By Cassie Watson; posted 30 December 2020.

English legal records include information about the service experiences of thousands of law officers of all ranks, from eighteenth-century excisemen and parish constables to Victorian beat constables and Edwardian detectives. Most appear as witnesses testifying to the steps they took when a crime was discovered. Some were themselves prosecuted as criminals. A much larger number became the victims of violent crime, including serious assault at the hands of angry inebriates or protestors, and murder by poachers or robbers attempting to escape arrest.[1] The academic study of police officer fatalities benefits from the inclusion of such historical data,[2] but individual stories reveal characters who might otherwise be overlooked in studies of interpersonal violence. The murder of PC Timothy Daly at Highbury in May 1842 is a Victorian case in point. He was the fifteenth Metropolitan Police officer killed in the line of duty, the first to be shot, and the only one killed by a highway robber,[3] but he and his killer have been largely overshadowed by the far more famous murder and mutilation committed by Daniel Good a month earlier.[4]

Highway Robber or Footpad?

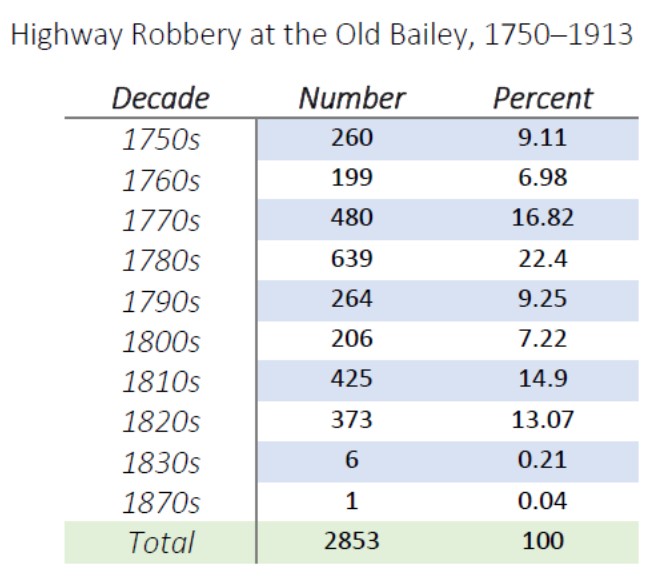

For a start, just how common was highway robbery by the 1840s? The short answer is, not very. Robert Shoemaker has noted that “more people were indicted for highway robbery at the Old Bailey between 1770 and 1800 than in the previous half-century,”[5] but statistics compiled using the online Proceedings of the Old Bailey show its near total disappearance after 1828.[6] Bearing in mind the fact that the streets of London (and other cities and towns) had long been designated as highways,[7] it is obvious that not all of these robbers were necessarily mounted.

Indeed, the man who shot PC Daly was a serial offender who committed his crimes on foot, and although he was described in at least one report as a “footpad,”[8] most press accounts described his offences as “highway robberies” committed by a “highwayman”.[9] There was however none of the mystery and romance that had once been associated with this form of criminality. In reality, Daly’s killer was a canny criminal who ultimately confessed to having committed

“between 20 and 30 highway robberies. He said he managed to escape for a considerable time, by admitting no companion in his crimes, and by uniformly selling the watches and other articles he plundered to the Jews, instead of taking them to the pawnbrokers. He always appeared in a mask, and seldom met with the least resistance from those whom he attacked.”[10]

“Stop that man without a hat, he has shot a policeman.”

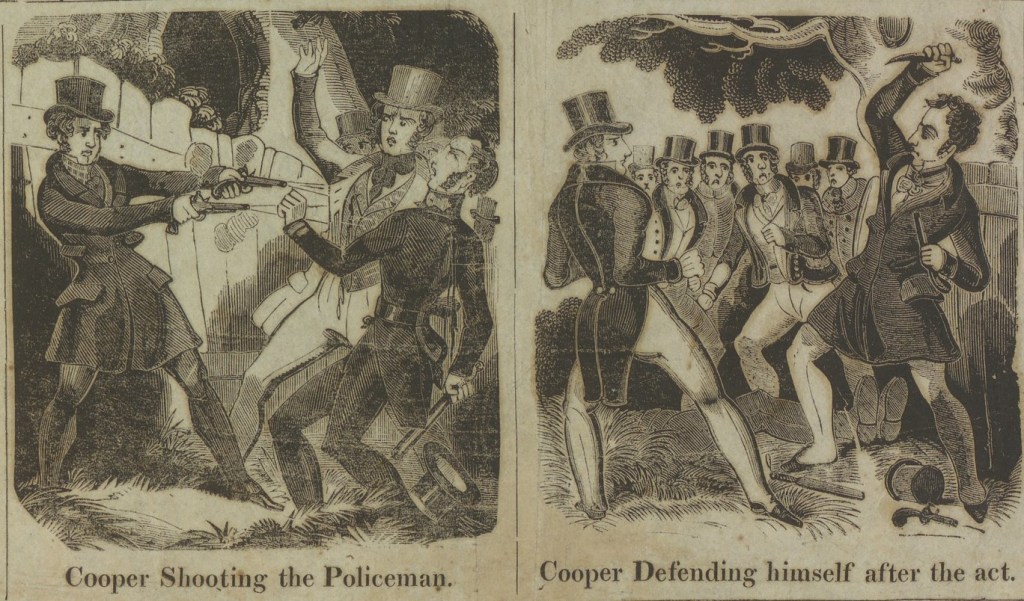

The story began in April 1842 when the police stationed at Islington, N Division, began to receive complaints from people alleging they had been stopped “upon the highway in fields adjacent to Hornsey Wood” and robbed of their cash and possessions by a “dark complexioned young man of spare habit of body” armed with two horse pistols — a fact that almost certainly contributed to his portrayal as a highwayman. At first the police paid little attention to these reports — because they concerned highway robbery? — but when they became too frequent to ignore an officer “noted for his activity and courage” was sent to the area.[11] This was PC Charles Moss, and on the afternoon of 5 May he spotted a man who fitted the description and gave chase.

Seeing that he was pursued, the man — 23-year-old unemployed bricklayer Thomas Cooper from Clerkenwell, took aim and fired, shattering Moss’s left arm, before running off in the direction of Highbury, still followed by Moss. Prompted by the alert of a passer-by, “Stop that man without a hat, he has shot a policeman,”[12] the pursuit was quickly joined by a number of other men, including a journeyman baker named Charles Mott, and PCs Mallett and Daly of N Division. Cooper was soon cornered against a wooden fence but he had had time to reload his pistol: Mott rushed at him but slipped and was shot in the shoulder; and as Daly then moved toward him, Cooper fired the other pistol. The ball, later found in the road, passed through Daly’s chest and out at his side, and he dropped dead on the spot.

Cooper was apprehended and taken to the police station, where an enraged crowd soon gathered, and it was reported that in addition to his two flintlock cavalry pistols, he carried a sharp clasp knife. Although the police searched him, they apparently did not do so thoroughly: by the next morning he had taken poison and was in a very low state, vomiting and faint, yet he was brought before the police court at Clerkenwell on the Friday, Saturday and Monday before being committed to Newgate to await trial.[13] Moss and Mott got better medical care: they were taken to St Bartholomew’s Hospital, where the latter was still an in-patient when Cooper’s trial took place on 18 June.[14] PC Daly’s body was taken to the Highbury-barn Tavern, where an inquest was opened on Friday 6 May.

The Inquest

The inquest was presided over by the redoubtable coroner, surgeon, MP and founder-editor of The Lancet, Thomas Wakley (1795–1862), who was incensed by the fact that the Clerkenwell magistrates held their committal hearing at the same time and had instructed the police to produce Cooper, overriding his order that Cooper should be brought to the inquest. Wakley used the opportunity this provided to rail against magisterial challenges to coronial authority, ostensibly because it was unfair to Cooper who could not be present to hear the evidence against him. But Wakley’s grievance clearly extended beyond Cooper:

“The coroner’s court was by far an older institution and superior court to that of a police magistrate, and the latter had no right to infringe upon and supersede its authority. … He (the coroner) deeply regretted that it would be his duty to speak to the Secretary of State on the matter, for he was subject to no such annoyance in other districts of the metropolis as in that particular district.”[15]

But the inquest had to proceed without the accused man, even though Wakley adjourned it for that purpose: having been committed to Newgate, Cooper could not be produced, an interesting fact in itself. Furthermore, the inquest jurors clearly felt as Wakley did, for they added a rider to their verdict that Daly had been “wilfully murdered by a man calling himself Thomas Cooper,” stating that:

“They cannot but regard what has passed on this occasion as an effort purposely made to destroy the powers and utility of the inquest, and they will be most happy to sign a memorial to the Secretary of State, the better to secure the ends of justice with respect to the jurisdiction of the coroner’s inquest, the only court in the country the presiding officer of which is elected by the people.”[16]

Mad; or just Bad?

As upwards of twenty people had seen Cooper shoot Daly, his defence counsel S. Horry had an uphill battle on his hands, possibly the more so if this was Sidney Calder Horry (1810–1882) who wrote a book on the Law and Practice of Insolvents in the Bankrupt Court in 1844! Horry decided to wage battle on the grounds of criminal irresponsibility, using his cross-examination of the surgeon who carried out the post-mortem, Edward Drewry, as an opportunity to explore Cooper’s alleged insanity. Drewry, though probably no expert on such matters, clearly knew something about the new area of medical practice known as alienism — early psychiatry — and tried to parry Horry’s repeated efforts to get him to agree that Cooper was insane. He was worn down, however, and finally agreed that Cooper’s sleeplessness, excessive appetite, dirty habits, claims that he was Dick Turpin and King Richard, and desire to “dig his father out of his grave, because it was no use he should lie there,” might indicate that he was not in a sound state of mind.[17]

But the judge, Baron Gurney, was growing weary of Horry’s “string of questions,” and Drewry was thrown a lifeline by the prosecuting counsel: “Assuming a person to have committed a number of robberies, and afterwards shot a policeman when about to be apprehended, would you consider that an act of insanity? — Certainly not.”[18] Or, if the online Proceedings of the Old Bailey reports this exchange more accurately, Horry undermined his own case by asking: “Supposing him to exhibit the symptoms of insanity named, should you consider his going away from a policeman, having committed robberies, was an act of insanity or consciousness?” To which he received the firm answer “An act of consciousness.”[19] Horry must by then have seen the inevitable outcome: following an impassioned speech to the jury, something that would have been impossible just six years earlier,[20] the jurors consulted “for about a minute” before pronouncing the defendant guilty.

Thomas Cooper, who appeared still to be suffering from the poison he had taken soon after he killed Daly, was hanged outside Newgate on Monday 4 July 1842. In an obvious comparison to the execution of Daniel Good, who had been hanged on 23 May, The Morning Post reported a much smaller crowd than normal, because “the crime for which this offender [Cooper] suffered was not one of a character calculated by the circumstances attending it to excite that curiosity in the public mind that a murder in which there had been concealment, mutilation, and mystery never fails to give rise to.”[21]

Remembering PC Daly

At the time of his death PC Timothy Daly was 45 years old, married but without children. Irish by birth, he had served in the Metropolitan Police since its inception in 1829. Stationed at Islington throughout his career, he was apparently much respected by local people and loved by his fellow constables. A few months before his death “some influential parishioners exerted themselves to obtain for him a lucrative situation in that parish, in which they almost succeeded.”[22] Daly was undoubtedly a good policeman, and heroic, but he was also incautious: it was revealed at Cooper’s trial that Daly had several times told him that he did not believe the guns were loaded.[23] However, he sprang at him even after Mott had been shot. Given the brave way in which Daly, Moss and Mott approached the armed man, it seems safe to say that the early Victorian police, ably supported by civic-minded civilians, was well on its way to gaining the popular support that police historians note as a feature of the growing professionalism of the ‘new police’.[24]

Images

Main image: “Cooper shooting the policeman”, Trial of Cooper for the Murder of Timothy Daly, at Highbury (published by E. Lloyd, 1842). Harvard Law School Library, Historical & Special Collections, Trials Broadside 589, CC BY 4.0.

Thomas Wakley, esq., MP. Print by W.W., c. 1835–1852. Credit: Wellcome Library no. 9498i, CC BY 4.0.

References

[1] For examples of the latter, see for instance Martin Baggoley, Death on the Victorian Beat: The Shocking Story of Police Deaths (Barnsley: Pen and Sword History, 2018).

[2] Jennifer C. Gibbs, James Ruiz and Sarah Anne Klapper-Lehman, “Police Officers Killed on Duty: Replicating and Extending a Unique Look at Officer Deaths,” International Journal of Police Science & Management 16 (2014): 277-287.

[3] National Police Officers Roll of Honour, Metropolitan Police 1829–1899.

[4] Alan Moss and Keith Skinner, The Scotland Yard Files: Milestones in Crime Detection (Kew: The National Archives, 2006), pp. 23-30 notes the importance of the Good case as a stimulus to the creation of the Detective Branch in August 1842.

[5] Robert B. Shoemaker, “ The Street Robber and the Gentleman Highwayman: Changing Representations and Perceptions of Robbery in London, 1690–1800,” Cultural and Social History 3 (2006): 381-405 (p.403).

[6] There were over 40 highway robberies prosecuted annually in the years 1826–1828, but only 12 in 1829. Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0, March 2018), tabulating decade where offence category is highway robbery, after January 1750. Counting by offence.

[7] 6 Geo I c.23 (1719), An Act for the further preventing Robbery, Burglary, and other Felonies, and for the more effectual Transportation of Felons, section 8.

[8] The Ipswich Journal, 14 May 1842, 3.

[9] See for instance The Oxford City and County Chronicle, 7 May 1842, 3; Jackson’s Oxford Journal, 7 May 1842, 3; Dorset County Chronicle, 7 July 1842, 4.

[10] Dorset County Chronicle, 7 July 1842, 4.

[11] The Globe, 6 May 1842, 3.

[12] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0, 30 December 2020), June 1842, trial of Thomas Cooper (t18420613-1766); testimony of John William Howard. Hereafter OBP, trial of T. Cooper (t18420613-1766).

[13] The Ipswich Journal, 14 May 1842, 3.

[14] The sequence of events has been summarised from The Globe, 6 May 1842, 3 and OBP, trial of T. Cooper (t18420613-1766).

[15] Evening Mail, 9 May 1842, 1.

[16] The Ipswich Journal, 14 May 1842, 3.

[17] OBP, trial of T. Cooper (t18420613-1766), testimony of Edward Drewry.

[18] The Ipswich Journal, 25 June 1842, 4.

[19] OBP, trial of T. Cooper (t18420613-1766), testimony of Edward Drewry.

[20] 6 & 7 Will IV c.114 (1836), An Act for enabling Persons indicted of Felony to make their Defence by Counsel or Attorney.

[21] The Morning Post, 5 July 1842, 4.

[22] The Globe, 6 May 1842, 3; The Evening Chronicle, 6 May 1842, 3.

[23] OBP, trial of T. Cooper (t18420613-1766), testimony of John William Young.

[24] David Taylor, Crime, Policing and Punishment in England, 1750–1914 (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998), 78-87.