By Cassie Watson; posted 17 March 2018.

One of the most exciting and enjoyable aspects of being a historian is having the opportunity to get close to the lives of people who lived in the past, by reading about their thoughts, actions and feelings in their own words.[1] But for historians of crime, this isn’t as easily done as one might think. There are hundreds of thousands of pre-trial witness depositions in archives all over the country, but they were all created by the legal system, for the legal system — usually the prosecution, not the defence. This means that although direct witness testimony was typically recorded in some detail, there was a step between what the witness said and what was actually written down: the writer was not the witness him- or herself, but a legal official such as a coroner, magistrate, or clerk. These officers of the law did not always write exactly what the witness said: sometimes they summarised what they heard, or did not hear it properly. This problem could be addressed when the deposition was read over to the witness, who was often illiterate, before he or she was asked to sign or put their mark to it; and of course this step was crucial, to render the deposition legally binding. But does that ensure that today we can use such documents as exact representations of what a person really said or thought?

Perhaps the most obvious evidence of this mediated process comes from Wales, where although 80% of the population around 1800 spoke only Welsh, 100% of the witness depositions were written in English![2] The person who was doing the writing was obviously translating what he heard (women did sometimes act as translators, in an informal manner), but we now have no way of knowing how much was left out, or changed ever so slightly. What this means in practice is that although witness depositions give us access to people’s real experiences, and some idea of what they thought about a particular event or crime, we don’t have direct access to their thoughts but instead have to approach obliquely via a third party — the writer.

Occasionally, however, the officials who wrote down the evidence took care to show that what they recorded was indeed what the witness had said — usually by using quotation marks, exactly as we would today. Examples of this are surprisingly few and far between, and it is more common to find short phrases than whole paragraphs of testimony. Ironically, perhaps, it tended to be a prisoner’s words that were recorded verbatim: although officials were not required by law to take a felony suspect’s statement until 1848,[3] procedures instituted in 1826 required coroners to take down in writing the evidence of all witnesses at inquests that resulted in a verdict of murder or manslaughter.[4] And so, every now and then, the case files held by the National Archives at Kew reveal a gem.

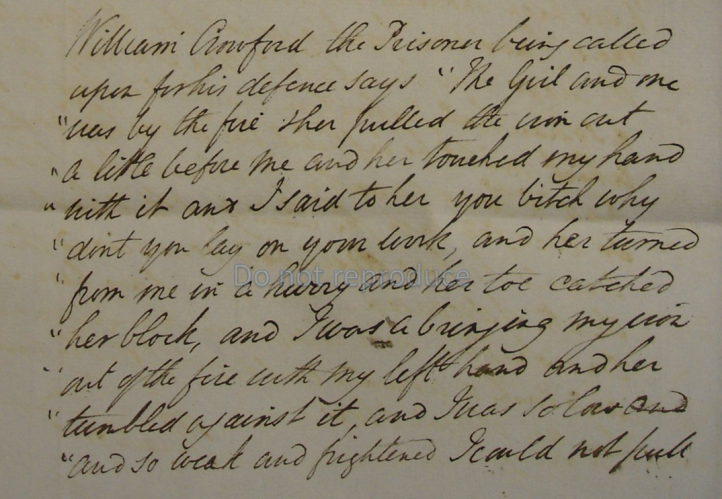

In July 1832 a 14-year-old girl named Eliza Smallwood was killed at a shop in Bromsgrove, Worcestershire, where she was working with her employer, a nail-maker named William Crawford, 34. In what appeared on the surface to be a freak accident that happened when Crawford lashed out at the child, who was both his employee and stepdaughter, the coroner had him arrested, presumably as a precautionary measure. Crawford therefore appeared at the inquest as a prisoner, and when the other evidence had been heard he was given the opportunity to explain his version of events in an account taken down word for word.[5] We know this because of the quotation marks but also because of the authentic regional voice which speaks to us from the past:

“The girl and me was by the fire sher pulled the iron out a little before me and her touched my hand with it and I said to her you bitch why don’t you lay on your work, and her turned from me in a hurry and her toe catched her block, and I was abringing my iron out of the fire with my left hand and her tumbled against it, and I was so low and so weak and frightened I could not pull the iron out but Mrs Emuss pulled it out and that’s all.” The mark X of the prisoner William Crawford

It was common for men and teenage girls to work together closely in nail-making, one on either side of the fire to heat the iron and then head and point the nails.[6] It therefore seems plausible that this event could have been an accident: he seemed distressed when a witness found him crying and praying (loudly). But Crawford gave a slightly odd answer when asked why he’d murdered the girl: he said he didn’t know.[7] The inquest jury thought he was culpable and he was committed for trial on a charge of manslaughter. At the assizes held just three weeks later another of the witnesses, Mrs Elizabeth Emuss (incorrectly reported as Amos), testified that she was in the shop when she heard a scream and then Crawford said “You d—d b—, you have burned my fingers.”[8] When she turned round she saw an iron rod sticking in the victim’s shoulder; she pulled it out, requiring some force to do so. In his defence, Crawford stated that Eliza’s foot slipped and she fell against the iron. Character witnesses spoke favourably on his behalf and according to one, he “used [Eliza] very kindly, barring now and then a blow in the shop”.[9]

It was common for men and teenage girls to work together closely in nail-making, one on either side of the fire to heat the iron and then head and point the nails.[6] It therefore seems plausible that this event could have been an accident: he seemed distressed when a witness found him crying and praying (loudly). But Crawford gave a slightly odd answer when asked why he’d murdered the girl: he said he didn’t know.[7] The inquest jury thought he was culpable and he was committed for trial on a charge of manslaughter. At the assizes held just three weeks later another of the witnesses, Mrs Elizabeth Emuss (incorrectly reported as Amos), testified that she was in the shop when she heard a scream and then Crawford said “You d—d b—, you have burned my fingers.”[8] When she turned round she saw an iron rod sticking in the victim’s shoulder; she pulled it out, requiring some force to do so. In his defence, Crawford stated that Eliza’s foot slipped and she fell against the iron. Character witnesses spoke favourably on his behalf and according to one, he “used [Eliza] very kindly, barring now and then a blow in the shop”.[9]

The newspaper reports, which today offer the most accurate account of nineteenth-century criminal trials held outside London,[10] summarised the evidence but did not attempt to reproduce the words that Crawford used in court or give any indication of what his accent or speech patterns were like. But reading the words that he spoke at the inquest brings him to life nearly two centuries later: ill-educated, petulant, and slightly self-pitying. Did he react to the sudden shock of being burned by stabbing Eliza in the back in a fit of temper, or did she really slip and fall? We shall never know, but the jury thought he was guilty: he was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 18 months in prison. As is sadly common for the victims of most historic crimes, Eliza Smallwood has not left us her words; but nor has she been forgotten.

Images

Trial at a County Court, n.d. Victorian Picture Library, picture number TP146. Downloaded under a commercial use license.

Source: The National Archives, ASSI 6/2, Rex v. William Crawford, Worcestershire, inquest depositions, 6 July 1832. Reproduced by permission.

Girl pointing spike nails. Harold Rylett, “Nails and Chains”, The English Illustrated Magazine 7 (1889-90), 169. Public Domain or Public Domain in the United States, Google-digitized.

References

[1] In Their Own Words: Letters from History (Kew: The National Archives, 2016).

[2] Under the terms of 27 Hen VIII c.26 s.20 use of the Welsh language was forbidden in any legal context and by any office holder.

[3] The Indictable Offences Act, 11 & 12 Vict c.42 required magistrates to take written, signed depositions against individuals charged with an indictable offence, including any answers that the suspect gave to questions put to them. An attached schedule set out the form of wording for the necessary paperwork, stipulating that all statements must be taken down “as nearly as possible” in the exact words of the deponents or accused.

[4] (Peel’s) Criminal Law Act, 7 Geo IV c.64 s.4.

[5] The National Archives, ASSI 6/2, Rex v. William Crawford, Worcestershire, inquest depositions, 6 July 1832. Although his name appears here as Crowford, this was a spelling error. See also Edinburgh Evening Courant, 21 July 1832, 4.

[6] Harold Rylett, “Nails and Chains”, The English Illustrated Magazine 7 (1889-90), 168-169.

[7] TNA ASSI 6/2, inquest depositions, testimony of William Wilson.

[8] Evening Mail, 27 July 1832, 5.

[9] Morning Advertiser, 26 July 1832, 4. In a further example of the difficulty of being certain what people actually heard in court, this report states that Crawford was a sailor.

[10] Judith Rowbotham, Kim Stevenson and Samantha Pegg, Crime News in Modern Britain: Press Reporting and Responsibility, 1820–2010 (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2013). For London, historians can rely on the Proceedings of the Old Bailey 1674–1913, although much of what was said in court was not reported.

[…] published by Legal History Miscellany under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 […]

LikeLike