Guest post by Kay Crosby, 19 February 2026.

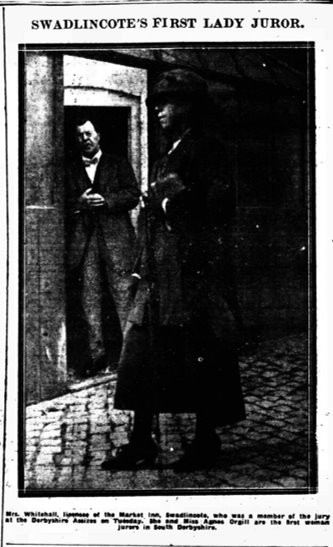

Two photographs make my point. The first is of a Mrs Whitehall, licensee of the Market Inn in Swadlincote, pictured walking to court in 1921. The second is of Rose Henderson, a trans medic, pictured doing the same thing in 2025. In both cases, the image’s subject is walking across the frame, upright and with eyes fixed forwards. Whitehall is walking past a man, leaning casually in the background and freely scrutinising the photo’s principal subject, in contrast to her visible if dignified discomfort. The man is suggestive of a second viewer — us — who is equally free to scrutinise without needing to worry about anybody’s gaze. Likewise, Henderson moves across her picture’s own frame, scrutinised and objectified. Both images portray their subjects as alien women, unwelcome interlopers with no meaningful identity beyond their embodiment of a whole curious group.

Social Processes and State Control

As a feminist legal historian, I am interested in the processes by which these women are reduced to something merely symbolic, and the humanity that both lies beneath and is somehow reconstituted by the conversion of Whitehall into ‘lady juror’ and Henderson into ‘trans medic’. By the 1920s, many women had in fact established themselves as citizens, working for decades in charities and in local government at a time when local work was at least equally constitutive of ‘the citizen’ as was national and imperial work, and where citizenship had not yet become a concept fully captured by law.[1] What was at stake here was less the social reality of women’s citizenship, and more its legal recognition.

For the past decade, I have been writing about what it practically meant that women were permitted to join the UK’s jury system after the passage of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919. What, to coin a phrase, was a woman? As we all understand in 2025, the answer that one gets to this sort of question largely depends on how you staff your administrative agencies. And I have been exploring since about 2015 how those agencies constituted their women jurors during the 1920s and 1930s. First how the number of women on juries was extremely regionally variable;[2] and then how local and national government was using a language of women’s citizenship to positively construct what kind of a woman it was that legal authorities should recognise.[3]

My work has dealt with some pretty low-hanging fruit: let’s count the women on a jury, the women who were summoned and the women who were excused. It has all ended up feeling too numerical, and has largely failed to engage with the human people on my lists. We might compare this to the argument at another recent tribunal concerning the permissibility of trans women changing their clothes or urinating at work. In the Employment Tribunal decision in Kelly v Leonardo, the judge’s argument also briefly collapsed into numbers:

“The claimant submitted that it was disproportionate to sacrifice the dignity and privacy of all female staff (20% of the workforce) to protect the interests of a tiny minority of trans staff (0.5% of the workforce). However only 0.05% of the female workforce had complained or raised a concern about the policy (i.e. the claimant) and it cannot therefore be said that all women considered that their dignity and privacy had been sacrificed.”[4]

It’s a good line, but literally dehumanising. What can we possibly learn at this kind of an analytical distance, beyond adding to the alienating, othering practice of reducing individuals to numerically unusual exemplars? Who actually were any of these people, and what might exploring this question tell us about the legal enforcement of gender inherent in the decision that this particular woman will or will not be who decision-makers have in mind when they use the word?

The Importance of Individual and Group Biography

Early work of mine looked at the electoral registers of a handful of English cities, and found that the women of the jury pool consistently made up only about 5% of the population of people who were, technically, women, but who were overwhelmingly excluded from this new, legally bounded, aspect of women’s citizenship.[5] And if a dozen women were plucked out of that 5% and called upon to serve, well then what was so special about them?

What I’ve been looking at more recently is the personal details of some of these women, to try to understand what it was that qualified them for state recognition as such. Is there anything here that could be developed, to help us understand what sorts of women might be entitled to the state’s recognition as citizens?

Bristol has by far the most complete juror summoning records for the interwar period, so I have started (but do not intend to finish) there. The detail of this city’s records, read alongside the 1921 census and equivalent 1939 records, allows us to build a more sophisticated picture of the women who were being constructed during this period as being worthy of state recognition as citizens.

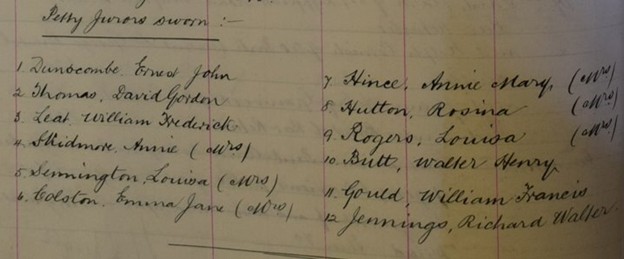

Worthy Citizens? A Sample from the Bristol Quarter Sessions

In the 1921 jurors summoning records at Bristol, 80 women and 333 men were summoned in total. In 1939, 81 women and 469 men were summoned.[6] Having searched for these individuals in the online copy of the 1921 census and the 1939 register (for our purposes the practical equivalent of a census),[7] I have been able to identify 315 of the 413 jurors summoned in 1921, and 409 of the 550 jurors summoned in 1939. While there were more courts than this active in Bristol during the interwar period more generally, the only courts that summoned jurors in these sample years were the quarter sessions (petty trial juries only), and the assizes (common trial juries and special juries).

These women were less likely than their male comparators to live in households wealthy enough to have domestic servants. And for both men and women it was usually the case that a juror was the head of their household. This meant that adult children still living at home were unlikely to serve, and it also meant that male jurors were more likely to live in heterosexual nuclear families compared to their female counterparts. One notable exception here is women at the lower status quarter sessions court, where only 43% were the heads of their households. Feminist campaigners would argue right up until the property qualifications were abolished in the 1970s that these qualifications systematically kept married women off juries;[8] and while this was probably true in general terms, it may have been less true at quarter sessions than it was elsewhere.

These women who were granted recognition as citizens, but who were not the heads of their households, should strictly speaking have been legally impossible. Given that they offer a counter-example to one of the most enduring images of women’s jury service prior to the 1970s, i.e. that a combination of marital status and the property qualifications were a persistent factor in keeping women off the jury, they are worth pausing on for a moment. Who were they, and what can we say about their lives?

All bar the lecturer Jessie Lloyd were simply recorded in the juror book as either a spinster or a married woman. But this brevity obscures much additional detail that can be constructed by cross-refencing details recorded in the census. Five of these women lived in households of women only, living with some combination of mothers, sisters and servants. Thirteen lived with husbands, only two of whom were marginally too old for the statutory age limit on jury service. But everyone except Lloyd, who was a lecturer living at St Matthias’ Diocesan Training College for Female Teachers, lived with family. But Lloyd was far from the only woman in this sample who worked outside of a domestic setting. Indeed, many of those elevated to this kind of formal recognition as citizens ran their own businesses. Kate Burnham ran a ladies’ underwear shop with her sister in Old Market Street; Charlotte Hooper ran a general store on Avon Street; Anne Hardwick ran a drapery shop with her husband on Fishponds Road; Mabel Langdon was an elementary school teacher; Beatrice Pike was a teacher, living above the family dairy shop on Regent Street; and Beatrice Reid ran a tailor’s shop with her husband.

Thirteen of these women had domestic staff, and only eight had neither domestic servants nor a job. They may not have been the heads of households, then, and so their being selected may well have stretched the formal requirements of the new property qualifications (qualifications which officials at Bristol continued to grumble about for some time).[9] But nonetheless these women were predominantly either earning a living or enjoying a comfortable life. And even the remaining eight may have had more to distinguish them than is revealed in the census records. Louisa Senington, for example, had been recorded in the 1921 census as the unemployed wife of a trade union official, when she was in fact Bristol’s second female magistrate and a prominent enough local figure as to eventually receive an obituary in the local press.[10] And so the women who were granted legal recognition as citizens by the local state[11] were often higher status, and often either supported themselves economically or made an independent contribution to civic society. This was the state’s adoption of social citizenship practices.

Census records also allow us to trace these jurors’ ages, in ways that would otherwise only be accessible to us incidentally, by noting who was excused due to old age. The Juries Act 1825 specified that jurors had to be aged between 21 and 60, and so it might reasonably be assumed that the fact only three jurors were excused on this basis in 1921 and four were so excused in 1939 could be taken as evidence of this element of the system working as designed. In fact, the census data for these two years allows us to see not only that this is not true, but also that it is untrue in specifically gendered ways. At all three of the city’s courts in 1921, the summoned women were on average between four and nine years older than the men. The very youngest men, meanwhile, were younger than the statutory minimum age of 21 at two of the three courts; while the youngest women were considerably older, ranging from 33 to 43.

There had been some discussion within the Home Office as late as March 1921 regarding whether the minimum age for women jurors was now 21 (in line with the local government franchise) or 30 (as per the parliamentary franchise). While the Home Office quickly assured itself that the minimum statutory age limit was 21,[12] might it be supposed that the youngest female jurors were so much older than the youngest male jurors owing to a similar misapprehension? I think this is unlikely, for two reasons. First, the Bristol Town Clerk attended a meeting at the Home Office about women jurors in June 1921, where this could have been discussed.[13] Second, as we have already seen, the youngest women were far from the 30 years old that this misapprehension could have led to. And in addition to a prejudice against younger women serving, the prejudice also appears to have extended to older women. A significant number of both women and men were summoned in 1921 despite being over sixty, with this statutory upper age limit seemingly operating more as a grounds for a juror to seek exemption, rather than as forming a blanket exclusion. And the oldest men (72, 86) were six years older than the oldest women (66, 80) in two of the three courts.

This age-related disparity was still apparent in 1939, when at two of the three courts the average age of a woman selected to serve was at least five years older than the average man; and at all three courts the oldest woman (70, 71, 64) was at least five years younger than the oldest man (75, 77, 71). It should be borne in mind that the law was changed in September that year to temporarily create an upper age limit of 65;[14] but even then we must still account for the fact that seventeen men and five women older than 65 were summoned throughout the year.

Why, then, was there this prejudice against summoning either younger or older women? Coen has noted a prejudice at this time against younger women in discussions in the Irish press regarding women jurors in particular.[15] And another explanation may be that there was already an institutional understanding of the types of women who could be expected to serve on a jury. The jury of matrons, which was still sitting in over ten per cent of cases involving a woman who was sentenced to death right up until the institution was abolished in the 1930s,[16] drew its members from older women who were presumed to have enough practical knowledge of the world to judge a fellow woman’s pregnancy. And so it may be that, beyond bland sexism, one factor here was an existing institutional understanding of the women who were entitled to serve as jurors — which practically speaking meant women who were entitled to state recognition as citizens — being inherently middle aged.

The Politics of Women’s Jury Service as seen in the Practices of Legal Officials

As much as the image of Mrs Whitehall constructed her as alien and isolated, we can see in the practices of the Bristol courts at least how women’s citizenship in this context wasn’t really a matter of elevating random women to this new status. Rather, women’s citizenship was being translated out of a pre-existing social practice, taken up and converted by legal institutions into something reserved for independent, middle-aged women. Which is suggestive of what a tiny range of ‘women’ were being constructed as worthy of legal recognition as full citizens.

And that construction was of course entirely in the gift of the men in the council offices who summoned jurors, subject to no meaningful legal oversight. This institutional construction was also able to be deployed by these same men in arguing against the legal recognition of women as citizens. Yes, the law had formally recognised them as such, but perhaps the law should be changed. The judges had already succeeded by the end of 1920 in rolling back women’s right to legal recognition as citizens in the ten major cities that had never previously been required to base jury service on landed property.[17] And now local officials complained that women demanded exemptions at a far greater rate than men, and that they lacked the experience of the men in the jury box. Which meant they should no longer be summoned.[18]

The first of these claims can be exposed as straightforwardly untrue by comparing the numbers of women who were summoned to the numbers of women who showed up after the exemptions process had been completed. The second is harder to compile, but in the Bristol data we can see how this narrative was constructed in real time. Any man summoned between 1920 and 1939 had a 44% chance of being summoned again, while only 20% of women reappeared. Only 6% of women who were summoned at all were summoned as many as three times, and only two women were summoned as many as six times. For men, meanwhile, 10% were summoned at least four times, 5% six times (the highest number for any individual woman), and one man was summoned as many as fourteen times before eventually becoming ineligible to serve because he was dead. We can see here how a disqualifying narrative that women should stop being summoned was being positively constructed by the same men who relied on it.

Concluding Thoughts

The translation of women’s citizenship from a social practice into an institutional fact is an important part of the story of how citizenship came to be captured by law. There is much more that can be said about how the ‘women’ of the jury were constructed following the passage of the 1919 Act, and how their presence and existence were interpellated into culture wars around the alien nature of any woman’s appearance in court in an official capacity. But one thing that I personally find difficult to resolve in doing this work is the question with which I began, balancing Whitehall and Henderson as exemplars and as people, relying on the power of numbers for example without thereby dehumanising the individual constituent women; and unpacking the power games that allowed local and national politics to construct a woman out of the 1919 Act, without decentering the agency of those women who showed up, resisted, acted, and judged. It is a very difficult thing, to move beyond our neutral, dehumanising gaze, and to see the people, with their intersecting characteristics and fully human lives, rather than forever constructing them as dehumanised exemplars.

Author bio: Dr Kay Crosby is a Senior Lecturer in Law at Newcastle University, specialising in feminist legal history and the history of legal institutions. She is currently working on several projects concerning women on English juries and histories of legal gender recognition.

Images:

Main image: Original drawing for “Studies in expression. When women are jurors” cartoon by Charles Dana Gibson (1867–1944). First published 23 October 1902 in Life on pp. 350-351. Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 1: “Swadlincote’s First Lady Juror,” The Burton Observer, 25 June 1921, 8. Image © Reach PLC; used by permission. Image created courtesy of The British Library Board.

Figure 2: “Trans medic used female changing room for years,” BBC News (North-East England, Tees), 4 November 2025.

Figure 3: Bristol Quarter Sessions Record Book, 1910-30 (Bristol Archives: JQS/D/61), 157. Author’s photograph; used by permission.

Notes:

[1] See for example Tom Hulme, After the Shock City: Urban Culture and the Making of Modern Citizenship (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2019), 6-10.

[2] Kay Crosby, “Keeping Women off the Jury in 1920s England and Wales”, Legal Studies 37 (2017): 695-717.

[3] Kay Crosby, “Creating the Citizen Juror in Interwar England and Wales,” The Journal of Legal History 44 (2023): 32-59.

[4] BM Kelly v Leonardo UK Ltd Employment Tribunals (Scotland) (2025), Case No: 8001497/2024, [378], per Judge M Sutherland.

[5] Crosby, “Keeping Women off the Jury,” 706-707.

[6] Jury book, court of Quarter Sessions, 1905-1922 (Bristol Archives JQS/J/2); Jury book, court of Quarter Sessions, 1933-1941 (Bristol Archives JQS/J/4).

[7] Consulted via findmypast.com.

[8] Anne Logan, “‘Building a New and Better Order’? Women and Jury Service in England and Wales, c.1920–70,” Women’s History Review 22 (2013): 701-716.

[9] Kay Crosby, “Restricting the Juror Franchise in 1920s England and Wales,” Law and History Review 37 (2019): 163-207 (188-189).

[10] “Death of Mrs Senington: former lady mayoress of Bristol,” Western Daily Press and Bristol Mirror, 28 November 1947, 3.

[11] Especially in the context of citizenship, the state was still regularly conceptualised at this time as something which existed as much as a local as a national entity. See the discussion in Hulme, After the Shock City, 48-55.

[12] Crosby, “Restricting the Juror Franchise,” 205.

[13] Minute dated 30 Jun 1921, 3pm (HO 45/11071/383085/60).

[14] Administration of Justice (Emergency Provisions) Act 1939, s. 7(3).

[15] Mark Coen, “Through a Narrow Window: Women’s Jury Service in Ireland, 1921–1927,” law&history 9 (2022): 34-63 (46).

[16] Kay Crosby, “Abolishing Juries of Matrons,” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 39 (2019): 259-284.

[17] Juries (Emergency) Act 1920.

[18] Crosby, “Creating the Citizen Juror,” 36.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.