Posted by Sara M. Butler, 5 February 2026.

The church tried its best to vilify social mobility in late medieval England, encouraging good Christians to embrace their place in society (no matter how low!) as ordained by God, and not strive for more. Nonetheless, England’s nascent middle class fantasized of something better. They hoped that their hard work, political hobnobbing, and strategic matrimony would eventually pay off, that they would found a gentry lineage and it would last for generations to come.

For the Frowyk family of South Mimms, that dream became a reality. In the year 1235/36, the thriving family of London merchants purchased the manor of Old Fold, which comprised roughly 132 ½ acres of land in Middlesex (today Hertfordshire). That estate remained in the family’s possession until 1527, nearly three centuries later.[1] Today, there are still traces of the Frowyk family’s past marking the region, with two Frowyk tombstones in the graveyard at St Giles church and a crescent bearing the family name.[2] And yet, for a brief time in the early fourteenth century, those ambitions were thrust into jeopardy. The family’s fate rested in the hands of Agnes, widow of Reginald de Frowyk, whose single-minded determination prevented the family from falling into ruin.

Who was Agnes Frowyk?

Very little is known about Agnes before her widowhood. When was she born? What was her maiden name? Did she come from a family of prominence? When did she marry? Unfortunately, we cannot answer any of these questions. Of course, we know more about her husband and his family. Reginald was the son of Isabella de Durham and Henry de Frowyk I (d.1286), associated with the pepperer guild but a goldsmith by trade.[3] In London circles, Henry was a household name. He was appointed warden of London in 1271 by the king’s council when the citizens could not agree on a mayoral candidate; sheriff in 1274/75, and then alderman of Cripplegate ward as early as 1276.[4] Reginald, his father’s heir, was also a goldsmith. He, too, was a citizen of London and active, though not distinguished, in political circles before his death in 1300 at roughly forty years of age. At that time, he was married to Agnes, and they had one living child, Henry II, aged five.

Thankfully, Reginald was not a tenant-in-chief (that is, he did not hold land directly from the crown through military tenure). If he had, his son would have been removed from his mother’s custody immediately and his guardianship auctioned off by his feudal lord to the highest bidder. As R.H. Helmholz has noted, wardship in military tenure was treated like “a lucrative right rather than as a trust for the child’s benefit.”[5] Instead, Reginald held his land in socage (that is, by agricultural service with a fixed money rent and no expectation of military service). This meant that Agnes was able to assume the role of prochein ami (or, “next friend”) for her son. The forerunner of the modern “guardian ad litem,” a prochein ami was an orphan’s next of kin, usually a male family member who was not entitled to the heir’s land, although when the heir’s mother was still alive it was not unusual for her to take on this responsibility herself.[6] In this position, she was answerable for both Henry’s welfare and his lands: to underscore just how different this guardianship was from military tenure, all profits from those lands were to benefit Henry and the Frowyk family, not Agnes.

The full weight of this obligation surely was driven home in the oath Agnes took before the full husting of the city of London on 15 Nov. 1300, in which she swore to

properly maintain and instruct the said Henry, and would not let him be disparaged or marry without the consent of the Mayor and Aldermen and of his parents [that is, relatives] on his father’s side, and would render true account of his property on his coming of age.[7]

Many other widows in Agnes’s position would have remarried, if only for the help in running the estate. Administering her husband’s properties in Middlesex, Gloucestershire and Hertfordshire, dealing with her husband’s debts, raising and protecting his heir and lands—all of this kept Agnes busy. In an undated petition to the king, she sought to be repaid for a debt owed to her husband for goods purchased for the king’s use.[8] In March of 1305/06, she appeared before the mayor and aldermen of London to acknowledge that she was bound in the sum of 47s. to the commonalty for taxes that Reginald had received from the collectors of the Ward of Bredstrete.[9] In March of 1310, fourteen deeds and writings of diverse purchases made by her father-in-law, Henry de Frowyk I, were delivered to Agnes to hold in keeping for her son.[10]

The Kidnapping of Henry de Frowyk II

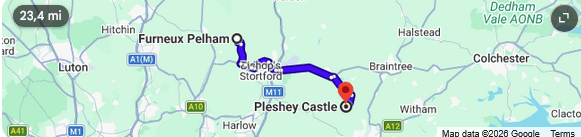

All went seemingly according to plan until Henry reached the age of thirteen years old. It was Saturday, 3 July 1308, and Henry was in Agnes’s custody at one of their homes in Furneux Pelham (roughly 30 miles from South Mimms), when Thomas de Lewkenor, William de Pounz, his son Richard, and John of Felsted, parson of Hadley, arrived with force and arms and abducted (rapuerunt) the young heir. From Furneux Pelham, they conveyed him to Pleshey Castle in northwest Essex, some 23 miles away. The castle was in the possession of Humphrey de Bohun, fourth earl of Hereford, although it is not clear whether the earl was in on the conspiracy to kidnap Henry Frowyk. They kept Henry there by force until 7 Oct. 1308, during which time they coerced him into exchanging vows of marriage with Margaret Pounz, William’s daughter.

Presumably, this marriage was the reason for the abduction. We know that William de Pounz was already an up-and-coming yeoman, having been appointed to assess and collect taxes on behalf of the king for the county of Middlesex in Dec 1306 and against in Nov 1307.[11] For William, Henry’s inheritance valued at £80 per annum would have been a substantial boon. But the Pounz family was simply not in the same league as the Frowyks. Agnes would not have willingly agreed to a marriage between his daughter and her son.

Thomas de Lewkenor was the ace up William’s sleeve. The Lewkenor family had been the lords of South Mimms since 1235/36. The Frowyks were their prosperous neighbors and tenants. It is not hard to imagine that Thomas saw abducting the young (and therefore impressionable) Henry and forcing him into marriage with the daughter of his most trusted officer as an opportunity to gain control of a rival.

What could a single mother in England in 1308 do if her son was kidnapped and forced into marriage? Apparently, she could petition Parliament for assistance. The National Archives date the petition to 1308/9—but because of the nature of the request it was presumably after Agnes had already retrieved her son. She told the MPs, as Henry’s plus procheyne, she was both his guardian and nurse (avoit la garde et la noreture). Because Thomas et al.’s actions had been committed by force, contrary to her and Henry’s wishes, and in breach of the king’s peace, they owed her damages. Parliament’s response was that she should go to chancery and have a writ sued out for the cause.[12] At her subsequent appearance in King’s Bench in January 1310, she finally attached a price tag to what she believed she was owed for her son’s disparaging marriage: £200, an astronomical sum in the year 1308.

The Case in King’s Bench

The case itself is a master class in argumentation. It survives in both the plea roll and as an exemplar in the Year Books—although the pleading, as it is reported, differs tremendously between the two sources.[13]

First, the plea roll: before the justices, Agnes presented the facts of the case. She was in peaceful seisin of Reginald’s son and heir when the defendants abducted Henry, brought him to Pleshey Castle where they forced him into marriage with Margaret Pounz, all to Agnes’ damage of £200. She then proceeded to lay out what was at stake.

As custodian, she was responsible not only for Henry, but also his lands and tenements, which include:

- one messuage [that is, a dwelling house, its outbuildings, and land] and two carucates [a carucate being the amount of land eight oxen could cultivate in a year] of land, 100 acres of woodland, and 20 acres of meadow with appurtenances in South Mimms held in socage from Thomas de Lewkenor by fealty and by service of 5s. and 3d. per annum

- one carucate of land with appurtenances from the counties of Gloucester and Hertford, by service of one pair of golden spurs, or 6d. per annum

- one windmill in Hertfordshire, by service of 1d. per annum

With this inventory, Agnes made it clear why Henry as ward might have been considered a hot commodity.

Then the objections came pouring in.

The defendants denied everything and all injury. Thomas de Lewkenor did the talking for the group. He argued that Reginald had not in fact held his lands in socage from Thomas’s father, Roger, but through homage and military service. He provided a full inventory of the lands and their value per annum in scutage, providing a story so convincing that it is hard to imagine it was anything other than the truth. More important still, Thomas reported that Reginald died in his homage.

Thomas’s claim, if legitimate, had serious implications: Reginald’s death would have brought Henry under Roger Lewkenor’s wardship until the age of 21. And as his father’s heir, that made Thomas Henry’s guardian. Obviously, this was a matter for a jury to determine.

The plea rolls do not include any other objections. The scribe may have simply failed to record them. The Year Book account, however, includes a lengthy list that demonstrates just how determined Thomas’s team of pleaders were to quash this case before it received a proper hearing.

Objection #1: The writ of ravishment of ward exists as a remedy for those who hold in knight’s service. Thus, the writ that Agnes brought before the court is essentially a new writ, and the Provisions of Oxford (1258) make it clear that there will be no new writs. Litigants need to fit their cases within existing writs, rather than having a writ tailor-made to their complaint.

Response: Fortunately, the Statute of Westminster II (1285) acts as a corrective to the 1258 legislation, introducing some flexibility by permitting the creation of new writs, providing they are in consimili casu (that is, for similar situations). Thus, Agnes’s writ is not new and the court must accept it.

Objection #2: Once again, Lewkenor’s team of pleaders struck out against the validity of the writ. The writ of ravishment exists only “for those to whom profit [of a wardship] belonged.” But Agnes could not profit from the wardship; therefore, she should not be able to use the writ.

Response: Once again, her team leaned on the Statute of Westminster II. Chapter 24 states “let not the complainants leave the Chancery without remedy.” Well, this debate was taking place in Chancery (at Westminster, that is). If they allowed Agnes to leave without remedy, they were violating the law.

Objection #3: Thomas’s lawyers then turned to Henry’s age. The age of majority for a ward in socage was 14 years. Fourteen was also the legal age for a male to contract a valid marriage. Agnes claimed Henry was a minor, but in fact he had already had his fourteenth birthday; her custodianship ended that day, thus Henry could not have been abducted. More important still, he was of an age to contract a marriage himself. Indeed, one of Thomas’s lawyers mocked Agnes by claiming that she had mistaken the age of majority for a ward in socage (14) with that of a ward in chivalry (21), and thus once again her writ should be dismissed.

Response: Here, Agnes was resolute: at the time of his abduction, Henry was 13 years of age—still a minor, still in her custody, and too young to contract a valid marriage.

Objection #4: Thomas’s lawyers made one last attempt to discredit the writ. Agnes claimed that the harm was inflicted to her ward, that her ward was forced into a marriage against his will and against hers: why then was she claiming damages for herself? Shouldn’t she be claiming damages on behalf of her heir? Clearly, the poor wording of the writ should invalidate it.

Response: Poor wording, when the intention was clear, was not enough to invalidate the writ.

The Verdict

Despite the best efforts of Thomas’ pleaders, their arguments were unconvincing. It took several court appearances, and three different juries assigned three different tasks to come to a conclusion, but they found in Agnes’ favor.

First, jurors from Hertfordshire declared that the defendants did indeed abduct Henry from Furneux Pelham and carry him by force to Essex. Perhaps most importantly, they clarified that William Pounz was chiefly to blame: everything that was done, was done by his order, command, and instigation (preceptum ordinationem et missionem).

Next, jurors from Essex found that Henry was indeed still a minor when the defendants forced him into marriage against his will and his guardian’s.

Finally, jurors from Middlesex produced a full valuation of Henry’s inheritance (£80) and declared emphatically that Reginald held those lands in socage from Roger de Lewkenor, not through military service.

It is almost unheard of for plaintiffs to receive the actual amount of damages they request: and yet, that is exactly what happened with Agnes. The justices ordered the defendants to pay Agnes £200 in damages, to be given to the heir when he reaches full age in compensation for his marriage to Margaret Pounz. And for the abduction, they were to be imprisoned (although the record did not say for how long).

Not the End of the Story

As it turns out, Agnes’ was not the only lawsuit springing from Henry’s kidnapping. A glance further down in the plea roll reveals that Henry also initiated a suit against Thomas and his accomplices, although his centered entirely on the kidnapping, omitting the marriage entirely.[14] The two suits were initiated a few weeks apart: Agnes first appeared in King’s Bench in the Octave of Hilary (15-22 January 1310), Henry (with his custodian) during the Octave of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary (2-9 February 1310). However, both conclude at roughly the same time: the Octave of St Martin (11-18 Nov 1310).

While the second suit bore Henry’s name, Agnes’ presence, and his youth imply that she may well have been the prime mover—presumably this was a legal strategy intended to maximize damages awarded.

Aspects of Henry’s suit, however, are somewhat unexpected.

First, the list of accused is not the same. Henry’s complaint also targets Thomas de Lewkenor, William de Pounz, and John of Felsted, chaplain; but not William’s son, Richard. In his place are Henry de Gloucester (a London goldsmith and alderman for Lime Street Ward)[15] and, strangely enough, Thomas de Frowyk (Henry’s uncle, also a London goldsmith).

Second, Henry adds new details about the degree of violence involved in his abduction. When his abductors arrived at Furneux Pelham, they were dressed as if for war, sporting acton (a quilted jacket worn under a breastplate), gambeson (a padded defensive jacket) and bascinet (an open-faced helmet). They found Henry in a church (blasphemy, anyone?) from which they dragged him while he was in the midst of raising the hue and cry. He did not know where they brought him (perhaps an attempt to let Humphrey de Bohun off the hook?), but he was maltreated and imprisoned from the moment of the abduction (3 July) until the time of his release on 7 October. Damages for the abduction, ill-treatment, and imprisonment, Henry believed, should be set at £200.

Once again, Thomas rehearsed his tired story: because Reginald held his lands and tenements in military service from Thomas’s father, and he died in homage, there was no crime: Thomas could do what he wanted with his ward. Henry’s jurors were no more convinced than Agnes’. They, too, sided with the plaintiff. While Henry of Gloucester and Thomas de Frowyk were acquitted, the jury convicted the rest: although they, too, ensured to castigate William de Pounz as mastermind. Their punishment: imprisonment, and £100 in damages.

What Happened Next?

Aug 20 1311, after eight months in prison, the king ordered the defendants released on pardon.[16] Apparently they had done their time. Thomas de Lewkenor may even have promised to redeem himself by going on pilgrimage: in June of 1310, he appointed attorneys to tend to his affairs while he went “on pilgrimage beyond seas.”[17]

What we can say is that abducting a minor and forcing him into a marriage was only a small blip on an otherwise stellar career path for both Thomas and William. It did not prevent Thomas from being appointed conservator of the peace for Sussex in 1315/16.[18] And William de Pounz’s son, Richard, became the first keeper and forester of Enfield Chase, suggesting the family remained on an upward trajectory.[19]

Despite Agnes’ contention that Henry was underage and thus his marriage invalid, Henry de Frowyk and Margaret Pounz remained married and seemingly lived happily ever after. They had four children, one of whom (Thomas) stood as knight of the shire in Parliament five times (1351, 1354, 1355, 1357/58, and 1369).[20]

And what about Agnes, our medieval tiger mom, who dropped everything to retrieve her son and protect his person and properties? Like most medieval women, she then disappears altogether from the legal record, leaving us to wonder what happened next.

Endnotes

[1] A.P. Baggs, et al., “South Mimms: Manors,” in A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 5, Hendon, Kingsbury, Great Stanmore, Little Stanmore, Edmonton Enfield, Monken Hadley, South Mimms, Tottenham, ed. T.F.T. Baker, R.B. Pugh (London, 1976), 282-85.

[2] “Tales of the Frowyks,” Churches of St Giles, South Mimms, and St Margaret’s Ridge, (2026),https://stgiles-stmargarets.co.uk/articles-archive/archive-tales-of-the-frowyks (accessed 3 Feb. 2026).

[3] From 1286; Alfred P. Beaven, The Aldermen of the City of London Temp. Henry III – 1912 (London, 1908), 336.

[4] H.T. Riley, ed., Mayors and Sheriffs: Chronicles of the Mayors and Sheriffs of London A.D. 1188 to A.D. 1274 (London, 1863), 157; “List of the Sheriffs of the City of London,” Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_sheriffs_of_the_City_of_London (accessed 3 Feb. 2026); J.J. Baddeley, ed., The Aldermen of Cripplegate Ward from A.D. 1276 to A.D. 1900: Together with Some Account of the Office of Alderman, Alderman’s Deputy and Common Councilman of the City of London (London, 1900), 1.

[5] R.H. Helmholz, “The Roman Law of Guardianship in England, 1300-1600,” Tulane Law Review 52 (1978), 225.

[6] Sue Sheridan Walker, “Widow and Ward: The Feudal Law of Child Custody in Medieval England,” Feminist Studies 3, no. 3/4 (1976), 108.

[7] Reginald R. Sharpe, ed., Calendar of Letter-Books of the City of London: C, 1291-1309 (London, 1901), 81-82.

[8] The National Archives [hereafter, TNA] SC 8/110/5484.

[9] Reginald R. Sharpe, ed., Calendar of Letter-Books of the City of London: B, 1275-1312 (London, 1900), 168.

[10] Reginald R. Sharpe, ed., Calendar of Letter-Books of the City of London: D, 1309-1314 (London, 1902), 223.

[11] Calendar of Patent Rolls [hereafter CPR], Edw. I (1301-1307), 483; CPR, Edw. II (1307-1313), 22.

[12] Rotuli Parliamentorum (London 1767-77), vol. 1, 278, no. 27; also, TNA SC 8/152/7598.

[13] TNA KB 27/ 199, m. 34d; F.W. Maitland, ed., Year Books of Edward II, vol. 2 for Edward II (1308-1310), (Selden Society, vol. 19, 1904), 157-162.

[15] Beaven, The Aldermen, 173.

[16] CPR, Edw. II (1307-1313), 375-99.

[17] CPR, Edw. II (1307-1313), 205-36.

[18] CPR, Edw. II (1313-1317), 402-31.

[19] David Pam, The Story of Enfield Chase (The Enfield Society), 14.

[20] Members of Parliament. Return…, vol. I (1879), 150, 155, 158, 161, and 182.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.