday and the discovery of her body the following morning on the banks of the Canal de Bourgogne (Fig. 2)—the city’s main industrial waterway—remains a mystery.[1]

The perpetrator was a poor worker who had been employed at the city’s tobacco factory, a major employer of women in Dijon during the 1880s. Investigators soon discovered that she had a notorious local reputation and was widely suspected by neighbours and acquaintances of having attempted to poison her husband, and other vulnerable people who had crossed her path.

Morphine Addiction and Criminal Responsibility

The case against Marie-Françoise Fiquet hinged not on proving she had caused the death of Henriette Barbey, but on determining the extent of her criminal responsibility and uncovering a motive. Initially, Fiquet was arrested alongside her husband, and both were charged with “assassinat”—murder with premeditation. At first, the case appeared clear-cut, supported by witness testimony placing the couple with the child.

However, investigators soon discovered that Madame Fiquet was a morphinomane (a medical morphine addict) who routinely stole money and deceived others to obtain her drug. She claimed that her judgment had been impaired by morphine use and that she was suffering withdrawal at the time of the murder because her syringe was being repaired. The investigation found the latter claim to be true.

Although opium had been used as an analgesic throughout the nineteenth century—and indeed for centuries before—morphine was still relatively new in 1882. Following its synthesis and the invention of the hypodermic syringe in the 1850s, morphine entered mainstream medical practice in the 1870s, regulated only by pharmaceutical laws intended to restrict access to poisons.[2] Most morphine users, like Fiquet, were introduced to the drug by physicians; the growing addiction crisis was fuelled by the exploitation of repeat prescriptions by unscrupulous pharmacists.[3]

Uncertainty about morphine’s influence on mental faculties became evident during the Fiquet trial. Addiction was not considered sufficient to excuse the crime, nor was it viewed as evidence of broader psychological disturbance. On the contrary, forensic medical experts argued that morphine had a regulatory effect, in all likelihood calming rather than aggravating homicidal impulses.[4] This interpretation was ultimately sidelined as a causal explanation, yet the police investigation uncovered evidence suggesting that the child had been sedated with morphine. This emerged during interrogations, when Madame Fiquet hinted that the child might have “accidentally” ingested sugar-water laced with morphine, prepared for her own use.

A Motiveless Crime?

The official autopsy concluded that the cause of Henriette’s death was drowning; her head appeared to have been submerged in water. The report noted that she had eaten cherries shortly before her death, but no trace of morphine was detected in her stomach, though the analyses were inconclusive. The absence of a clear motive made the crime all the more perplexing. Why would a woman, herself a mother, abduct and kill another child?

During interrogations, Marie-Françoise Fiquet repeatedly claimed she had acted under an irresistible impulse. At times, she spoke of being guided by spirits, yet she could offer no coherent explanation for her actions. Testimony from other witnesses revealed a long history of trauma and disturbed behaviour. Fiquet’s first child, born when she was just sixteen and unmarried, died before the age of one; her second child, Marie-Louise, survived. In the years that followed, Fiquet sought medical treatment in hospitals across the region, often for vague and undefined ailments. Psychiatrists Dr Émile Blanche and Dr Marandon de Montyel, tasked with assessing her mental state after her arrest, concluded that she was a “simulator” and an attention-seeker.

Her troubled history revealed that during a period of self-medication with laudanum, another child was born and either died or was killed under mysterious circumstances. Madame Fiquet had asked her niece to dispose of the body of an infant in the river nearby, just as Henriette would be abandoned by the canal. After this, Fiquet exhibited obsessive behaviour surrounding childbirth, medical procedures, and infant loss. She aspired to become a midwife but was rejected from training due to her unreliability. Undeterred, she impersonated a midwife and cultivated relationships with vulnerable pregnant women to gain access to their babies. She even told her husband that, during his absence, she had given birth to twins who had died—a fantasy that led the couple to ritually visit the graves of twins who were not theirs. Fiquet had intended to “adopt” these infants, born to an unmarried mother, whose deaths were also shrouded in mystery.

Madame Fiquet’s macabre and ritualistic behaviour echoed that of other notorious figures, such as Amelia Dyer, the English “baby farmer” executed in 1896, and French woman Victoire Vesseyre, convicted of killing infants in her care in 1867.[5] Similarly, Constance Thomas—the infamous ”femme des Batignolles”—was convicted in 1891 for performing thousands of clandestine abortions after reportedly losing her own cherished infant.

These losses were poorly understood as motivating factors in Fiquet’s crime. Her fixation on administering medicines to herself and others, including children, suggests that Henriette’s abduction was the culmination of some type of longstanding psychological disturbance. The “urge” Fiquet described appears to align with what would later be classified as a factitious disorder—Munchausen syndrome and its variant, Munchausen by proxy. Such disorders often stem from a compulsion to control uncontrollable events, such as life and death, and are frequently linked to personal trauma.[6]

Poisoning as Intimate Violence

Even today, in the twenty-first century, when a child is deliberately harmed by a female caregiver or proxy, society is profoundly shaken by the breach of trust it represents. Such women—often sensationalized as “angels of death”—rarely receive leniency, as their actions violate deeply ingrained assumptions about gendered human nature. As forensic psychologist Anna Motz observes, “the reality of women’s violence is a truth too uncomfortable to take seriously: a taboo that offends the idealized notion of women as sources of love, nurture and care.” [7]

Marie-Françoise Fiquet and her husband Pierre were tried by jury at the Côte-d’Or assises court, with a verdict delivered on 8 March 1883. Pierre was acquitted of all charges; he was thought a “semi-idiot” and prosecutors and public opinion agreed that he had not masterminded the crime but had been swept along by his wife’s behaviour. Crucially, he had not been present when the child died. Marie-Françoise, however, was considered intelligent and competent. She was found guilty of murder, with extenuating circumstances attributed to her drug addiction and psychological instability. Spared the guillotine, she was sentenced to twenty years of hard labour. Because French women were rarely sent to penal colonies (the government preferred to send younger women), she likely served her sentence in France.[8] Her conviction halted what appeared to be an increasingly lethal trajectory. Her fate remains unknown, though given her poor health, it is probable that she died in prison.

Author bio: Susannah Wilson is a Reader (Associate Professor) in French Studies at the University of Warwick interested in the connections between cultural history, women’s lives, the French psychological sciences, crime, and writing the self.

Images:

Banner image: Edouard Couturier, Les Filles-Mères, cover of L’Assiette au Beurre, no. 89, 13 December 1902. Public domain, BNF Gallica.

Figure 1: Interior plan of the Fiquet family apartment at 10 rue Musette. Archives Départementales de la Côte-d’Or, Dijon. Author’s photograph; used by permission.

Figure 2: Police map of the Canal de Bourgogne showing the location of the body. Archives Départementales de la Côte-d’Or, Dijon. Author’s photograph; used by permission.

Notes:

[1] Details about the case are taken from my book, A Most Quiet Murder: Maternity, Affliction, and Violence in Late Nineteenth-Century France (Cornell University Press, 2025).

[2] Thomas Dormandy, Opium: Reality’s Dark Dream (Yale University Press, 2012), 120; Howard Padwa, Social Poison: The Culture and Politics of Opiate Control in Britain and France, 1821–1926 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 40-41.

[3] Jean-Jacques Yvorel, “La loi du 12 juillet 1916,” Les cahiers dynamiques 56, no. 3 (2012): 128-133; Virginia Berridge, Opium and the People: Opiate Use and Policy in Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century England (Free Association, 1999), 239-42. See also Jean-Jacques Yvorel, Les poisons de l’esprit: Drogues et drogués au XIXe Siècle (Quai Voltaire, 1992), 237-241; Emmanuelle Retaillaud-Bajac, Les paradis perdus: Drogues et usagers de drogues dans la France de l’entre-deux-guerres (Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2009), 10-11.

[4] Sara Black, “Morphine on Trial,” French Historical Studies 42, no. 4 (2019): 623-653 (628-30).

[5] Ruth Ellen Homrighaus, “Baby Farming: The Care of Illegitimate Children in England, 1860–1943,” PhD diss., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2003, 1-2; Odile Krakovitch, Les femmes bagnardes (O. Orban, 1990), 9-12.

[6] On different views on the causes of factitious disorder, see Richard A. A. Kanaan and Simon C. Wessely, “The Origins of Factitious Disorder,” History of the Human Sciences 23, no. 2 (2010): 68-85 and Caroline Eliacheff, “Le syndrome de Münchausen par procuration psychique,” Figures de la psychanalyse 2, no. 12 (2005): 149-164.

[7] Anna Motz, A Love That Kills: Stories of Forensic Psychology and Female Violence (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2023), 4.

[8] Krakovitch, Les femmes bagnardes.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.