Guest post by Katy Barnett, 18 May 2020.

This blog has recently featured a fascinating post on whether it is possible to steal a peacock. In this post, I’m going to look at the laws surrounding a different kind of bird: the strange historical English laws regarding the monarch and ownership of swans. It is sometimes said that only the Queen may eat swan, and that she owns all the swans in England. This is not strictly correct. The truth, however, is far more interesting.[1]

The Case of Swans

My journey into the law of swan ownership started when I looked at a 1592 case reported by Edward Coke, The Case of Swans, in which he represented Elizabeth I. This case famously confirms the general principles regarding ownership of wild animals, and confirms the rights of the monarch with regard to unmarked swans.[2] It arose when Dame Joan Young and Thomas Saunger were directed by the sheriff of Dorset to round up 400 loose unmarked swans from the rivers of Dorset because the queen, Elizabeth I, sought possession of them. Young and Saunger sought to argue that the swans belonged to them. The right to these swans had previously been held by the local abbot of the Abbey of St Peter at Abbotsbury, an order of Benedictine monks. It might seem extraordinary for monks to have rights to swans, but the description of the monk in the General Prologue to Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales suggests it was not unusual:

Now certainly he was a fair prelaat;

He was nat pale as a forpyned goost.

A fat swan loved he best of any roost.[i]

(Now certainly he was a fair prelate;

He was not pale as a tormented ghost.

A fat swan loved he best of any roast.)

The grandfather of Dame Joan’s first husband had assisted in the dissolution of the monastery, and Henry VIII had allowed him to purchase the estate. The estate had then passed to his grandson and heir (Dame Joan Young’s late first husband, Giles Strangeways, named after his grandfather). Young and Saunger said that they had been given the right to the swans for one year by Strangeways. However, the court held as follows:

It was resolved, That all white swans not marked, which having gained their natural liberty, and are swimming in an open and common river, might be seised to the King’s use by his prerogative, because that Volatilia, (quae sunt ferae naturae) alia sunt regalia, alia communia: [‘because fowl, which are of a wild nature, are sometimes royal and sometimes common’] and so aquatilium, alia sunt regalia, alia communia: [because water birds are sometimes royal and sometimes common’] as a swan is a royal fowl; and all those, the property whereof is not known, do belong to the King by his prerogative: and so whales and sturgeons are Royal fishes, and belong to the King by his prerogative. And there hath been an ancient Officer of the King’s, called Magister deductus cignorum, [‘Master of the Game of Swans’] which continueth to this day.[4]

First, any property right in wild animals was necessarily qualified and limited at common law. However, because swans were ‘royal birds’, the right to these swans could only be granted ratione privilegii (by reason of grant of royal privilege) and could not be transferred to Young or Saunger. Thus, the monarch can claim all unmarked mute swans in English waters.

Interestingly, the land upon which the monastery stood and the Abbotsbury Swannery, both still belong to the descendants of the Strangeways family, and many swans still live there, but the queen no longer claims those swans. This led me to consider: where did Queen Elizabeth I’s ownership of swans come from? The answer is a strange journey through custom and royal prerogative.

The Extraordinary History of the Law of Ownership of Swans

First, the monarch of England only has rights in relation to a particular kind of swan native to Britain, the mute swan (Cygnus olor). Other kinds of swan sometimes seen in Britain such as the whooper swan (Cygnus cygnus) are not covered by the regal privilege.

Secondly, the ancient origins of the monarch’s ownership of swans are shrouded in mystery. The first mention of mute swans being a ‘royal bird’ comes from Gerald of Wales (‘Giraldus Cambrensis’) in the late 12th century.[5] It is generally deemed part of the royal prerogative by custom, then entrenched in case law and statute.

In medieval times, swans were luxury goods. The precise reason for this is unclear but it has been hypothesised that it may relate to their beauty, their solitary nature, and the difficulty in keeping swans:

Since ancient times, swans have been associated with tranquility and nobility, featuring in myths and stories around the world. Their high status is likely to have come about because of their perceived beauty and natural behavior; they are solitary birds, strong and aggressively protective of their young but at the same time graceful and elegant on the water…

Swans were luxury goods in Europe from at least the 12th century onward; the Medieval equivalent of flashing a Rolex or driving a Lamborghini. Owning swans signaled nobility, along with flying a hawk, running hounds or riding a battle-trained destrier. Swans were eaten as a special dish at feasts, served as a centerpiece in their skin and feathers with a lump of blazing incense in the beak. They were particularly associated with Christmas, when they would be served in large numbers at royal feasts; forty swans were ordered for Henry III’s Christmas celebrations in 1247 at Winchester, for example.[6]

As noted earlier the monarch could grant a privilege to own swans to certain favoured people. But this raises the question: how do you show that you own a swan?

How Do You Prove You Own a Swan?

The difficulty with any wild animal is that it is hard to prove ‘ownership’, and as the Case of Swans notes, any ownership is necessarily partial or qualified. In fact, this was recognised in Roman law as well, which was the first ancient legal system to categorically distinguish between wild animals (ferae naturae in Latin) and tame animals (mansuetae naturae in Latin). The Digest of Justinian quotes the Roman jurist Gaius as saying that: “all animals taken on land, sea, or in the air, that is wild beasts, birds, and fish, become the property of those who take them,” but that “when they escape from our control and return to their natural state of freedom, they cease to be ours and are again open to the first taker.”[7] These principles flowed through into the English common law, so that the thirteenth-century jurist and cleric, Henry de Bracton expressed similar principles regarding wild animals.[8] The ownership of bees, for example, causes notorious difficulty because while hived bees can be owned, bees swarm. It is difficult to know to whom a moving swarm belongs, and there is no way of marking bees as ‘yours’. Once they go onto someone else’s land, at common law, you may lose ownership and the bees may gain their freedom if the landowner doesn’t allow you access to them.[9]

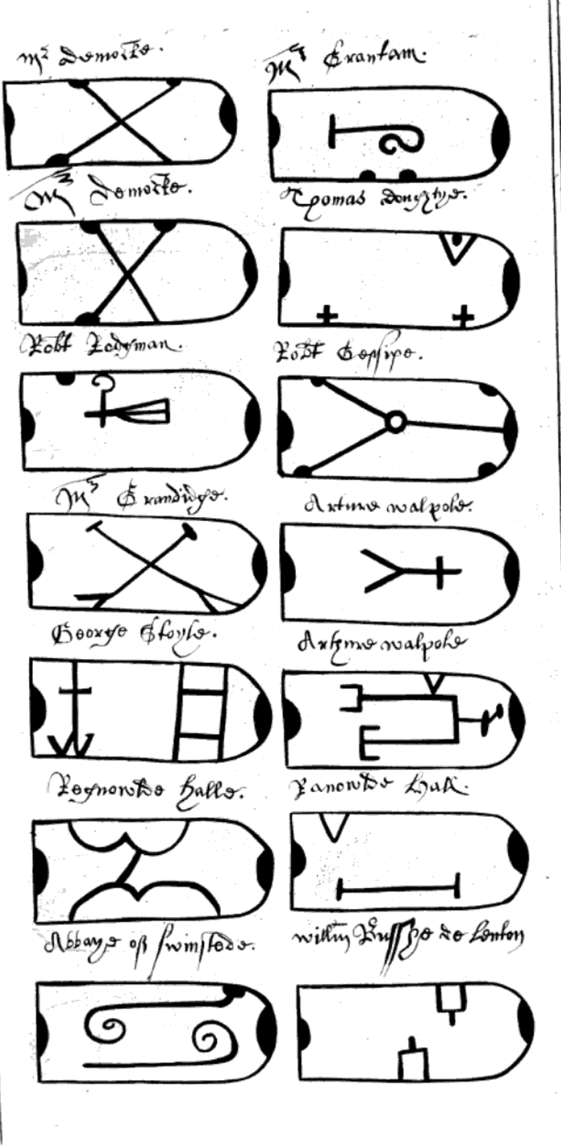

However, with swans, it is possible to mark them, and indeed, in the 13th century, English owners of swans started to place ‘marks’ on wild swans’ beaks (called in Latin cigninota) after the king granted them the right to do so. In 1361, Thomas de Russham was given responsibility by the king for “the supervision and custody of all our swans as well as in the water of the Thames as elsewhere within our Kingdom.” Thereafter, the king had an officer who was Master of the King’s Game of Swans (also known as the Royal Swan-herd, Royal Swannerd, or Royal Swan-master). A declaration in 1405 to 1406 reiterated that only the king had the right to grant swan marks. Until that time, ownership of swans had been governed by customary law.

However, with swans, it is possible to mark them, and indeed, in the 13th century, English owners of swans started to place ‘marks’ on wild swans’ beaks (called in Latin cigninota) after the king granted them the right to do so. In 1361, Thomas de Russham was given responsibility by the king for “the supervision and custody of all our swans as well as in the water of the Thames as elsewhere within our Kingdom.” Thereafter, the king had an officer who was Master of the King’s Game of Swans (also known as the Royal Swan-herd, Royal Swannerd, or Royal Swan-master). A declaration in 1405 to 1406 reiterated that only the king had the right to grant swan marks. Until that time, ownership of swans had been governed by customary law.

In 1482 and 1483, Edward IV’s Act for Swans was passed to prevent unlawful keeping of swans by “Yeomen and Husbandmen, and other persons of little Reputation”. Accordingly, the only people who could have swan marks or own swans were noble and rich people: those who “have Lands and Tenements of Estate of Freehold to the yearly Value of Five Marks above all yearly Charges.” If a person was now disqualified from owning swans, they were to divest themselves of ownership, and if this was not done before Michaelmas, the king’s subjects who qualified for ownership of the swans were entitled “to seise the said Swans as forfeit; whereof the King shall have one Half, and he that [shall seise] the other Half.”[10] This is what is known as a ‘sumptuary law’: a law restraining someone from owning or consuming something based on social class, designed to enforce social hierarchies.

Formal registration of swan marks became a practice around this time. Additional codes and ordinances were enacted as to who should own swans and cygnets in particular areas. As The Case of the Swans notes, only the monarch could claim unmarked mute swans, although the monarch also had several of his or her own marks. The only other group of people who are still allowed to legally hunt and eat unmarked mute swans are the fellows of St John’s College, Cambridge, a privilege granted for royalist support in days gone past: swan traps remain in the walls of the College.[11]

The marking, recording and disposal of swans was known as ‘swan-upping’, and was conducted by the swan-master. People would catch the swans, record the ownership of the birds and their offspring, and place markings upon the beaks of the birds. It seems that the marks were achieved by inscription with a knife or by branding. The swan-master was to meticulously maintain the marks in an ‘upping book’. As The Case of the Swans notes, there was an elaborate system whereby ownership of cygnets belonging to a pair of swans owned by two different people were divided between them: one cygnet went to the owner of the cob, one to the owner of the pen, with the owner of the cob having the first pick. Alternatively, if there was only one cygnet which was disputed, the owner might pay half the value to the loser, or might be promised the next bird from the match. If there were three cygnets, the person upon whose land the nest was built might have an entitlement to it, although the value would be less than the other two, as long as he paid a fee to the Monarch. This is different from the ownership of most baby animals, where, at common law, the offspring belong to the owner of the mother. In The Case of the Swans, Edward Coke explains this as follows:

The marking, recording and disposal of swans was known as ‘swan-upping’, and was conducted by the swan-master. People would catch the swans, record the ownership of the birds and their offspring, and place markings upon the beaks of the birds. It seems that the marks were achieved by inscription with a knife or by branding. The swan-master was to meticulously maintain the marks in an ‘upping book’. As The Case of the Swans notes, there was an elaborate system whereby ownership of cygnets belonging to a pair of swans owned by two different people were divided between them: one cygnet went to the owner of the cob, one to the owner of the pen, with the owner of the cob having the first pick. Alternatively, if there was only one cygnet which was disputed, the owner might pay half the value to the loser, or might be promised the next bird from the match. If there were three cygnets, the person upon whose land the nest was built might have an entitlement to it, although the value would be less than the other two, as long as he paid a fee to the Monarch. This is different from the ownership of most baby animals, where, at common law, the offspring belong to the owner of the mother. In The Case of the Swans, Edward Coke explains this as follows:

And the Law thereof is founded on a reason in nature; for the Cock Swan is an emblem or representation of an affectionate and true Husband to his Wife above all other Fowle; for the Cock Swan holdeth himself to one female only; and for this cause nature hath conferred on him a gift beyond all others; that is, to die so joyfully, that he sings sweetly when he dies; upon which the Poet saith,

Dulcia defecta modulatur carmina lingua, Cantator, cygnus, funeris ipse sui, &c

(The swan, chanter of its own death, modulates sweet songs with failing tongue)[12]

And therefore this case of the Swan doth differ from the case of Kine, or other brute beasts.[13]

The only private ‘individuals’ to now own marked swans are the Dyers Company and the Vintners Company. They still conduct annual swan uppings with the queen on the River Thames, but now for the sake of swan conservation.[14]

Courts of Swan-mote: Special Courts Regarding Swans

The king formed special courts to apply the law of swans, called the Courts of Swan-mote or Swan-moot. These courts settled disputes regarding swan ownership. The Master of the King’s Game of Swans was responsible for enforcing the king’s rights in relation to swans. It later became a profitable office, and regional deputies were appointed. Strict rules promulgated by local swan owners protected the monarch’s swans from being harmed. As an example, the Ordinances made in respect of Swans on the River Witham in Lincoln in 1523 set out the following rules:

…that there shall no fisher, or other man that hath any ground butting on any water, or stream, where swans may breed, or of custom have bred, shall mow, shear, or cut any thackets, reed, or grass, within 40 feet of the swan’s nest, or within 40 feet of the stream, on pain of every such default to forfeit until the king, or his Deputy, xl [40 shillings]…

…that there shall no manner of person or persons, hawk, nor hunt, fish with dogs, or set nets, or snares, or engines, for no fish, or fowl, in the day time, or shoot in hand gun, or cross bow, between the Feast of Philip and James, and the Feast of Lammas, in pain for every such default, to forfeit unto the King or his Deputy, the thing that is set, and in money the sum of 6s. 8d.

…that there shall no hemp or flax be steeped in any running waters, nor within 40 feet of the water, nor any other filthy thing be thrown in the running waters, whereby the waters may be corrupt, nor no man to encroach on the running water, whereby the waters may be hurt, by any kind of means, in pain of every such default, to forfeit unto the King, or his Deputy, xl [40 shillings]…[15]

Stealing swan eggs was forbidden, under pain of imprisonment and fines. During the reign of Henry VII, stealing ‘the eggis of any faucon, gossehauke laners or swannes out of the neste’ was punishable by imprisonment for a year and a day and a fine, half to be paid to the king, and half to be paid to the person on whose land the nest was.[16] During the rule of James I, anyone who took ‘the Egges of any Phesant Partridge or Swannes out of the Neasts, or willinglie breake spoile or destroy the same in the Neaste’ risked punishment of three months’ imprisonment without bail unless they paid a fine of 20 shillings (to be applied for the use of the poor of the parish) for each egg taken or destroyed.[17]

The Swan-master was also responsible for keeping swans safe in inclement weather.

What About the Sturgeon and the Whales?

Eagle-eyed readers will note that the The Case of Swans also observed that the monarch of England owns all whales and sturgeon as ‘Royal Fish’.[18] This was stated in 1322, by an Act of Edward II called Prerogativa Regis or Of the King’s Prerogatives. It provided:

Also the King shall have Wreck of the Sea throughout the Realm, Whales and [great] Sturgeons taken in the Sea or elsewhere within the Realm, except in certain Places privileged by the King.[19]

Porpoises and dolphins are also regarded as falling under this law.

The monarch’s entitlement to the ‘Wreck of the Sea’ was removed in 1894 by the Merchant Shipping Act 1894, but the rest of this particular section remains in force. Consequently, in 2004, when a Welsh fisherman named Robert Davies caught a 10-foot long sturgeon, he offered it to the Receiver of Wrecks, the official presently appointed to dispose of ‘royal fish’ in England, Wales and Northern Ireland on behalf of the queen. The queen declined it and said that Mr Davies was entitled to dispose of it as he wished.[20]

Of course, the fact that whales and other cetaceans are named as ‘royal fish’ raises the inevitable objection that whales, porpoises and dolphins are not in fact fish at all. In his 1935 book Uncommon Law, A.P. Herbert invented a fictional case in which a dead whale washes up on the shore of a town, and all parties (including the monarch) disclaim liability for disposing of it as the whale starts to decompose and smell unpleasant. Eventually, the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food points out that the whale is a mammal, not a fish, and the case is adjourned.[21]

The current Queen, Elizabeth II, does not exercise her rights in relation to unmarked swans other than those in certain stretches of the River Thames,[22] nor does she apparently wish to claim sturgeon.

It remains illegal to eat swans in England, but for different reasons to those in the past. Mute swans are protected as a ‘wild bird’ by the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 (UK), and it remains an offence to kill, injure or take a wild bird, or to take, disturb or destroy the eggs of a wild bird.[23] The only person who could presumably eat swan in England is the queen, but this is simply because she has sovereign immunity, not because of any deeper principle.[24]

As an Australian, I cannot help but be amused that the queen’s prerogative does not extend to the Australian black swan (Cygnus atratus), only to the mute swan (Cygnus olor). Hence, although some small populations of Australian black swans imported to England have flourished there,[25] the queen has no right to them.

Biography: Katy Barnett is a Professor at Melbourne Law School, Australia, specialising in private law. She is currently writing a book on animals and the law (to be published by Black Inc) with her colleague Professor Jeremy Gans, and this post emanated from that research.

Images:

Feature image of a swan taken from British Library, Harley MS 4751, fo. 41v, used by permission of the British Library.

Image of swan marks taken from Ordinances respecting Swans on the River Witham, in the County of Lincoln: together with an Original Roll of Swan Marks, appertaining to the Proprietors on the said Stream, in Archaeologia or Miscellaneous Tracts Relating to Antiquity, Volume 16, page 152 in the public domain here.

Print of ‘Swan Upping on the Thames’, from Henry Robert Robertson’s Life on the Upper Thames, 1875. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

Notes:

[1] See Arthur MacGregor, ‘Swan Rolls and Beak Markings: Husbandry, Exploitation and Regulation of Cygnus olor in England, c. 1100 – 1900’ (1997) 22 Anthropozoologica 29 for a detailed description of the history and traditions behind swan ownership. Sarah Laskow, ‘Why the Queen Owns All the Swans in England’ (14 May 2018) Atlas Obscura also provides a helpful history.

[2] The Case of Swans (1592) 7 Co Rep 15b.

[3] The Riverside Chaucer (Oxford University Press, 1988) 26.

[4] The Case of Swans (1592) 7 Co Rep 15b, 16a–16b.

[5] ‘Swan Upping: History and the Law.’

[6] Emily Cleaver, ‘The Fascinating, Regal History Behind Britain’s Swans’ Smithsonian Magazine (31 July 2017).

[7] Digest of Justinian 41.1.1, 41.3.2.

[8] Henry de Bracton, De Legibus et Conseutudinibus Angliae (‘On the Laws and Customs of England), GE Woodbine (ed), transl SE Thorne, (London: Publications of the Selden Society, 1968–77) l. 2, c. 1, fol. 9 [De Adquirendo Rerum Dominio,vol 2, 42].

[9] Kearry v Pattinson [1939] 1 KB 471.

[10] Act for Swans,22 Edw IV c. 6: The Statutes of the Realm Volume 2 (1377–1504), 474.

[11] http://www.thenakedscientists.com/HTML/content/interviews/interview/957/

[12] This is a reference to Martial, Epigrams, 13.77.1.

[13] The Case of Swans (1592) 7 Co Rep 15b, 17b. In fact, the ‘swan song’ is entirely mythical, but there is a germ of truth to the pair bonding – swans mostly stay together: see Louise Crane, ‘The Truth About Swans’ (4 December 2014).

[14] Liam James ‘The ancient royal tradition of counting swans on the River Thames’ (17 July 2019) The Independent.

[15] Ordinances respecting Swans on the River Witham, in the County of Lincoln: together with an Original Roll of Swan Marks, appertaining to the Proprietors on the said Stream, in Archaeologia or Miscellaneous Tracts Relating to Antiquity, Volume 16, 153. This particular Ordinance was described by Sir Joseph Banks, the naturalist familiar to Australians as the namesake for Banksia flowers and Bankstown.

[16] An Act against taking of Feasaunts & Patridgs (11 Hen VII c 17, 1495) in Statutes of the Realm Vol II, 581.

[17] An Acte for the better execution of the intent and meaninge of former Statutes made againste shootinge in Gunnes, and for the preservation of the Game of Phesantes and Patridges, and against the destroyinge of Hares with Harepipes, and tracinge Hares in the Snowe (1 Jac I c 27, 1603–4) in Statutes of the Realm Vol II, 1055.

[18] The Case of Swans (1592) 7 Co Rep 15b, 16a–16b.

[19] Prerogativa Regis or Of the King’s Prerogative 1322 (15 Edw II cc. 13 – 17 s xiij)

[20] ‘Fisherman lands £8,000 catch’ (2 June 2004) BBC News.

[21] AP Herbert, Uncommon Law (Methuen, 1935) 7–12.

[22] ‘Swan Upping: Introduction’ https://www.royal.uk/swans

[23] Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 (UK), s 1. (Section 2 gives exceptions).

[24] Sarah Laskow, ‘Why the Queen Owns All the Swans in England’ (14 May 2018) Atlas Obscura.

[25] https://web.archive.org/web/20150502223544/http://www.wildlifeextra.com/go/news/black-swan.html#cr

[…] “This blog has recently featured a fascinating post on whether it is possible to steal a peacock. In this post, I’m going to look at the laws surrounding a different kind of bird: the strange historical English laws regarding the monarch and ownership of swans. It is sometimes said that only the Queen may eat swan, and that she owns all the swans in England. This is not strictly correct. The truth, however, is far more interesting …” (more) […]

LikeLike

[…] Katy Barnett, ‘The Ownership of Swans in English History: Does the Queen Own All the Swans?’ on Legal History Miscellany (18 May 2020) https://legalhistorymiscellany.com/2020/05/18/does-the-queen-own-all-the-swans/amp/; […]

LikeLike

[…] https://legalhistorymiscellany.com/2020/05/18/does-the-queen-own-all-the-swans/ […]

LikeLike

[…] The Ownership of Swans in English History: Does the Queen Own all the Swans? […]

LikeLike

[…] and indeed constitutional dimension to the Swan Upping story. As Katy Barnett explains in a most instructive post over at Legal History Miscellany the reason for the glorious scarlet uniforms’ presence is […]

LikeLike

[…] and certainly constitutional dimension to the Swan Upping story. As Katy Barnett explains in a most instructive publish over at Authorized Historical past Miscellany the explanation for the fantastic scarlet uniforms’ […]

LikeLike