Posted by Krista J. Kesselring, 26 July 2022.

Some myths about the past float entirely free of the evidence, but some have just enough grounding in the documentary record to be particularly persistent. Witchcraft is mired with myths of both sorts. Historians repeatedly and seemingly in vain point out that the phenomenon of ‘witch hunting’ was not so much medieval as early modern – it corresponded with the age of Shakespeare and early science more so than the supposedly superstitious or saintly Middle Ages. They note that much of the energy behind the fears and trials came from educated, elite commentators not some uneducated, illiterate rabble, and from secular authorities, physicians, and lawyers at least as often as from churchmen. (King James VI/I’s witch-treatise Daemonologie, first published in 1597, is a prime example.) While patriarchy pervaded the proceedings – the majority of the condemned in England as in many other places were women – specialists point out that it didn’t do so in some cartoonishly simple, straightforward way; other women figured prominently among the accusers and supposed victims and helped keep the fears alive. Most cases we know about focused on the harm a supposed witch did, not witchcraft itself. Not every ornery or obstreperous woman found herself on trial. And juries acquitted somewhat more than half of the people who were formally accused. But yes, some of the people who saw themselves as witches or were seen as such by others did face death (though, in England, by execution like that of a common criminal rather than that of a heretic, inflicted not with fire but a noose): in England, perhaps some 500 people died undeserved deaths for witchcraft from c. 1560-1684.[1] These deaths demand attention. But so, too, do the bits of the past that don’t correspond with the stories so often told about it, not least the doubt and decency that kept the death count from being higher than it was and that can be discerned in the evidence when we look for it.

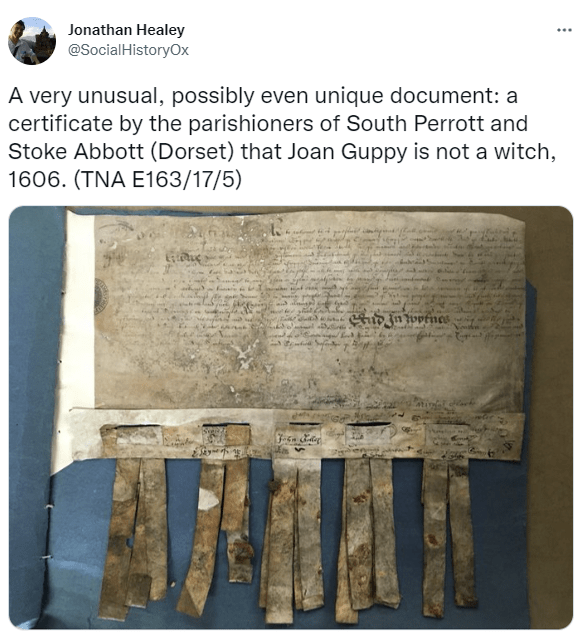

I am particularly interested in the doubt and decency: the (contemporaneous) pardons recommended by judges, the high numbers of acquittals given by local jurors, and the factors that kept so many suspicions from ever getting to the dangerous drama of a trial. As such, a tweet from Jonathan Healey some time ago caught my eye:

A 1606 certificate from a group of her neighbours attesting that one Joan Guppy, said by some to be a witch, was no such thing: that is indeed an interesting document. To their knowledge, they wrote, Guppy had never hurt any person by means of enchantment, sorcery, or witchcraft. ‘Contrariwise’, they note, ‘she hath done good to many people as well in curing of diverse people of wounds and such like things’. They left their marks, signatures, and seals on a document sent to some of the highest officials in the realm to affirm that Guppy had long lived among them with a ‘good name and fame’.

Back in the archives this summer after being kept away far too long by Covid, I was able to call up records from a court case that preceded this remarkable neighbourly intervention.[2] The case began with Joan Guppy’s own bill of complaint to the Court of Star Chamber. She and her husband Thomas – a married woman could not launch a case on her own – petitioned the court for redress after what they described as a ‘barbarous’ attack upon her as she rode from South Perrott to the market in Crewkerne one June day in 1605. They said that a group of maliciously-minded people had plotted, conspired, and confederated to attack Joan, calling her a witch and baying for her blood. They pulled her from her horse and riotously tore at her, Joan said, to the great peril of her life and her good name.

A partial picture and transcription of Joan’s bill of complaint is on The National Archives’ site amongst its educational resources for classroom use. On its own, it seems to confirm some of the worst views of neighbourly suspicion and violence. But people who have worked with Star Chamber bills know to be suspicious of their claims of violence: the standard statement that a plaintiff’s opponents were ‘armed and arrayed with long piked staves, swords, daggers, and other warlike weapons’ was a fiction or phrase of art used to get a case heard by this particular court. It appears in complaints about all sorts of wrongs, in the overwhelming majority of which no such ‘warlike weapons’ actually appeared. Even without any long experience of Star Chamber records’ peculiarities, reading the next clause about the particular weapon used – ‘great overgrown brambles’ – should prompt some pause, as might the fact that the complaint only specifies four attackers by name, not the armed throngs implied in the standard legal verbiage of the bill.

While some of the language in the bill of complaint is standard and fits common expectations, turning to the full file of court documents reveals a few unexpected elements. Accompanying the bill of complaint are two written answers from the defendants: one done jointly by Robert Gibbs and Richard Newman, the other done by Judith Gibbs and Margaret Abington. A list of questions to be asked of witnesses follows, as do the depositions of the two men accused. These documents clarify that the Gibbs and Abington were siblings and suggest that Newman was scarcely involved, more a bystander briefly drawn in than an active participant. (He thought Joan had named him as a defendant to avoid having him testify as a witness.) And the story they tell is quite remarkable, especially as narrated in the women’s answer. Judith, the younger sister, claimed the central role. And she didn’t deny the confrontation at all, though she described it quite differently than Joan had—no conspiracy, no warlike weapons, no intent to do serious harm. Rather, she said, she had talked her siblings into helping her get relief from a woman she thought had bewitched her, by scratching her for a few drops of blood.

In Judith’s telling, she had been sick for over three years, ‘tormented with a strange swelling and hardness within her body’, with her bowels so bloated ‘she should have burst’. She had turned to learned medical professionals to alleviate her suffering. When none of their treatments helped, the physicians opined that her illness must have unnatural causes. She then appealed to Joan Guppy, who had a reputation for being able to cure those who had been bewitched, both ‘Christian creatures and beasts’. Joan would take clothes from a person or hair from an animal, retreat to a secret chamber, use prayers or charms upon them, and then emerge to say ‘sometimes that they were bewitched, sometimes that they were overlooked, and sometimes that they were bruised or taken with the fairies or such like’. She would then sell her clients powders to lift the enchantment—in Judith’s embittered telling, Joan made great profit by selling her services to the ‘ignorant country people’. But when she appealed to Joan for help, Joan refused.

At that point, of course, Judith started to think that Joan was the one who had bewitched her. She reflected that Joan no longer came to church much, failed to participate in communion, and hadn’t been able to recite the Lord’s Prayer when called to do so. ‘Considering with herself the quality and profession of the said Joan Guppy and some effects that seemed to proceed from her’—that when she became displeased with neighbours their animals sometimes came to strange and sudden ends, for example—and thinking back to signs that Joan disliked her, Judith started to wonder if Joan’s talent in divination and doctoring in fact came ‘of some malignant spirit of sorcery, for of a good spirit it could not proceed’.

Judith turned to her brother and sister, sure now that her only relief would come from scratching Joan. ‘It is a common received opinion in the country that to scratch and fetch blood of such as do harm in that quality is a means to cure them that be hurt’, she noted. Seeing her desperation, Judith’s siblings agreed. They waited for Joan as she rode to market. Later insisting that they only meant to scratch Joan, they admitted that the encounter became a bit rough when Joan refused to alight from her horse and struck at them with her riding crop. Judith stabbed at her leg with a pin; sister Margaret grabbed a bramble from the roadside and scratched her face. Robert proved little help. Richard Newman, chancing by, intervened to ask what was going on and tried to direct the group to his master, a justice of the peace. But instead of following him to the local justice, once Joan was off her horse she ran into the nearby home of an aunt. The siblings left, thinking they had enough drops of Joan’s blood to achieve their ends.

And, indeed, in further defence of their actions, Judith insisted that for a while after the pricking, she did feel better, while Joan sickened. Judith noted other stories of Joan curing by taking an illness upon herself and then transferring it to another creature, or of curing her own earlier ailments by passing them on to people such as Judith. And a transfer happened yet again, Judith said. Hearing of their attack on Joan, the siblings’ parents became angry and ‘bitterly reproved’ them all. Once Judith expressed remorse, her illness—and Joan’s health—returned.

With renewed faith in her assessment of Joan Guppy, Judith now challenged the court to dismiss the complaint against her. Was such an insignificant episode as this pricking really to take up the time of such an important court? Was it even worthy of punishment at all, she asked? She then played what she likely hoped to be her trump card: she knew Joan was a witch because ‘the king’s most excellent majesty in his book against witches entitled the Daemonologie hath set forth that the things abovesaid practiced by the said Joan are the very qualities and marks whereby to know a witch or a sorcerer’.

Whether Star Chamber’s judges decided to punish Judith and her siblings isn’t clear—no sign of them having imposed a fine appears in the usual financial accounts, suggesting that they did not or that the case didn’t proceed to judgement. Some local investigation of the competing claims continued—Joan and Thomas Guppy seem to have launched the case in the central court to influence local action that started after they complained to their neighbouring JPs—and the group of neighbours produced their certificate that Joan was no witch. We do know that Joan lived on for years yet, named in her husband’s 1626 will, alongside two daughters born after the episode.[3]

This is just one case, true, but it shows yet again that neighbours could be cautious more so than credulous, more suspicious of claims that a woman was a witch than of the woman herself. And they looked for ‘evidence’—even Judith, Joan’s accuser, tried weighing evidence for her suspicions. While wrong in her conclusions, she interpreted actions and events in part by drawing upon theories provided to her by learned physicians and the king’s published writings. We see people not automatically acting upon signs of supernatural powers but distinguishing between the harmful and the helpful, the neighbourly and unneighbourly. (Newman, the bystander-cum-defendant, testified that Guppy was widely known to use enchantments and charms and suspected to be a witch, an interesting distinction.) One piece of evidence, read on its own—Joan’s bill of complaint—might seem to support common misperceptions of superstitious mobs bent on killing wise women and healers; read in the round, though, the evidence points to a fair degree of doubt and decency.

Joan Guppy’s neighbours were more discerning in their use of evidence than we sometimes allow people in the era of the witch-hunts to have been. Discernment, doubt, and decency might be less enthralling topics than death, but to understand the phenomenon of the witch-hunts, they deserve their due. We might need to be more discerning in our own use of evidence, and allow it to disrupt deeply cherished myths about the past. We might even want to ask why these myths persist and what work they do in the present.

Cover image: John Pettie, An Arrest for Witchcraft in the Olden Time, 1886, © Wolverhampton Arts and Heritage, www.wolverhamptonart.org.uk, used under a Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike License 3.0.

Notes:

[1] For the acquittal rates, see James Sharpe, Instruments of Darkness: Witchcraft in England, 1550-1750 (London, 1996), pp. 111-113. Of 474 people indicted for witchcraft on the Home Circuit from1560-1701, juries acquitted 56% of the accused. Some of the others faced punishments less than death; ultimately, 22% (104/474) were executed. For scholarly studies of witchcraft in England and beyond that address the points raised in this paragraph, see also, e.g., Christina Larner, Witchcraft and Religion: The Politics of Popular Belief (Oxford, 1984); Sharpe, The Bewitching of Anne Gunter: A Horrible and True Story of Deception, Witchcraft, Murder, and the King of England (London, 2000); Sharpe, ‘Witch-hunting and witch historiography: some Anglo-Scottish comparisons’, in Julian Goodare, ed., The Scottish Witch-Hunt in Context (Manchester, 2002), pp. 182-97; Marion Gibson, Early Modern Witches: Witchcraft Cases in Contemporary Writing (London, 2000); Brian Levack, The Witch-Hunt in Early Modern Europe (Harlow, 2006); various works by Malcolm Gaskill, including ‘Witchcraft and Evidence in Early Modern England’, Past and Present 198 (2008), 33-70; Garthine Walker, ‘The Strangeness of the Familiar: Witchcraft and the Law in Early Modern England’, in Angela McShane and Garthine Walker, eds., The Extraordinary and the Everyday in Early Modern England (Basingstoke, 2010), pp. 105-24; Orna Alyagon Darr, Marks of an Absolute Witch: Evidentiary Dilemmas in Early Modern England (Farnham, 2011); essays in both Levack, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Witchcraft in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America (Oxford, 2013) and Johannes Dillinger, ed., The Routledge History of Witchcraft (London, 2021); etc.

[2] For what follows, see The National Archives (Kew), STAC 8/149/24, Guppye v Gybbes.

[3] The National Archives (Kew), PROB 11/150/174, Will of Thomas Guppie of South Perrott, Dorset (28 October 1626).

Reblogged this on Calculus of Decay .

LikeLike

Thank you!!! Wonderful read

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] modern medical marketplace.[12] The case also suggests that with suspected poisonings, as with witchcraft, doubt sometimes prevailed: faced with weak evidence, the trial jurors who held Moyle’s life in […]

LikeLike