Guest post by Helen Rutherford, 11 December 2025.

In The National Archives at Kew is a water-damaged, grubby, but intriguing atlas. It is a large volume and its coloured endpapers frame pages of hand-annotated maps, each one delineating the boundaries within which Victorian coroners held sway over the investigation of sudden and suspicious deaths. Catalogued as part of the ‘Home Office: Coroners and Criminal Law: Correspondence and Papers’ at HO 84/3, this volume is likely to be unique: the only surviving comprehensive cartographic record of how death investigation was organised in England and Wales at the turn of the twentieth century.[1] Why would the Home Office need such detailed maps? The answer reveals a hidden geography of Victorian administration, where death required not just investigation but precise territorial demarcation.

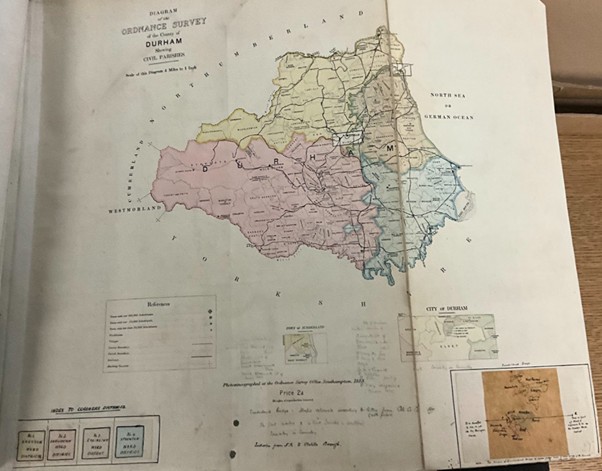

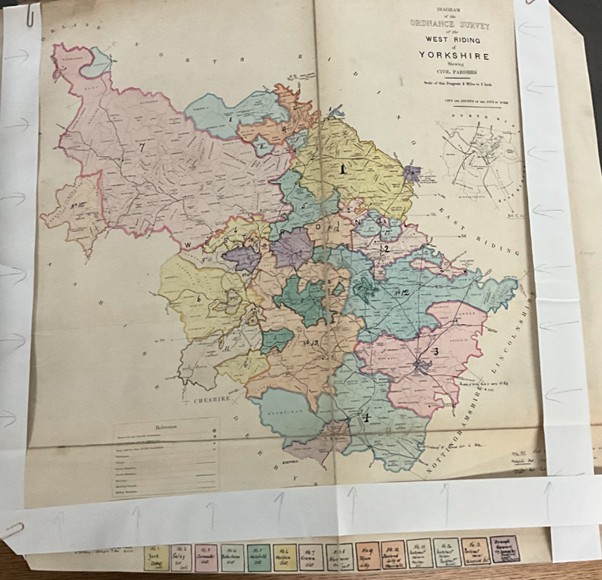

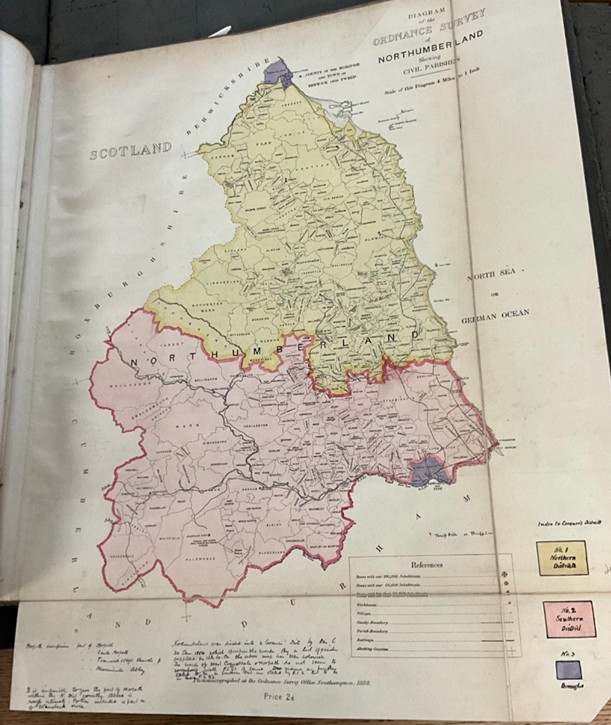

This atlas, produced between 1888 and 1902 using Ordnance Survey maps, was probably compiled following the introduction of the Coroners Act 1887, the first significant attempt to consolidate centuries of accumulated coronial law.[2] The atlas covers only England and Wales; Scotland’s different system of death investigation through the Procurator Fiscal meant it had no need for coronial districts. These maps were essential tools in navigating the complex patchwork of English and Welsh jurisdictions that had evolved since medieval times.

A Working Document’s Biography

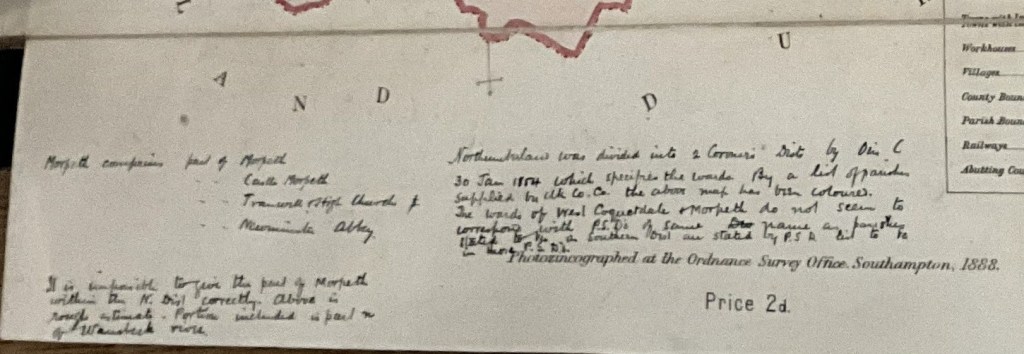

The physical condition of HO 84/3 speaks to its life as a working document rather than a showpiece. The cover is water-damaged and dog-eared and stains mar several pages, suggesting hasty consultations in less-than-ideal conditions. Grubby smudges indicate frequent handling by multiple users. Some pages are torn and repaired. Yet despite, or perhaps because of, this wear, the atlas possesses a particular beauty. The boundaries and shaded areas, in pastel water colour of pink, yellow, purple, blue, orange and sometimes green, create a rainbow geography of death investigation. Careful annotations in what appears to be the same hand record amendments, clarifications, and occasional puzzlement at particularly complex boundaries.

The maps themselves represent cutting-edge Victorian technology. Produced by the Ordnance Survey Office in Southampton using photozincography, commercially known as ‘zinco’, they demonstrate the drive to make accurate cartographic information both reproducible and affordable.[3] At two pence per map (marked prominently), these were tools for everyday administration rather than luxury items. Some pages bear an official stamp reading ‘Ordnance Map Depot, Whitehall Press, Map Department 15 Charing Cross 8 W’, marking their journey through government offices. The Durham map features a brown-paper patch pasted in the bottom right-hand corner, offering a detailed close-up of a particularly troublesome boundary: a pragmatic solution to cartographic complexity.

The binding by Waterlow and Sons Limited, a prominent printing firm, suggests official commissioning rather than ad hoc compilation.[4] The progression from Bedfordshire through to Yorkshire’s West Riding (with its fourteen separate coroners’ districts) and then through Welsh counties from Anglesey to Radnorshire reveals systematic organisation. Some maps, like Leicestershire’s, show evidence of updating: a revised version from 1902 has been inserted to replace an earlier iteration, suggesting the atlas remained in active use into the Edwardian period.

The Coroners Act 1887

Understanding this atlas requires grasping the effort to consolidate the law on coroners in the Coroners Act 1887. Before this consolidation, coronial law reflected a medieval inheritance that had been tinkered with throughout the nineteenth century.[5] The Municipal Corporations Act 1835 mandated that Boroughs should appoint their own coroners, often redrawing old county boundaries. Some counties maintained their ancient coroners, elected under the county franchise, but numerous borough coroners, elected by local town councils, oversaw the new industrial conurbations. Within the large coroner districts, many liberties, honours, and franchises continued to exist. Ancient ecclesiastical liberties maintained coronial rights dating back centuries. The City of London had its own coroner, distinct from those serving surrounding Middlesex. Some coroners were full time appointees dealing with hundreds of inquests each year and others were part-time office holders, rarely called upon.

The 1887 Act attempted to rationalise the law relating to coroners without entirely sweeping away its historical foundations. The atlas captures this moment of transition, recording both the administrative reality and, through its historical notes, the complex evolution that preceded it. The Northumberland map includes a chronology of boundary changes. The West Riding of Yorkshire’s fourteen districts reflect the county’s size but also its industrial intensity of towns such as Leeds, Bradford, Sheffield, Wakefield, Huddersfield, and Doncaster: the mills and mines generated work requiring multiple coroners to investigate.

Coroners needed to reach death scenes quickly, summon juries from the neighbourhood, and understand local conditions. The atlas reveals the landscape they had to operate within. Each coloured boundary represents a balance between history, geography, and administrative efficiency.

The Missing Piece

My research into nineteenth-century legal history in North East England has revealed coroners as crucial yet understudied figures in Victorian society.[6] They stood at the intersection of medicine and law, local knowledge and state power, community justice and professional expertise. Yet their records remain frustratingly scattered. Some survive in local archives, carefully preserved by historically-minded successors. Others lurk within assize files, retained only when inquests led to criminal trials.[7] I recently discovered boxes of coronial records for parts of Yorkshire at The National Archives that remain wrapped, sealed and unopened, like Christmas parcels: testimonies to deaths investigated but histories unexplored.

This archival scatter reflects coroners’ ambiguous position in Victorian administration. Unlike judges or magistrates, coroners operated quasi-independently, often maintaining private practices as doctors or solicitors alongside their official duties. Their records occupied a similar liminal space: official documents yet personal property, public proceedings yet private papers. The 1887 Act was part of a drive to professionalise and standardise the coronership, but this process took decades: and, despite the Coroners and Justice Act 2009, arguably, is not yet complete.

The atlas provides a framework for understanding this scattered archive. By mapping jurisdictions, it reveals which coroner would have investigated deaths in any given location. For researchers tracking industrial accidents in Manchester’s mills or suspicious deaths in London’s rookeries, the atlas offers essential orientation. More broadly, it enables comparative studies. How did urban and rural districts differ in their organisation? What can boundary changes tell us about Victorian England’s transformation?

Reading the Maps

Close examination of individual maps reveals stories beyond administrative boundaries. The hand annotations throughout suggest ongoing negotiation and clarification: boundaries that looked clear on paper proved fuzzy in practice.

Urban areas presented special challenges, visible in the maps’ varying scales and detail levels. London’s numerous coronial districts required larger-scale maps to remain legible, whilst rural counties could be represented at smaller scales. The contrast between the West Riding of Yorkshire’s fourteen districts and smaller counties’ single jurisdictions illustrates how industrialisation and urbanisation transformed death investigation from occasional duty to full-time occupation.

Technologies of Knowledge

The atlas represents multiple technologies converging to create new forms of administrative knowledge. Photozincography made accurate map reproduction affordable, enabling widespread distribution of standardised geographical information. The Ordnance Survey’s systematic mapping of Britain provided the base layer of geographical truth. Colouring and annotation added the administrative overlay, transforming general geography into specialised legal cartography.

This technological sophistication served a deeply human purpose. Each boundary encompassed communities grieving unexpected losses, families seeking answers about suspicious deaths, workers demanding investigation of industrial accidents. The coroner within these mapped boundaries brought state authority to local tragedy, translating individual death into administrative category: accident, suicide, murder, or natural causes (sometimes ‘Visitation of God’).

The atlas’s working life, evidenced by its water damage and worn pages, suggests frequent consultation. Who used it? Home Office clerks determining jurisdictional disputes? Legislators contemplating statutory change? Lawyers seeking the appropriate coroner for a client’s case? Each consultation represented a moment when abstract boundaries met concrete tragedy, when administrative geography shaped human experience of death and justice.

An Atlas for Everyone

Standing in The National Archives’ map room, at the 2025 Legal Records Jamboree where I spoke about the atlas, looking through HO 84/3, I’m struck by its democratic comprehensiveness. Every parish in England and Wales appears within its boundaries. Whether investigating a farm labourer’s death in rural Norfolk or a factory worker’s demise in industrial Liverpool, the appropriate coroner’s area could be identified. This universality reflects the coroner’s unique position in English law: the official who might investigate anyone’s death, from pauper to peer.

The atlas invites multiple readings. Local historians can trace their area’s coronial boundaries, perhaps explaining why certain records survive in unexpected archives. Social historians might correlate coronial districts with mortality statistics, industrialisation patterns, or demographic change. Legal historians can use it, alongside the judicial returns, as the foundation of an investigation into the effects of the 1887 Act.

For my research into nineteenth century legal history, the atlas provides both specific information and methodological inspiration. It demonstrates how administrative documents can illuminate social history, how technical records preserve human stories, how bureaucratic tools reveal state–society relationships. The unnamed Victorian hand that carefully annotated these maps left traces of administrative practice that no legislation or policy documents capture.

Conclusion: Territories of Death

The Coroners’ Districts Atlas of England and Wales is more than a cartographic curiosity. It represents a moment when the Victorian state attempted to rationalise medieval inheritance, when modern administrative imperatives met ancient local customs, when death investigation became systematic. The 1887 Act that prompted its creation began the long transformation of the coronership from ancient office to modern profession.

Yet the atlas reminds us of continuities. The boundaries it records often followed ancient parish limits, hundred borders, and county divisions dating back centuries. The coroner investigating a suspicious death in 1890s Cumberland was grounded in territories shaped by Viking settlements, Norman conquests, and Tudor reorganisation. Modern death investigation operated within ancient geographical imagination.

Today, as we grapple with our own administrative challenges (pandemic response, environmental crisis, technological transformation), the atlas offers perspective. The Victorians too faced the challenge of organising state response to individual tragedy, of balancing local knowledge with central coordination, of making death legible to bureaucracy whilst respecting human grief. Their solution, mapped in careful detail across HO 84/3’s pages, illuminated territories of death investigation that shaped how England and Wales organised the legal processes around sudden death for generations.

For researchers, the atlas offers both a practical tool and a conceptual framework. It assists us to locate specific coronial records and trace administrative evolution. But it also invites us to think spatially about law, to recognise how geography shapes justice, to understand that every legal decision happens somewhere specific. The coroner’s verdict, pronounced in a pub or purpose-built coroner’s court, gained authority partly from occurring within properly mapped boundaries.

This is ‘an atlas for everyone’: every location, every community, every death properly assigned to its appropriate investigator. In mapping coronial districts, the Victorian state mapped its ambitions for comprehensive, systematic, and geographically organised justice. The atlas captures a system whose imperfections were apparent, making it valuable as historical evidence of the coronial system in transition.[8] In its worn pages and annotations, we see the Victorian state as a human endeavour attempting to bring order to the disorder of unexpected death.

—–

Author Bio: Dr Helen Rutherford is an Associate Professor and solicitor (non-practising) at Northumbria University’s School of Law, specialising in nineteenth-century legal history in North East England. She is currently compiling a volume of primary sources on Victorian coroners for Routledge.

Images: All images © the author, used by permission from The National Archives, HO 84/3, Coroners’ Districts of England and Wales, c.1888–1902. Crown copyright images reproduced under Open Government Licence v3.0.

Banner image: The atlas cover showing water damage and wear.

Notes:

[1] The National Archives, HO 84/3, Coroners’ Districts of England and Wales, c.1888–1902.

[2] Coroners Act 1887 (50 & 51 Vict. c. 71).

[3] For more on Ordnance Survey maps and Photozincography see W. A. Seymour, A History of the Ordnance Survey (Folkestone: Dawson, 1980); Geoffrey Wakeman, Aspects of Victorian Lithography, Anastatic Printing and Photozincography (Wymondham: Brewhouse Press, 1970), 43-53.

[4] For more on Waterlow and Sons see Chris Waterlow, The House of Waterlow: A Printer’s Tale (Market Harborough: Troubadour Publishing, 2013).

[5] For a short history see the website of the Coroners Society (accessed 8 December 2025).

[6] Helen J. Rutherford, “The Coroner and the Medical Profession in Victorian Newcastle Upon Tyne: ‘… Antagonism and Offence Towards the Medical Profession Such as has Rarely Been Exhibited,’” Northern History 60, no. 2 (2023): 203-226.

[7] For a useful source of information about the preservation of coroners’ records see Jeremy Gibson and Colin Rogers, Coroners’ Records in England and Wales (Manchester: Federation of Family History Societies, 1997).

[8] Despite the attempt at codification of the law in the Coroners Act 1887, it was recognised by the authorities and the public that the coronial system was not fit for purpose. In 1908 the Chalmers Committee reported its findings in the First Report of the Departmental Committee appointed to inquire into the Law relating to Coroners and Coroners’ Inquests, and the Practice in Coroners’ Courts. Parliamentary Papers, 1909, Cd. 4782, vol. XV. This report eventually led to wider reform and the Coroners Act 1926.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.