Posted by Sara M. Butler; 3 May 2018.

In the late fifteenth century, John Medewall brought his petition before the chancellor at Westminster. He explained his dilemma. Purportedly written from his prison cell in London, he recounted how one John Grenefeld had committed to his charge the goods and chattels of Robert Banaster for safekeeping. According to Medewall, this was all above board: he did so with Banaster’s knowledge, and for “the use and behalf” of Banaster. He eventually returned those goods to Banaster, but rather than be rewarded for his good efforts, Banaster sued a plaint of trespass before the sheriffs of London against Medewall, claiming that he had absconded with those very same goods and chattels “with force and arms.” Thereupon, Medewall was arrested and imprisoned until trial. Since that time, through “subtle means,” Banaster had colluded with his brother Thomas, one of the sergeants of London, to embrace a jury so that Medewall would be “condemned unto him in the said action against all right and good conscience.” Despite the availability and popularity of “wager of law,” a process also known as “proof by oath-helper” in which a litigant clears himself of charges by swearing his truth with the support of six (or so) trustworthy citizens, Medewall’s only available option for determination was jury trial because as he states, he

is a man foreign and no free man of the said city so he may not wage his law in the said action by the customs of the said city for to discharge him thereof in that behalf but needs thereof must abide a trial of a jury of the said city with whom your said orator is nothing acquainted nor beknown, to his utter undoing.

Thus, Medewall concludes, without the assistance of the chancellor, specifically a writ of certiorari directed to the sheriffs of London to remove his case for adjudication before the chancel lor, he was doomed to conviction.[1]

lor, he was doomed to conviction.[1]

What stands out most about this case is the fact that John Medewall, bearing a very English-sounding name, describes himself as a foreigner, and as such at a disadvantage in a suit against a London citizen. This predicament is exactly the kind of situation that discourages international trading, and accordingly in 1303 the king had legislated to prevent such injustice, requiring that aliens be permitted to request a mixed jury, composed of half alien migrants, half citizens.[2] If Medewall was in fact an alien immigrant or visitor to London, facing condemnation by a jury of hostile citizens, why didn’t he request the sheriff empanel a jury that included some of his countrymen? The fact that Medewall did not choose this route implies that he was foreign, but not alien.

This predicament was not peculiar to Medewall. Another fifteenth-century petition to the chancellor produces a similar situation. Our plaintiff this time is John Gerard, otherwise known as Gerard Bowyn – an even more English-sounding name – and his case originates in Norwich, pointing to an even smaller likelihood that he was a foreign merchant. Also writing from prison, Gerard explains that Philip Curson of Norwich, a draper, sued a plaint of debt for 28s. against him before the sheriffs of the city, and that he had been imprisoned until trial. Gerard’s version of the story is that one of Curson’s servants, a man named John Beverley, asked Gerard if would be a pledge for goods brought by Henry Taillour, a Dutchman working out of Great Yarmouth (Moche Yermoth). However, Gerard asserts vocally that he did not comply: he refused to stand surety. Nonetheless, when Curson did not receive his goods, Gerard was arrested as surety for the 28s. Gerard surmises that his chances before the court are slim:

Philip Curson is mighty of goods and behavior and stands in great favor of the worshipful and substantial citizens of the same city. And also whereas the same your suppliant should not do nor wage his law against the said Philip Curson in the foresaid plaint in that your beseecher is a foreign and no citizen of the same city and the said Philip Curson is there a citizen and by the usage and custom of the foresaid city a foreign in no plaint shall wage nor do his law against a citizen of the same city but plead to another issue of the country (that is, submit to jury trial). And so your said beseecher by the said custom and usage compelled has pleaded to the issue of a country in the foresaid plaint. Whereas he is neither acquainted in favor nor in knowledge and a country is empaneled by the might and favor of the foresaid Philip Curson by one John Levet, servant to the mayor, and one of the ministers of the same court in partial and favorable manner of jurors maliciously arrayed subveriate(?) and disposed and fully proposed daily saying that if they pass upon the foresaid issue taken between these said parties they shall pass against your said beseecher.

Unwilling to submit himself to a jury poised to convict, Gerard begged the chancellor to intervene by granting a writ of certiorari to the mayor and sheriffs of Norwich, removing the matter to the court of Chancery for adjudication.[3]

Here, we have two very-English sounding petitioners, purportedly on the verge of dramatic conviction, convinced that their “foreignness” puts them at a disadvantage in a suit initiated by a citizen of the city. Neither takes advantage of the provision for mixed juries put in place by the king to guarantee equitable legal treatment of aliens. Are these men actually foreigners?

Thankfully, it is the Oxford English Dictionary to the rescue! The OED reminds us that the medieval English had a peculiar usage for the term “foreigner” to include also “one not a member of any particular guild, a non-freeman.”[4] In the medieval mentality, the city belonged to the citizens alone; its law served to protect them above all. Thus, non-citizens, even if they permanently resided in London (for example) and were English-born, even London-born, were perpetual outsiders, lumped together with Englishmen from outside the city as well as visiting aliens. Indeed, foreigner and “stranger” would seem to belong to the same category of undesirables. This is evident in one of the articles of the king documented at the London Eyre of 1276, which states: “No foreigner nor stranger to keep hostel within the City, but only those who are freemen of the City, or who can produce a good character from the place when they have come, and are ready to find sureties for good behaviour.”[5]

Today, we tend to think that birth alone confers citizenship. Not so in medieval England. Citizenship was claimed by three principal means:

- by patrimony, thus one inherits citizenship from a citizen father;

- by apprenticeship, working for citizenship through an apprenticeship and sponsorship by a guild master; and

- by redemption, that is, by purchase.

The final category was the most readily subject to political manipulation. As Heather Swanson has argued, “entry to the freedom was kept firmly in the hands of the municipal authorities” and the privilege was sold only to “whomsoever they liked.”[6] It is noteworthy that alien-birth was in fact no bar to citizenship (and I realize that forces us to do some mental gymnastics). Barrie Dobson observes that cloth-manufacturers from the Low Countries regularly appeared as citizens in late medieval York’s list of freemen.[7] In most English cities, citizenship was a scarce commodity. At no point in time in London’s medieval history do we find more than 12% of its residents as freemen of the city.[8] In Exeter in 1377, 21% of householders were freemen. Colchester stands out as the exception here: in 1488, over half of the householders of the town were freemen.[9] The one defining feature of freedom, then, was wealth. Thus, as the London historian A.H. Thomas once wryly observed, “residence for a year and a day was held to make a villein into a free man, but not a freeman.”[10] Indeed, servile birth was treated as a bar to citizenship.

Admittedly, the particularity of this terminology is often not recognized. Many historians still regularly translate “foreigner” to mean non-Londoners or aliens.[11] Nor are non-citizens generally deemed worthy of study.[12] This makes me even more curious about what it meant to be unenfranchised? What kind of legal disability did non-citizens – foreigners – encounter?

As our two cases above make clear, wager of law was available only to citizens. Given the  general preference in most cities for wager of law over jury trial, this was a meaningful prohibition.[13] And because only citizens were deemed probi homines (men of probity), jury service in the sheriff’s court was restricted to citizens, putting men like John Medewall and John Gerard at a distinct disadvantage. Procedurally, foreigners were subjected to a more rigorous application of the law. Categorized alongside non-Londoners and aliens, foreigners were seen as a greater flight risk, and accordingly were imprisoned until trial rather than let out on bail as were citizens. In London, when accused of homicide, foreigners had to put themselves on the verdict of forty-two men of the three adjoining wards, rather than a more typical jury of twelve good men and true.[14] The separateness of foreigners and citizens is enshrined in the practice of separate general courts held by the sheriff for each group: two days a week were dedicated to citizens, another two to foreigners (including non-locals and aliens). Until 1268, foreigners in London were denied the right to appoint an attorney specifically on the grounds that if they were allowed to do so, “they would find it easier to pester London citizens with lawsuits than if they had to appear in person.”[15]

general preference in most cities for wager of law over jury trial, this was a meaningful prohibition.[13] And because only citizens were deemed probi homines (men of probity), jury service in the sheriff’s court was restricted to citizens, putting men like John Medewall and John Gerard at a distinct disadvantage. Procedurally, foreigners were subjected to a more rigorous application of the law. Categorized alongside non-Londoners and aliens, foreigners were seen as a greater flight risk, and accordingly were imprisoned until trial rather than let out on bail as were citizens. In London, when accused of homicide, foreigners had to put themselves on the verdict of forty-two men of the three adjoining wards, rather than a more typical jury of twelve good men and true.[14] The separateness of foreigners and citizens is enshrined in the practice of separate general courts held by the sheriff for each group: two days a week were dedicated to citizens, another two to foreigners (including non-locals and aliens). Until 1268, foreigners in London were denied the right to appoint an attorney specifically on the grounds that if they were allowed to do so, “they would find it easier to pester London citizens with lawsuits than if they had to appear in person.”[15]

Citizenship was not compulsory to set up shop or a business; thus, there is no reason to believe that financial success was out of reach of non-citizens. However, municipalities certainly offered their citizens preferential treatment. Restrictions on the ability of non-freemen to trade in markets were “a common feature of late medieval civic ordinances,” Sheila Sweetingburgh tells us.[16] Indeed, London’s oath of citizenship included a promise to report to the chamberlain any foreigns selling merchandise within the city.[17] Being unenfranchised meant being banned from some trades;[18] being forced to sell their wares in less desirable locations at less desirable times, and forbidden from advertising their wares in the normal means (usually by working on the street outside one’s shop);[19] and living in “foreign lanes,” presumably at a distance from the city’s freemen.[20] After the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, foreigners were also given a stricter curfew than London citizens: “no foreigner shall be found wandering in the City by night after six of the clock; or shall go out of his hostel before six of the clock in the morning.”

More important than anything else was the attitude towards the unenfranchised. Citizenship was seen as a “stamp of respectability,” Sylvia Thrupp observes. Citizens were defined as “the better people”: “the more honest, the wiser, the more prudent, and the more discreet.”[21] By analogy, foreigners were everything that citizens were not. This is abundantly apparent in a 1297 order to shut down “The Neue Feyre,” a market in Soper Lane, London, that had been established by “strangers, foreigners, and beggars.” The order explains that abolishment was necessary

by reason of the murders and strifes arising therefrom between persons known and unknown, the gathering together of thieves in the market, and of cutpurses and other misdoers against the peace of our Lord the King.[22]

Clearly, the mental distance between foreigner and thief was a short one.

The inequitable treatment of foreigners did not go unnoticed. Penny Tucker explains that when the king interfered in London law, he did so to “adjust the balance of advantage between citizens and foreigns so that it was less favourable to the former.”[23] However, the king’s chief concern, as the mixed jury infers, was alien merchants, not the non-citizen in general. Thus, no provision was made for a local foreigner to request a mixed jury of half citizens and half non-citizens.

This brings us to a peculiar case. In March of 1365, Nicholas de Upton, a cardmaker, was arrested by the Commonalty of London for having waged his law in the Sheriff’s Court as a foreigner. Whereas, it had since been discovered that he was in fact a freeman of the city by birth. The court ordered Nicholas to pay a fine for contempt of court.[24] Given all of the privilege that was attached to being a citizen, why would any freeman masquerade as a foreigner?

Images

Featured: John Norman (d. 1468), Mayor of London. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

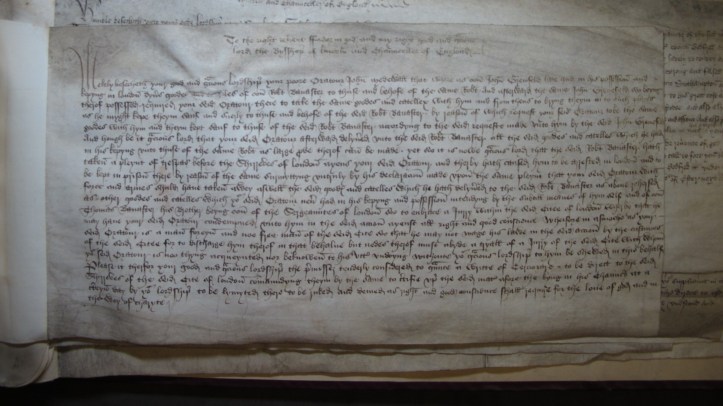

Medewall v. The Sheriffs of London. Via Anglo-American Legal Tradition (University of Houston).

Gerard v. The Mayor of Norwich. Via Anglo-American Legal Tradition (University of Houston).

Norwich Guildhall, seat of local government from early 15th c. to 1938. Via Wikimedia Commons.

[1] The National Archives, Chancery (hereafter TNA, C) 1/64/458, “Medewall v. The Sheriffs of London,” 1475-80, or 1483-85. I have modernized the spelling and included punctuation in order to make the chancery petitions more accessible.

[2] Carta Mercatoria, clause 6 (1303). Susanne Jenks discusses mixed juries of this nature in her, “Justice for Strangers: Experiences of Alien Merchants in Medieval English Common Law Courts,” in The Medieval Merchant: Proceedings of the 2012 Harlaxton Symposium, ed. Caroline M. Barron and Anne F. Sutton (Donington: Shaun Tyas, 2014), 166-82.

[3] TNA C 1/46/448, “Gerard v. The Mayor of Norwich,” 1433-43, or 1467-72.

[4] Oxford English Dictionary¸ headword “foreigner,” def. 2.

[5] The London Eyre of 1276, ed. Martin Weinbaum (London Record Society, vol. 12, 1976), 42-49.

[6] Heather Swanson, “The Illusion of Economic Structure: Craft Guilds in Late Medieval English Towns,” Past & Present 121 (1988), 32.

[7] R.B. Dobson, “Admission to the Freedom of the City of York in the Later Middle Ages,” Economic History Review 26.1 (1973), 14.

[8] Penny Tucker, Law Courts and Lawyers in the City of London, 1300-1550 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 24.

[9] Richard Britnell, “Town Life,” in A Social History of England, 1200-1500, ed. Rosemary Horrox and W. Mark Ormrod (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 63.

[10] Calendar of the Plea and Memoranda Rolls of the City of London: Volume II, 1364-81, ed. A.H. Thomas (London: His Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1929), introduction.

[11] One of the most recent examples is Barbara A. Hanawalt, Ceremony and Civility: Civic Culture in Late Medieval London (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 125.

[12] Surprisingly, Christian D. Liddy, The Politics of Citizenship in English Towns, 1250-1530 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), hardly mentions non-freemen.

[13] Tucker, Law Courts and Lawyers, 193-200.

[14] Chronicles of the Mayors and Sheriffs of London 1188-1274, ed. H.T. Riley (London: Trübner, 1863), 10-11.

[15] Tucker, Law Courts and Lawyers, 290.

[16] Shelia Sweetinburgh, “Kentish Towns: Urban Culture and the Church in the Later Middle Ages,” in Later Medieval Kent, 1220-1540, ed. Sweetingburgh (Kent History Project, vol. 9, 2010), 152.

[17] Hanawalt, Ceremony and Civility, 115.

[18] Ordinance of Glovers, 1349. Memorials of London and London Life in the 13th, 14th and 15th Centuries, ed. H.T. Riley (London: Longmans, Green, 1868), 244-47.

[19] Ordinance of Poulterers, Memorials of London and London Life, 341-47. Sylvia L. Thrupp, The Merchant Class of Medieval London [1300-1500] (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1948), 3.

[20] Articles of Bladesmiths, 1408. Memorials of London and London Life, 567-70.

[21] Thrupp, The Merchant Class, 15-16.

[22] Memorials of London and London Life, 33-36.

[23] Tucker, Law Courts and Lawyers, 34.

[24] Calendar of the Plea and Memoranda Rolls, 1-28.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Hi Sara – enjoyed this piece. You’re right about the lack of writing about this, and there’s some work currently ongoing here in the UK, including a recent London PhD by Charlotte Berry. Also, you might be interested in this: http://www.cambridgescholars.com/between-regulation-and-freedom. Pre-print version available:http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/21654/

LikeLike

Sara

Thanks. Very interesting.

Jon

Jonathan Rose

Professor of Law & Willard H. Pedrick Distinguished Research Scholar Emeritus

Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law

Mail Code 9520

Arizona State University

111 E. Taylor St.

Phoenix, AZ 85004-4467

(480) 965-6513

mailto:Jonathan.Rose@asu.edu

Faculty Profile

SSRN Page

LikeLike

[…] published by Legal History Miscellany, 05.03.2018, under a Creative Commons […]

LikeLike

[…] published by Legal History Miscellany under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 […]

LikeLike