Posted by Krista J. Kesselring, 6 January 2026.

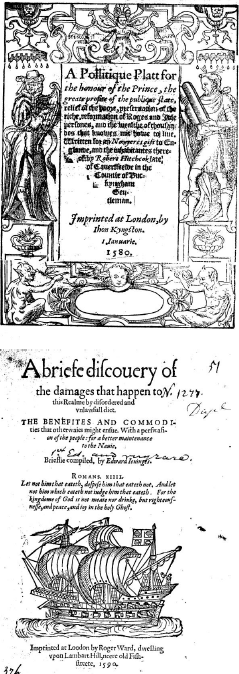

January now sees many people choose to change what they eat, some in hopes that doing so serves a greater good beyond just improving their personal health. Some go vegan: in ‘Veganuary,’ millions of people pledge themselves to a month-long diet of plants rather than animals for their own well-being and that of the planet. In addition to those who abstain from meat out of concerns for animal welfare, some people continue the switch all year long—or at least for a day or two each week, e.g., for ‘Meatless (or Meat-free) Mondays’—to reduce their carbon footprint. In early modern England, some people advocated restrictions on meat-eating for the greater good, too: but they urged the consumption of fish instead of ‘flesh’ and had different collective benefits in mind. As Robert Hitchcock argued in a 1580 publication offered as a ‘New Year’s Gift’ to his readers, turning more often from flesh to fish would promote ‘the great profit of the public state’.[1] Somewhat surprisingly, for more than a hundred years, the laws of Protestant England endorsed ‘fish days’ as policy.

Reasons advanced for a diet of fish over flesh ranged from the spiritual to the ‘politique’.[2] Long centuries of Catholic teaching had urged Christians to abstain from the flesh of warm-blooded animals but allowed them to eat fish—cold-blooded and thus less likely to arouse the carnal appetites—on Fridays, in Lent, and on other days of the year deemed to warrant the penance, discipline, and devotion that fasting embodied. Friday fish days recalled Christ’s sacrifice on the cross; the Lenten fast echoed his forty days in the desert in preparation for his ministry, just before he began recruiting his first disciples from among the fishermen of Galilee. Ignoring the Church’s fasting rules might require a more onerous penance. Early Protestant reformers, in contrast, criticized Catholic fasting as ‘works-righteousness’, an idolatrous belief that one’s own actions could earn salvation. But in England, it was only under the Protestant regimes that emerged from the sixteenth-century reformation that consuming fish in lieu of flesh on select days came to be required by the Crown. A series of post-Reformation parliamentary statutes and royal proclamations restored and even extended the fish days of yore, mandating fines and imprisonment for fast-breaking as a criminal trespass rather than a sin. The statutes and proclamations studiously disavowed any ‘superstitious’ significance for such abstinence: instead, they insisted that eating fish instead of flesh on specified days would serve the interests of the commonwealth or public at large, by better sustaining livestock and seafarers.

A statute passed early in the reign of Edward VI inaugurated a new ‘political Lent’ intended for the benefit of the commonwealth. In an Act that went into effect on May Day, 1549, the drafters insisted that now, living in the clearer light of the gospel, they knew that no day and no kind of meat was more holy than another, but still, godly abstinence was a route to virtue and to ‘subdue men’s bodies to their soul and spirit’. Above all, though, by eating fish, ‘much flesh shall be saved and increased’ and people who lived by fishing would be better set to work. As such, the old fish days would now be required by law, under penalty of a 10-shilling fine and 10 days’ imprisonment for a first offense, doubling for a second. As with religious fasting, some people could secure exemptions, partly given prevailing notions that cold-blooded fish was less nourishing than the meat of warm-blooded animals: the very old, the ill and infirm, people in prison or serving in the military, and women either pregnant or recently delivered who had ‘great lust’ for animal flesh could obtain licenses to set aside fish days. Otherwise, the statute authorized justices of the peace and assize judges to punish violations of the fish day orders, as they would with any other trespass against the king’s peace.[3]

The rationales offered for fish consumption expanded under Queen Elizabeth, as did the number of fish days themselves—and the penalties for failure to comply. Elizabeth’s chief councillor, William Cecil, was determined to strengthen England’s navy in the face of existential threats from abroad. One way to do so was to strengthen the fisheries, which would increase shipbuilding, support coastal communities, and multiply the numbers of men with seafaring experience who might be pressed into service in times of need. And one way to strengthen the fisheries was to require people to eat more fish—sea-fish, specifically. As part of the ambitiously wide-ranging programme of legislation enacted in 1563, Cecil pushed through Parliament ‘An Act touching certain politique constitutions made for the maintenance of the navy’. The Act repeated the earlier claim that fish days helped in ‘sparing and increase’ of livestock but focused on naval needs. To support the domestic fisheries, it included clauses that restricted imports and allowed fishermen to export fish without customs duties. More contentiously, it also mandated that Wednesdays become fish days. As before, some people could acquire licenses for exemptions, now requiring payments graduated by status, but such licenses would not permit the eating of beef on any fish day or veal on those that fell between the autumn harvest and May Day. The Act also heightened the penalties for people who ignored the newly multiplied fish days to a £3 fine and three months’ close imprisonment and added 40-shilling fines for householders who failed to enforce the rules in their own homes. Fines were to be split three ways: one part to the queen’s use, another to the local parish, and a third to the informers who brought cases forward.[4]

Fasting still had spiritual significance, of course, and could be linked to public interests in a variety of ways. Authorities ordered nation-wide public fasts in response to crises such as outbreaks of plague or Catholic plotting, in 1563, 1593, and 1603, and special fast days became even more common during the troubles that preceded the civil wars of the 1640s.[5] But in the 1563 Act that ordered more fish days, a proviso warned people not to misconstrue the measure, which was meant ‘politikely for the increase of fishermen and mariners and repairing of port towns and navigation, and not for any superstition’. To say otherwise was ‘false news’.[6]

Whatever the motives and messaging, enforcement remained difficult. In addition to religious sensitivities about a practice that seemed rooted in Catholicism, some people just didn’t like fish or couldn’t afford it. With fresh sea fish in short supply away from the coasts, many people had to rely on dried, smoked, or salted varieties that they might find less appealing or more costly than cheap cuts of meat. The very fact of requiring fish consumption might not have helped, either, but some contemporaries wanted more stringent and wide-ranging punishments. The London Company of Fishmongers petitioned Parliament to complain of failures to heed the Lenten proclamations and urged that a ‘most plain and very penal law’ be enacted to restrain the butchers who abused their license to sell to people with exemptions by covertly supplying others, too. The fishmongers described a shadowy underworld of meat-selling in ‘divers secret places in the city’ and by vendors from the countryside who snuck in to sell door-to-door on the sly. Butchering animals in the spring breeding season would work against ‘the increase of cattle’, they reminded their audience. Failure to moderate meat-eating, they insisted, caused ‘intolerable damage to the whole commonwealth’.[7] Mariners at Trinity House, Deptford, also urged heavier penalties for non-compliance with fish day orders, thinking something more was needed ‘to terrify, bridle, and restrain’ people, and suggested that fines be used to maintain ports and seafaring infrastructure.[8] On the other hand, some proponents of fish days marshalled evidence that they were working and should thus be retained: one group reported the increased number of ships in coastal towns since the advent of Wednesday fish days.[9]

But heightened enforcement may well have hastened the repeal of ‘Cecil’s Fast’, the new Wednesday fish day. Maurice Beresford’s tallies of cases brought to the Court of Exchequer by informers who hoped to profit from economic legislation suggest that 48% of the suits related to fish days—173 of the 364 in his sample—were filed in 1585, the same year that saw Parliament revoke the Wednesday innovation.[10] As a sop to fishing and marine interests, the repeal Act heightened penalties on innkeepers and others who sold flesh to anyone without an exemption on all the fish days that remained.[11] Competing interests within the fishing sector complicated any straightforward policy—the Yarmouth town council, reliant on the domestic herring fishery, and the London Company of Fishmongers, wanting cheaper imports, sometimes lobbied to different ends, for example.[12] Lenten proclamations were reissued as late as the 1660s and people continued to pay for exemptions, which suggests that some type of enforcement persisted, but apparently never quite to the degree that fishing and marine interests wanted to see.[13]

Meanwhile, men such as Robert Hitchcock with his ‘New Year’s Gift’ continued to advocate a variety of ways to support the fisheries and offered new arguments to make their case. In a proposal for bold shipbuilding plans to counter the Dutch—who fished in sight of English shores in their advanced ‘busses’, effectively seaborne-factories for catching and salting herring—Hitchcock appealed to national honour and argued that more and bigger boats would allow the idle but able-bodied poor to be put to work.[14] In 1590, Edward Jennings urged the restoration of Wednesday fish days and the rigorous observance of those that remained. In an evocative metaphor, he railed against the ‘unlawful diet’ of those who gnawed on the legs of the body politic. Eating flesh instead of fish weakened the navy, put people out of work, and made it more difficult for the poor to get the sustenance they needed: every additional day of abstaining from flesh would save thousands of beasts and help moderate the price of meat. If sufficient laws could not be enacted or enforced, though, he pleaded with people to recognize that what they ate could harm or help the commonwealth writ large.[15]

***

Efforts to tailor diets to a greater good clearly have a history, then, but are propelled by a different impetus now. Using criminal sanctions and informers to police what we eat is something that very few people today would support, for a host of good reasons, and would likely be even less effective than it was in early modern England. But beyond simply making different individual choices, collectively re-examining existing subsidies and regulatory regimes and creating new incentives that reflect longer term valuations of natural resources could promote more sustainable farming—and fishing. While eating fish rather than flesh might be somewhat better even now—for planetary health rather than for the objectives that animated sixteenth-century legislators—modern industrial overfishing means that it comes with its own rising environmental costs. Rashid Sumaila, a prominent fisheries economist, warns that in turning to the sea for sustenance we cannot take ‘everything, everywhere, all at once’: he suggests adopting ‘intergeneration discount rates’ and joins a rising chorus calling for more marine protected areas to serve as ‘fish banks’ for the future.[16] In some ways, calls to set aside zones that will allow fish stocks to regenerate echo earlier calls to set aside days and seasons for the ‘sparing and increase’ of livestock. But we can certainly hope that the new high seas treaty for sustainable use of marine biodiversity that goes into effect this very month is a ‘new year’s gift’ of a more promising sort than what Hitchcock offered his Elizabethan audience.

And with that, best wishes for a happy and healthy new year to all!

Images:

Cover image and final image: detail from Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Fight Between Carnival and Lent (1559), via Wikimedia Commons.

Detail from Pieter Pourbus, The Miraculous Drought of Fishes, part of the triptych of the Fishermen of Bruges (1576), © Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels /photo by author.

Women salting and smoking herring, from Olaus Magnus, Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus (1555).

Notes:

[1] Robert Hitchcock, A Pollitique Platt for the Honour of the Prince, the Great Profite of the Publique State, Relief of the Poore, Preservation of the Riche, Reformation of Roges and Idle Persones, and the Wealthe of Thousands That Know Not How to Live. Written for an Newyeres Gift to Englande, and the Inhabitantes Thereof (London, 1580). On the trope of the literary ‘new-year’s-gift’, see the earlier post on this blog, ‘A New Year’s Gift and the Power to Pardon’.

[2] The account that follows is indebted to R.C.L. Sgroi, ‘Piscatorial Politics Revisited: The Language of Economic Debate and the Evolution of Fishing Policy in Elizabethan England’, Albion 35.1 (2003), 1-24, which expands upon G.R. Elton, ‘Piscatorial Politics in the Early Parliaments of Elizabeth I’, in N. McKendrick and R.B. Outhwaite, eds., Business Life and Public Policy: Essays in Honour of D.C. Coleman (Cambridge University Press, 1986), 1-20. On fasting, see Alec Ryrie, ‘The Fall and Rise of Fasting in the British Reformations’, in Natalie Mears and Alec Ryrie, eds., Worship and the Parish Church in Early Modern Britain (Ashgate, 2013), 80-107 and Chris R. Kyle, “’A Dog, a Butcher, and a Puritan”: The Politics of Lent in Early Modern England’, in Chris R. Kyle and Jason Peacey, eds., Connecting Centre and Locality: Political Communication in Early Modern England (Manchester University Press, 2020), 22-43. For medieval teaching on the virtue of abstinence and why fish was better than flesh in bridling concupiscence, see The Summa Theologiæ of St. Thomas Aquinas. The English Protestant theology of fasting is set out in ‘An Homily of Good Works, and First of Fasting—Parts 1, 2’, in Certain Sermons or Homilies appointed to be read in Churches in the Time of the Late Queen Elizabeth (London, 1852), 254-70. See also Brian M. Fagan, Fish on Friday: Feasting, Fasting and the Discovery of the New World (Basic Books, 2006).

[3] 2&3 Edward VI, c. 19 (1548), An Act for Abstinence from Flesh. The secular reframing of Lent (or at least its laicization) had started about a decade earlier, when Henry VIII responded to the scarcity and high price of fish by proclaiming a loosening of Lenten restrictions that allowed the consumption of ‘white meats’, i.e., eggs and dairy. Tudor Royal Proclamations, ed. Paul Hughes and Francis Larkin (3 vols., Yale University Press, 1964-69), I, pp. 260-1.

[4] 5 Elizabeth I, c. 5 (1563). An Act Touching Certain Politique Constitutions Made for the Maintenance of the Navy. Documents in the State Papers demonstrate Cecil’s guiding hand behind the measure, e.g., The National Archives [TNA], SP 12/27, ff. 280-96; SP 12/28, ff. 43 and 53; and SP 12/31, f. 75.

[5] See especially Natalie Mears, ‘The Culture of Fasting in Early Stuart Parliaments’, Parliamentary History 39.3 (2020), 423-41.

[6] 5 Elizabeth I, c. 5.

[7] TNA, SP 12/77, f. 174.

[8] TNA, SP 12/147, f. 143.

[9] TNA, SP 12/107, f. 170.

[10] M.W. Beresford, ‘The Common Informer, the Penal Statutes and Economic Regulation’, Economic History Review 10 (1957), 221-38 at 226, 228, cited in Sgroi, ‘Piscatorial Politics’, 11. ‘May well have’ as one would need to check the filing dates on these informations to see if they preceded or followed the repeal Act to say with confidence whether the surge in enforcement was a cause or consequence of the legislation.

[11] For the repeal: 27 Elizabeth I, c. 11 (1585), An Act for Reviving, Continuance, Explanation, and Perfecting of Divers Statutes.

[12] On competing interests in the fisheries, in addition to Elton and Kyle, cited above, see Robert Tittler, ‘The English Fishing Industry in the Sixteenth Century: The Case of Great Yarmouth’, Albion 9 (1977), 40-60, and David Dean, ‘Parliament, Privy Council, and Local Politics in Elizabethan England: The Yarmouth-Lowestoft Fishing Dispute’, Albion 22 (1990), 39-64.

[13] For examples of licenses for exemptions, see Charles Partridge, ‘Licenses to Eat Flesh in Lent, 1614-1636’, Notes and Queries 193.6 (1948), 117.

[14] Hitchcock, A Pollitique Platt.

[15] Edward Jennings, A Briefe Discovery of the Damages that Happen to this Realm by Disordered and Unlawfull Diet…with a perswasion of the people: for a better maintenance of the navie (London, 1590).

[16] See, e.g., Ussif Rashid Sumaila, Infinity Fish: Economics and the Future of Fish and Fisheries (Academic Press, 2022), or the summary on his website.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I have come across dietary investigations of neolithic shore-dwellers where there seems little to no evidence of fish in their diet. It continues o puzzle me.

LikeLike