Guest post by Tim Stretton, 14 August 2021.

For centuries the English common law rules concerning married women’s rights—known by the shorthand ‘coverture’—restricted a wife’s ability to control real estate, own movable property, enter into contracts or participate in litigation without the cooperation of her husband. Yet, ongoing research confirms that a significant minority of women in broken marriages defied these restrictions and fought lawsuits against their husbands in equity courts. Chancery alone heard thousands of suits pitting spouse against spouse between 1500 and 1800.[1]

We know precious little, however, about how the women involved in these legal actions found and secured London-based lawyers and what advice they received. At first sight, a Chancery action from 1698 involving Mary Hockmore appears to offer a tantalizing exception, as it includes a lengthy deposition from a solicitor recalling his discussions with Mary a few years earlier.

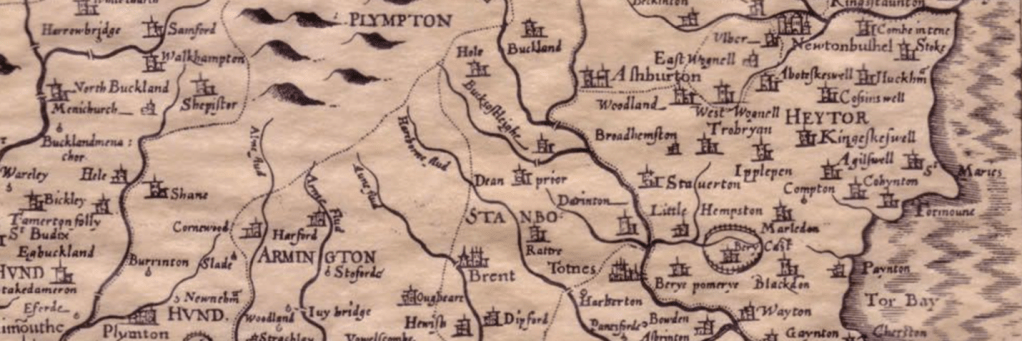

Mary Prestwood became Mary Hockmore when she married William Hockmore of Combeinteignhead in Devon in 1691 at the age of sixteen. The couple had four daughters in quick succession and seem to have lived amicably enough for a few years, but in 1695 the marriage began publicly disintegrating. According to Mary’s later account, William confessed to a long affair with a serving maid and as their marital relations soured he turned to beating Mary and criticizing her with ‘opprobrious words’. She said she put up with his behaviour for the sake of the family, but then in December William moved out. With no means of support, Mary left for Exeter a few weeks later, and after ensuring that her youngest daughter was safe with a wetnurse she travelled to London with her other children and two servants.

The marriage breakdown and its aftermath produced multiple lawsuits in equity, common law and ecclesiastical jurisdictions that have left hundreds of pages of documentation, but among the allegations and counter allegations are fascinating descriptions of legal interactions and procedures. For example, when William’s later attempts to serve process on Mary in London failed, because she refused to come to the door, he resorted to subterfuge. A witness described how at William’s bidding he had dressed in royal livery and pretended that King William,

‘desired her company at a play and was ready in the street with his coach to carry her to a playhouse, whereupon she came forth and this deponent served her with a citation, at which she was much surprised’.[1]

Of more significance for the subject of married women’s rights is the evidence of Mary’s supposed interactions with a lawyer. After travelling by coach from Exeter to London she arranged accommodation at the Angel Inn ‘on the backside of St Clements’ and then sought out Richard Stephens, a family friend from Devon at legal chambers in the Middle Temple. According to Stephens’ testimony, ‘she designed to bring a bill in Chancery for a separate maintenance and desired’ him ‘to be her solicitor’. He also helped her secure more permanent lodgings in Downing Street (not far from the famed current residence of the British Prime Minister).

Mary later accused Stephens of self interest and violence, and when he appeared as a deponent it was on behalf of her husband, so there are good reasons to discount his testimony. However, the scenario he described neatly encapsulates the shackles coverture could place on women in failing marriages. According to his deposition he began by asking Mary the cause of her separation, to which she replied ‘because her husband was jealous of her’ owing to the friendships she had made with other men. He then enquired ‘whether her said husband did ever beat her or abuse her or deny her those necessaries which were fit for her to have’, setting out the chief legal grounds for a separation suit in the church courts or an action for financial assistance in Chancery. In later pleadings Mary described William’s violence against her in excruciating detail, but according to Stephens she answered his first question by declaring that William had not beaten her, ‘for that she was able to beat two of him’. Furthermore, on the question of necessaries, ‘he could not deny her anything she had a mind to have’ because ‘she received all the profits of his estate’. Faced with these clear assertions of female independence, Stephens said that he had ‘advised her that she had no just grounds for a bill in equity as this deponent conceived, and withal advised her to return back again into the country to her husband’.

If Stephens concocted these exchanges at William’s bidding, to clear him of accusations of wife beating and financial deprivation, the pair chose a curious fiction to fabricate, given how blatantly it undermined William’s standing and reputation as a husband and patriarch. But regardless of their factual accuracy, his words confirm the depressing reality that women who presented themselves as victims of abuse might have opportunities to secure legal remedies, but that an independent woman who claimed to be physically stronger and more competent and resourceful than her husband had no realistic prospects of gaining officially sanctioned relief from an unhappy marriage. And Mary did not, at that time, attempt to bring a suit against her husband in Chancery.

Instead of returning to the family home of Buckland Baron, Mary apparently convinced Stephens to travel there on her behalf, to ‘endeavour a reconciliation between her’ and William on her own terms. We know that Stephens met with her husband in the presence of her brother, Sebastian Prestwood, and two local judges and then returned to London with Sebastian to convince her to reconcile.

Mary consented to return to Devon on condition that William sign articles of agreement with her and named trustees. Under the terms of these articles, executed on 10 April 1696, William promised he ‘would from henceforth and at all times then after kindly receive and take into his care and protection’ his wife Mary ‘and maintain her according to her degree and quality and treat her civilly’. Mary also demanded that he enter into covenants to raise £2500 ‘for the daughters he then had or should have by the said Mary Hockmore his wife’, to supplement the £1500 already secured for this purpose in the couple’s marriage settlement. Most important of all, from Mary’s perspective, William accepted that ‘if there should be a second separation’ then Mary was to have her jointure lands ‘for the maintenance of herself and children’.

In theory only the Church courts could order a marital separation, but Stephens never mentioned advising Mary to follow this path. Instead, Mary effectively brokered her own private separation by having her husband enter into a contractual agreement resembling a modern ‘pre-nup’. She did this by employing a common law instrument, articles of agreement set down in a deed or tripartite indenture to which she was a full party. This allowed her to inoculate herself against certain effects of coverture by guaranteeing income for her sole and separate use without interference by her husband, in the event that the reconciliation should fail.

And fail it did. The subsequent separation envisaged in the agreement duly occurred, with Mary alleging that in July William beat her so badly that she could not show herself in public. Once again William moved out and once again Mary sought refuge for her own safety. William told a different tale, alleging that when the British Fleet was anchored off Torbay in 1696 Mary had seduced, or been seduced by, naval and army officers who dined and billeted at the house. According to his account she became a serial adulteress, on one occasion locking a chamber door against him as she climbed into bed with one woman and two men during a wild night when a fiddler played a loud rendition of ‘The Devil is a Cuckold’.[3]

Mary enjoyed her hard won economic independence for a few months, but then the precarious nature of her situation became clear. William developed ‘buyer’s regret’ over the deed he had signed and challenged it on the grounds that she had failed to meet two of its terms: that she ‘should live and abide with her father George Prestwood esq or live at her jointure house Buckland Baron’ and that she should ‘not contract debts on her husband to bring him into any law suits or molestation’.[4]

Mary had contracted debts in William’s name because she had no access to other funds and she sued him in Chancery to have the settlement enforced. He, in turn, began a counter suit to have it revoked. Her suit faltered, undone by those accusations of adultery, but William persisted with his, renewing it in 1698 and adding the couple’s daughters as defendants. For good measure he also sought a church court separation, even though the couple had long lived apart, almost certainly with the goal of undermining Mary’s jointure and dower rights to property in addition to those guaranteed by the articles of agreement. He was successful in both actions. In February 1699 church officials passed a definitive sentence of ‘divorce’ or separation from bed and board on the grounds of adultery and in May 1701 the Lord Chancellor issued a final Chancery order that the articles of agreement be delivered up to William ‘to be cancelled’. Mary died a few years later and her final movements remain shrouded in mystery. But for a few short months she stood her ground and used legal advice and a carefully worded deed to challenge the patriarchal status quo.

cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Derek Harper – geograph.org.uk/p/6179730

_______________________________________________________

About the author: Tim Stretton has a law degree from the University of Adelaide and works as a Professor of History at Saint Mary’s University in Canada. His publications on women’s rights include Women Waging Law in Elizabethan England (Cambridge UP, 1998) and (with Krista Kesselring) Married Women and the Law: Coverture in England and the Common Law World (McGill Queen’s UP 2013) and Marriage, Separation and Divorce in England 1500-1700 (Oxford UP, forthcoming). He is currently completing a book on the Hockmore case.

Feature image: The Court of Chancery, c. 1725, by Benjamin Ferrers, © The National Portrait Gallery, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

References:

[1] See Maria Cioni, Women and Law in Elizabethan England with Particular Reference to the Court of Chancery (Garland, 1985); Tim Stretton, Marital Litigation in the Court of Requests 1542-1642 Camden 5th series vol. 32 (Cambridge UP, 2008); Emily Ireland, ‘Married Women’s Litigation in the English Court of Chancery, 1698-1758’, (unpublished PhD, University of Adelaide Law School, 2020); K.J. Kesselring and Tim Stretton, Marriage, Separation and Divorce in England 1500-1700 (Oxford UP, forthcoming).

[2] The National Archives [TNA], C 22/555/14, deposition of John Whitborough of Exeter, Devon. Spelling, here and in other quotes, has been modernized.

[3] TNA, C 22/555/14, deposition of Joan Angel of Little Hempston Devon.

[4] TNA, C 22/555/14, Deposition of Richard Stephens.