By Cassie Watson; posted 26 December 2025.

In the wake of the Thames Torso Murders (1887–89), the Jack the Ripper killings of autumn 1888, and several subsequent unsolved murders that were thought possibly to be the work of the Ripper,[1] the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, James Monro, tried to convince the Home Office to pay more for specialist medical reports in homicide cases. Monro was already in dispute with the Home Office about financial matters including staffing, quality of uniforms, pay and pensions.[2] To that mix he added a request, circulated on 19 September 1889 by the Chief Surgeon to the Metropolitan Police, Dr Alexander O. MacKellar (1845–1904), that “Divisional Surgeons in all cases of Murder or Manslaughter to send a report of their post-mortem examination, and conclusions as to the cause of death of the person killed, with as little delay as possible to the Commissioner.”[3] This was the opening salvo in a short-lived dispute between the Met and the Home Office that, ultimately, the police won.

Fair Fees for Special Reports

The records of this dispute, preserved in The National Archives,[4] show that the series of mysterious murders in 1887–89 led Monro to conclude that “experience has shown the necessity of police having the earliest possible information as to the medical examination in such cases and that it is advisable to establish a uniform practice in the matter.”[5] He realised that the normal fee would not suffice and asked for MacKellar’s opinion, which was given in early January 1890:

“I would strongly advise that these fees be treated as ‘special fees’, each case to be considered according to its merits and importance. A careful microscopical examination of blood or seminal stains on clothing or the investigation of a ‘Whitechapel murder’ would naturally require a much higher rate of remuneration than a report expressing the opinion that a child was still-born (this latter case would probably in many instances be well remunerated by a fee of 10s.6d.).”[6]

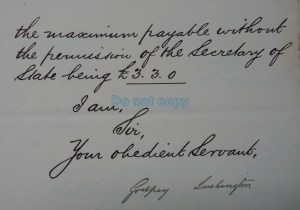

But the Home Office, who had to approve all Met Police expenditure, balked at the potential cost, and in March 1890 its permanent under secretary of state (1886-95), Godfrey Lushington (1832–1907), told Monro that the “maximum payable without the permission of” the Secretary of State would be 3 guineas (the normal fee for an autopsy report delivered to an inquest was 2 guineas) and that the inquest verdict had to be in.[7] In April 1890 Monro was told to keep “a careful account … of cases in which a report is asked for under this authority.”[8]

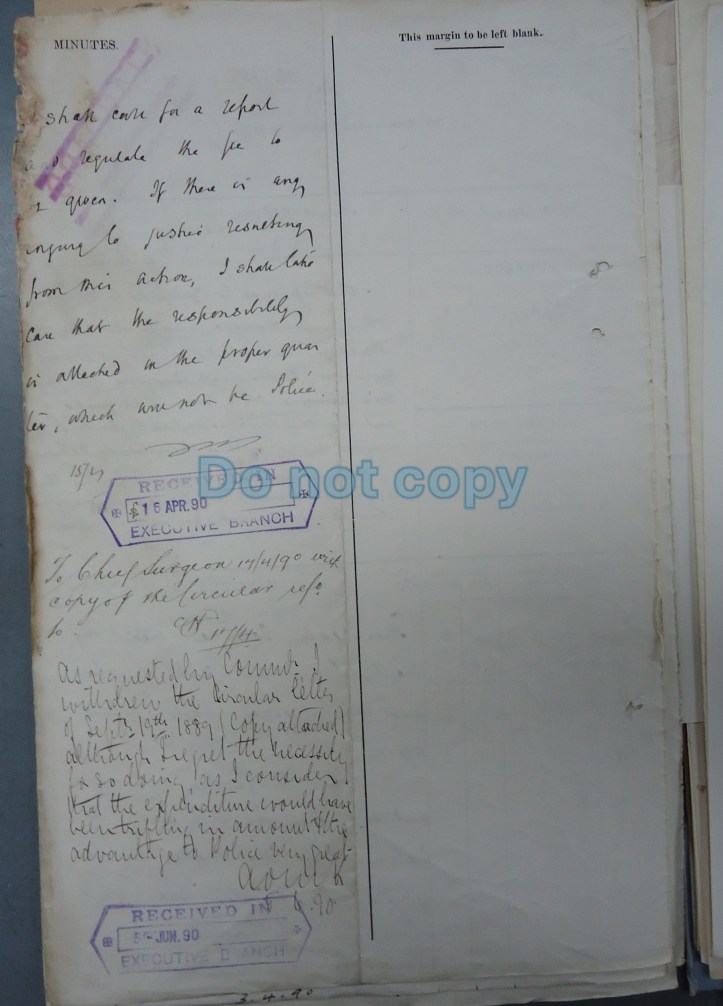

By June Monro’s frustration with the Home Office, Home Secretary and Receiver (the Met Police’s chief financial officer) was clearly visible in the comment noted on this document: “This again does not meet my wants, but I am sick of referring this question back and back again.”[9] MacKellar was instructed to withdraw the order that had been issued in September, and Monro decided that “In any important cases I shall call for a report and regulate the fee to be given. If there is any injury to justice resulting from this action, I shall take care that the responsibility is attached in the proper quarter, which will not be Police.”[10] MacKellar was unhappy about this (“the expenditure would have been trifling in amount and the advantage to Police very great”),[11] and Monro resigned on 18 July 1890; but it was they who had the last word.

The Home Office had agreed that “special cases” merited increased fees to medico-legal experts, so although routine cases were not dealt with by specialists, any case of murder or rape that seemed to pose practical forensic problems was thereafter tackled by recognised experts who were paid more — by the turn of the century a lot more — than the police surgeons who carried out post-mortem exams in more routine cases.[12] The ‘careful accounts’ that the police kept show that in 1897, for example, the highly reputed forensic expert Thomas Bond was earning considerably more than other police surgeons in London.[13]

Conclusion

Since the Metropolitan Police was under the direct authority of the Home Secretary from 1829 to 2000, the correspondence exchanged between police and government officials provides a unique paper trail stuffed full of fascinating detail (and the occasional irate comment) concerning matters of cost, management, and procedure. I have used these documents to identify discussions and decisions related to the cost of medico-legal work in London, so would note in conclusion that if similar debates were held in other parts of the country, as indeed they must have been,[14] the discovery and publication of such records would provide a great deal of interesting, useful information to historians of policing, medicine, crime and ‘forensics’.

Images

Main image: A major discussing medicine with two doctors. Wood engraving after George du Maurier (1834-1896), n.d. Source: Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

Caricature of James Monro (1838-1920) by Spy (Leslie Ward), published in Vanity Fair, 14 June 1890. This version from the City College of New York collection, via Wikimedia Commons.

Photograph of Dr Thomas Bond (1841-1901), via Wikimedia Commons.

Images from MEPO 2/229: Metropolitan Police: Office of the Commissioner: Correspondence and Papers. Divisional Surgeons: Post-mortem examinations fees, 1889–1900 © the author, used by permission from The National Archives. Crown copyright images reproduced under Open Government Licence v3.0. Images not to be copied.

References

[1] The Poplar Murder — the killing of Rose Mylett in Clarke’s Yard, off Poplar High Street on 20 December 1888, is mentioned. Both MacKellar and Monro refer explicitly in this document series to the Whitechapel killings; MacKellar was present at the post-mortem on possible Ripper victim Alice McKenzie in July 1889. It seems both were concerned that Jack the Ripper would start killing again.

[2] M. C. Curthoys, “Monro, James (1838–1920), police officer,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23 Sep. 2010); Accessed 26 Dec. 2025. https://www-oxforddnb-com.oxfordbrookes.idm.oclc.org/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-97913.

[3] The National Archives (hereafter TNA) MEPO 2/229, Circular from Chief Surgeon to Divisional Surgeons, 19 September 1889.

[4] TNA MEPO 2/229: Metropolitan Police: Office of the Commissioner: Correspondence and Papers. Divisional Surgeons: Post-mortem examinations fees, 1889–1900. This series formed the basis of my presentation at the 2025 Legal Records Jamboree, where another document of interest to historians of death investigation was presented: see the recent post by Helen Rutherford.

[5] TNA MEPO 2/229, Memo from the Commissioner to the Chief Surgeon, 13 September 1889, Subject: Medical Special.

[6] TNA MEPO 2/229, Minutes: MacKellar, 4 January 1890, in response to Monro’s query of 18 October 1889.

[7] TNA HO 45/9711/A51187, Note by Godfrey Lushington, 18 February 1890; reiterated in MEPO 2/229, Home Office A51.187, 25 March 1890.

[8] TNA MEPO 2/229, Home Office A61.187/2, Subject: Medical, 12 April 1890.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Katherine D. Watson, Medicine and Justice: Medico-legal Practice in England and Wales, 1700–1914 (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020), 226-232.

[13] TNA MEPO 2/229, Return of fees paid to divisional surgeons for post-mortem examinations and special reports thereon during the year ended 31st March 1897.

[14] See for example Angela M. Buckley, “The Science of Sleuthing: The Evolution of Detective Practice in English Regional Cities, 1836–1914,” unpublished PhD thesis, Oxford Brookes University, 2023. She notes many references to costs, which were evidently of concern to borough watch committees responsible for organising and managing local policing.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.