Posted by Krista J. Kesselring, 10 October 2022.

‘The Queen is dead, long live the King.’

When Queen Elizabeth II died, media commentators assured audiences that by ancient tradition her eldest son had instantly become monarch in her stead. In Britain and throughout the Commonwealth, proclamations confirmed King Charles III in a status said already to be his, well before any oath-taking, anointing, or other coronation rite, let alone any conciliar, parliamentary, or popular election. Whether enthusiastic about the new king or not, many people accepted this characterization of the accession. And, the media frenzy apart, no great disorder descended upon the ‘demise of the Crown’ or of the woman who had worn it. Such was not the case at the end of the first Elizabethan age.

‘There is now no law.’

When Queen Elizabeth I died on 24 March 1603, after a 44-year reign and with no child to succeed her, the men who had served as her councillors proclaimed her Scottish cousin, King James VI, to be ‘at one instant’ the new sovereign of England in her place.[1] They urged officials appointed under the late queen to stay in their posts, to preserve the ‘public peace’ if no longer the queen’s, and hailed James as king before he had even heard the news. But many people who accepted that James would be king did not think he was just yet. Throughout the realms that Elizabeth had ruled, many people professed to believe themselves in an interregnum, a period between two reigns in which the laws of no lord but God applied.

In some such examples, one suspects a bit of post-hoc excuse-making by people simply taking advantage of the disruptions to office-holding that followed the death of a monarch or anticipating the general pardon that usually celebrated the coronation of their successor. The Anglo-Scottish borders saw some of the most widespread disorder after the queen’s death. The Grahams and other clans of border reivers embarked on the notorious ‘busy week’ or ‘ill week’, raiding and seizing thousands of sheep and cattle. When the new king moved to restore order with threats to deport the Grahams en masse, one petition for mercy maintained that:

some among us of evil and corrupt judgement did persuade us that until your majesty was a crowned king within the realm of England that the law of the said kingdom did cease and was of no force, and that all acts and offences whatsoever done and committed in the meantime were not by the common justice of this realm punishable, by force of which malicious error put into our heads, as deceived men, and believing …those gross untruths, we did most injuriously run upon your majesty’s inland subjects and did them many wrongs.[2]

Maybe they really thought so; maybe not.

Some such statements suggested qualms about this specific succession, with the arrival not just of a new monarch but a foreign one, and a Scot at that. In Essex, the tailor Bartholomew Ward opined ‘it were a pity that a foreign king should be king’ and that ‘there were as wise men in England to have been king as the king of Scots’. He thought himself free to voice his objections, though, as ‘the king that was proclaimed was not king of England till he was crowned…and there was no law ‘til our king’s majesty hath enacted a parliament but God’s laws’.[3]

Yet, more may have animated some assertions of a lawless interregnum than simple excuse-making or distrust of a foreign king. Shortly after the proclamation of King James’s accession, a blacksmith insisted that ‘we neither had a prince nor laws’ until the coronation. A butcher agreed that James ‘is no king ‘til he be crowned’. David Cressy collected these and similar statements from criminal court archives, arguing that ‘a legalistic antinomian current recurs in these outbursts, suggesting a popular constitutional literacy that confused the king’s rights by accession with the legitimacy afforded by his coronation’.[4]

In his studies of crowd protest and collective action, John Walter gathered similar tales of the efforts of ‘plebeian constitutionalists’, seeing the stories as evidence of ‘popular understandings of and protesters’ ability to exploit ambiguity within the law’.[5] A group of people in Cambridgeshire tore down an enclosure shortly after Elizabeth’s death; according to the target of their ire, they ‘persuade themselves of a kind of interim or intermission of government and in respect thereof hope to escape the punishment due’.[6] A group of women in Nether Wyresdale who destroyed an enclosure in April 1603 had a trifecta of excuses for lawlessness at the ready: the supposed immunity to criminal prosecution of wives, the license traditionally allowed for misbehaviour on Shrove Tuesday, and, above all, the death of the queen which meant ‘they might then do the same without danger of law, for that there was now no law in force’.[7]

Such assertions of law’s absence in the gap between the old queen’s death and the new king’s coronation (or first parliament) came not just from people who might readily claim ignorance of the laws. A lawyer then in the Norwich gaol tried to talk his companions into escaping, reportedly saying that the queen’s death had produced ‘an interregnum, a lawless time, and that it was no offence to break prison at this time’. Attorney General Coke observed that, as a lawyer, the man should have known better and thus his fault was all the greater.[8]

Some Catholic community leaders tried similar arguments. In Ireland, Catholics in several towns re-consecrated church altars, restored the Mass, and reclaimed the streets with religious processions. They seemed to think that they would have the new king’s support and were just getting a head start. When it proved otherwise, magistrates of one town blamed the ignorance of the common people and said ‘that after the death of their queen they thought it not against the law to profess their religion publicly, ‘til the king’s coronation’. The ‘chiefest citizens of Waterford’ also apologized, saying that ‘they had only taken the benefit of the time, by the death of the queen to use the liberty of their consciences’. The English deputy in Ireland, Lord Mountjoy, suggested as much to the mayor of Cork: ‘it may be you have rashly and unadvisedly done this, upon some opinion of the ceasing of authority in the public government, upon the death of our late sovereign’. He in turn relayed the suggested excuse back to the king’s chief minister, saying that the Catholics had acted only to ‘declare their religion to his Majesty and the world, in that time between two reigns, wherein they suppose it lawful or less dangerous’.[9]

In England, the day after Elizabeth died, Sir Henry Carew went to his parish church to declare the Elizabethan religious service dead, too. He wanted the keys to lock the doors shut until the king could return the English to communion with the true Church. Dragged into the Court of Star Chamber, Carew tried invoking Magna Carta’s provisions to challenge the proceedings, but to no avail. Though Carew had expected the new king’s support, he found the king’s judges united against him in denouncing his offence against God and His service, against the late monarch and the new, and against the very state itself. According to one court observer, the judges declared that Carew had offended not just Elizabeth and James but also something bigger, less tangible but longer-lasting. They insisted that ‘the King’s Majesty, in his lawful, just, and lineal title to the Crown of England, comes not by succession only, or by election, but from God only (so that there is no interregnum, as the ignorant doth suppose, until the ceremony of coronation)…[T]he very instant that the breath was out of her Majesty’s body, King James was lawful and rightful king’.[10]

All this talk of an ‘interregnum’ is quite curious. According to lawyers and historians, the ‘abstract physiological fiction’ that the king never dies, and its corollary that a new monarch succeeded at the instant of their predecessor’s demise, had appeared by the late thirteenth century. In 1270, the French King Philip III assumed power and dated his reign not from his coronation but from his father’s death, with both men then absent from the kingdom. Two years later the English did the same, or very nearly, with Edward I – then off on crusade – declared to have assumed full power from the moment of his father’s burial. Thenceforth, as Ernst Kantorowicz noted in his classic study of the concept of ‘the king’s two bodies’ – one natural, one artificial and political – a new king’s ‘true legitimation was dynastical, independent of approval or consecration by the church and independent also of election by the people’. [11] In theory, then, the impossibility of an interregnum should have been settled long before James took Elizabeth’s place on the English throne.

But while Kantorowicz traced the ‘mystic fiction’ of the king’s two bodies back to the Christologically-inflected musings of thirteenth-century theorists, he found the fullest, clearest statements of the belief and its pragmatic implications in the writings of late Tudor lawyers. In one case, for example, lawyers debated whether the Duchy of Lancaster was owned by ‘the Crown’ or by the monarch in their private capacity. (In this case, jurists decided the latter, something perhaps to be borne in mind by people who misjudge how much property would go to the public purse if monarchy was abolished.) Lawyers described the Crown as an undying corporation sole. They returned repeatedly to issues surrounding when and in what ways the person wearing the crown and ‘the Crown’ were the same or separable.[12] As Cynthia Herrup has observed, it is surely no accident that the ‘two-body fiction’ came to prominence in the half-century when the country was ruled by ‘disabled’ monarchs, an underage boy and then two women, and when most of the likely successors were female. ‘The argument that since the king never died, the individual characteristics of the prince were no disqualification from ruling was only one of several ways to argue support for women kings’.[13] That the king had an artificial body that did not die was an old fiction, but one still evolving.

Moreover, whether they knew it or not, the late queen’s subjects had some high-level legitimation in thinking about interregnums. Back before Elizabeth’s councillors could be confident that her Protestant cousin James would succeed her, they feared that James’s Catholic mother Mary might do so—and that Mary’s adherents might hasten the day by killing the queen. To avoid such a fate, Elizabeth’s chief advisor, William Cecil, and other prominent figures crafted plans to allow an ‘interreyn for some reasonable time’: in the event of Elizabeth’s untimely death, a great council would govern the country and recall parliament to select a suitable successor.[14] They concocted their plans for an interregnum to avoid lawlessness (as they saw it), not to license it, but after James’s accession it was best to attribute any such talk to popular error and ignorance. Evidently, though, the possibility of an interregnum was not simply a fantasy of ‘plebeian constitutionalists’ alone.

At the turn to the seventeenth century, then, quite a few people – ‘ignorant’ and otherwise – thought a claimant to the throne needed something more than birthright to become fully owed their obedience. The insistence of some of them upon the lawlessness of the resulting interregnum might sound a bit like the pseudolegal arguments of fringe political actors today – like those that invoked Magna Carta to fight public health protections at the height of the pandemic.[15] But then, perhaps the arguments of these ‘plebeian constitutionalists’ seemed no stranger or less rational than practices that rested on talk of kings who never die and monarchs who had two bodies – the ‘mystic fiction’ of the Crown.

Images:

Cover image: The coronation chair, from D. Hume, The History of England (1859), via Wikimedia Commons.

Funeral procession of Queen Elizabeth I, from Add. Ms. 35324, courtesy of the British Library.

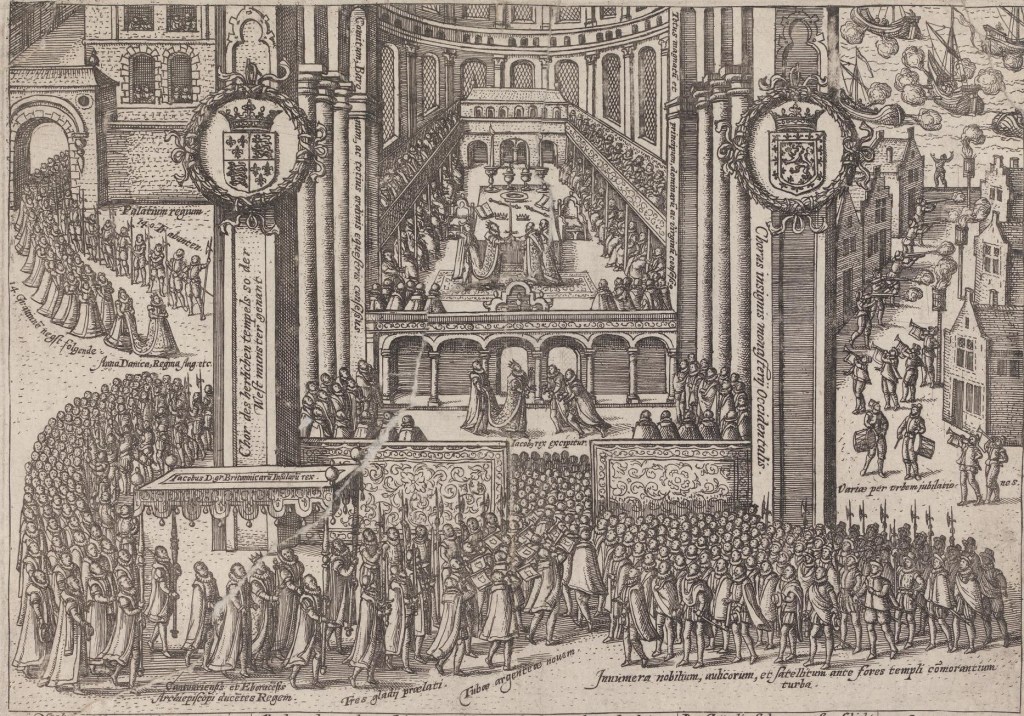

A 1603 engraving of the coronation of King James VI as King of England, unknown artist, via Wikimedia Commons.

Painted genealogy of King James’s English ancestry, c. 1603, unknown artist, via Wikimedia Commons.

Portion from an engraving of Queen Elizabeth’s funeral monument, unknown artist, courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, shared on a CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 license.

St. Edward’s Crown, from Francis Sandford, The History of the Coronation of the most high, most mighty, and most excellent monarch, James II (1687), via Wikimedia Commons.

Notes:

[1] John Hawarde, Les Reportes del Cases in Camera Stellata, 1593-1609, ed. W.P. Baildon (1894), p. 179.

[2] Cumbria Archive Service, DPEN/216, f. 60d, petition of Walter Graham and 78 others to the king. ‘Ill week’ is discussed in Catherine Ferguson, ‘Law and Order on the Anglo-Scottish Border, 1603-1707’, St. Andrews University PhD dissertation, 1981.

[3] J.S. Cockburn, ed., Calendar of Assize Records: Essex Indictments. James I (1982), no. 3, and David Cressy, Dangerous Talk: Scandalous, Seditious, and Treasonable Speech in Pre-Modern England (Oxford, 2010), p. 93.

[4] Cressy, Dangerous Talk, p. 93. For an additional case, see STAC 8/117/8, in which the plaintiff alleged that a local foe challenged him to a fight and said that with the Queen dead, ‘there was then now no law or justice to punish or right any…’

[5] John Walter, ‘”Law-mindedness”: Crowds, Courts, and Popular Knowledge of the Law in Early Modern England’, in Michael Lobban, Joanne Begiato, and Adrian Green, eds., Law, Lawyers, and Litigants in Early Modern England: Essays in Memory of Christopher W. Brooks (Cambridge, 2019), p. 175; for the ‘plebeian constitutionalists’, see John Walter, ‘The “Recusancy Revolt” of 1603 Revisited, Popular Politics, and Civic Catholicism in Early Modern Ireland’, The Historical Journal, 65 (2022), 249-274 at 258.

[6] Walter, ‘Law-mindedness’, p. 176, quoting The National Archives, Kew [TNA], STAC 8/152/2.

[7] Walter, ‘Law-mindedness’, p. 176, quoting TNA, STAC 8/203/30.

[8] ‘Cecil Papers: 5 March 1603/4’, Attorney General Edward Coke to Robert Cecil, in Calendar of the Cecil Papers in Hatfield House: Volume 16, 1604, ed. M S Giuseppi (London, 1933), p. 37. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-cecil-papers/vol16/pp37-48.

[9] See Walter, ‘The “Recusancy Revolt” of 1603 Revisited’, 249-274 and Anthony J. Sheehan, ‘The Recusancy Revolt of 1603: A Reinterpretation’, Archivium Hibernicum, 28 (1983), 3-13. Quotes from TNA, SP 63/215, ff. 75, 121-121d and Fynes Moryson, An Itinerary (1617), p. 288, cited in Walter, p. 259.

[10] Hawarde, Camera Stellata, pp. 163-4. Carew was fined the enormous sum of £1000 and committed to the Fleet during the king’s pleasure, whence he repeatedly petitioned for release over the coming months. [See TNA, E 159/425 m. 117 for the fine and the Cecil Papers, vol. 15, p. 101 (23 May 1603), p. 127 (7 June 1603), and p. 209 (24 July 1603) for the petitions.] The case is also mentioned briefly in W. Hudson, ‘A Treatise on the Court of Star Chamber’, in Collectanea Juridica, ed. F. Hargrave (2 vols, London, 1792), ii. 1-240, at p. 4.

[11] Ernst Kantorowicz, The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology (Princeton, NJ, 1957), pp. 328-330.

[12] Kantorowicz, King’s Two Bodies, ch. 1; see also F.W. Maitland, ‘The Crown as Corporation’, Law Quarterly Review, 17 (1901), 131-146, and John Baker, Reports from the Notebooks of Edward Coke, vol. 1 (London, Selden Society, 2022), p. cli, fn. 79.

[13] Cynthia B. Herrup, ‘The King’s Two Genders’, Journal of British Studies, 45.3 (2006), 493-510, quotes at 495 and 502.

[14] See the classic essay by Patrick Collinson, ‘The Monarchical Republic of Queen Elizabeth I’, Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester, 69 (1987), 394-424; amongst the documents cited by Collinson that set out plans for an interregnum, see esp. TNA, SP 12/176, ff. 71-80 for Thomas Digges’s proposal.

[15] On pseudolaw, see, e.g., Colin McRoberts, ‘Here Comes Pseudolaw, a Weird Little Cousin of Pseudoscience’, Aeon, 21 March 2016 [accessed 28 September 2022]; Colin McRoberts, ‘Tinfoil Hats and Powdered Wigs: Thoughts on Pseudolaw’, Washburn Law Journal, 58.3 (2019), available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3400362; and Donald Netolitzky, ‘Lawyers and Court Representation of Organized Pseudolegal Commercial Argument [OPCA] Litigants in Canada’, UBC Law Review 51.2 (2018), available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3237255 (My thanks to Shirley Tillotson for this reference.)

[…] last post focused on the popular belief in a lawless period between the death of Queen Elizabeth I and the […]

LikeLike