By Cassie Watson; posted 22 June 2023.

When we come across reports of children found dead with one or both of their parents, yet the police are not seeking “anyone else” in connection with the incident, the logical assumption is that it is a tragic case of family murder.[1] Criminological, psychological and psychiatric literature has tended to focus on classifying such acts of child murder or filicide by type, initially using categories identified by forensic psychiatrist Phillip J. Resnick in 1969.[2] The term ‘family annihilator’ was coined in 1987 to describe a specific type of filicide characterised by the deliberate killing of one’s own child or children, a phenomenon that has become more visible since the 1980s.[3]

Homicide was and is a largely male-perpetrated crime,[4] despite the fact that since the early nineteenth century women have tended to be statistically over-represented among child-killers.[5] Newborn child murder, or infanticide, was typically committed by young, unmarried women, for example.[6] But family annihilation is much more closely associated with men. Criminologists Yardley, Wilson and Lynes identified four different types of male British family annihilators, noting that “What seems to link each of the subcategories … is masculinity and the need to exert power and control in situations when the annihilator feels that his masculinity has, in some way, been threatened.”[7] This might not seem too surprising to crime historians.

In the remainder of this post, I consider the links between gender and filicide in the nineteenth century by examining a particular group of paternal child murderers: those who used poison. Unlike other methods of murder, poisoning had long had an especially negative association with deviousness and prior planning, and was thought to be unfair in that victims could not fight back against what they could not see. As the number of cases notified to the authorities began to rise in the late 1820s, public anxiety about the prevalence of murder by poison began to grow. By the 1840s, Britain was in the midst of a poison panic: the fear was fed by well-publicised reports of trials and executions which, while not numerous, seemed indicative of the dangerous incidence of a unique type of homicide that was particularly difficult to prevent or detect.[8]

Characteristics of Victorian Fatherhood

At the same time that the incidence and fear of poisoning crimes was rising, the Victorian legal system adopted an increasingly harsh attitude to men who committed violence against women and other dependents. This was part of a wider cultural shift in notions of masculinity, towards an ideal that was more self-restrained and pacific in 1900 than it had been in 1800.[9]

Moreover, and specifically in relation to fathers who killed a child in nineteenth-century England, Jade Shepherd has shown that “attitudes towards paternal child-murder were more similar to those expressed in cases of female infanticide than has been supposed”: the crime was considered so contrary to expectations that it implied an act of insanity.[10] “A certain degree of sympathy” could be extended to fathers who killed for reasons linked to psychological emasculation — typically poverty, domestic troubles and drunkenness, all of which were reframed as forms of insanity. Such men were perceived as depressed, regretful and introverted. It was this combination of demeanour and apparent motivation that saved them from the gallows, while other men who did not meet these expectations were executed. According to Shepherd, “Press representations of child murder differed according to who committed the crime: insane paternal child-murderers tended to be described as pensive and quiet, whereas childless men were seen as savage beasts fuelled by passion.”[11]

Criminal Poisoning by English Parents, 1801-1905

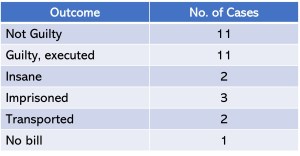

The figures to the left summarise the trial outcomes for 30 fathers accused of poisoning one or more of their own children. In the same period, 81 cases concerned children alleged to have been criminally poisoned by a mother, stepmother, foster mother or grandmother. These figures exclude individuals convicted for the murder of an adult but also suspected of killing their young children, such as William Palmer (1856) and Mary Emily Cage (1851). Of the 24 women who were actually found to be fully culpable, only seven were executed – four stepmothers in 1817, 1843, 1844, and 1873 (Mary Ann Cotton, Britain’s most infamous and prolific female serial killer); a grandmother in 1844; Rebecca Smith in 1849;[12] and Elizabeth Berry in 1887. Nine others had their death sentences commuted.

There was clearly a gender-based distinction made by juries, the judiciary and the Home Office in decisions about guilt and punishment: only 30% of mothers were found to be fully culpable (i.e. neither acquitted nor found to be guilty but insane), versus 53% of fathers; 37% of fathers were executed compared to just 9% of mothers. A much higher proportion of wives convicted of poisoning their husband was executed, 70% (23/33).[13]

The motivations for the poisoning crimes committed by parents were however largely similar, mainly money — to save cost, be rid of a burden, or to profit from a small insurance policy. Trial outcomes often hinged on whether the child in question was a newborn or a toddler, as murders of older children were much harder to justify on the grounds of insanity, for both mothers and fathers.

Fathers were however distinctive in one way: three of those in my database killed one or more of their children in an attempted family annihilation. This small group includes Arthur Devereux, who poisoned his wife and twin sons aged 2 years, but spared his eldest son Stanley, apparently in order to provide more for this boy. Such cases can be re-examined in the light of the modern criminological concept of the ‘family annihilator’, a majority of which — in late twentieth-century England — were found to emanate from psychological weaknesses in the father. I would suggest that financial difficulties were a more common factor in the nineteenth century.

The following case studies allow us to examine these gender-based distinctions in a little more detail.

The 1880s – Comparable Reactions?

In the late 1880s Elizabeth Berry (1855-1887) and George Horton (c.1852-1889) were both tried for filicide by Mr Justice Hawkins, a notoriously controversial and harsh judge who, while he held out no hope of a reprieve for Horton, refrained from making comments about his status as a father. The trial of Florence Maybrick, accused of poisoning her husband, was held in Liverpool in the same week as Horton’s; the judge in her case, Mr Justice Stephen, was soon accused of unfairness and bias due to his moral aversion to her status as an adulteress.[14]

We see a similar gender-based tenor in the comments made to Elizabeth Berry, who had poisoned her 11-year-old daughter for financial reasons.[15] But Horton, despite his guilt, managed to present himself as an acceptable version of Victorian masculinity: he confessed, he sought and received forgiveness, he cautioned his surviving children to lead productive lives, he displayed emotional anguish, and he confirmed that he had not touched alcohol for at least 18 months. Despite the calculated nature of his crime — the deliberate poisoning of his 7-year-old daughter to obtain £7 insurance money, the press accepted him as an appropriate example of Victorian masculinity, one who “walked to the scaffold firmly.”[16] In the end, the positive attributes of fatherhood and manliness seem to have outweighed the negative attributes of the stealthy poisoner.

Conclusion

Mothers who killed their own child were generally thought to be ‘mad or bad’, either suffering from mental disorders tied to a “fragile nervous system and unpredictable reproductive organs,”[17] or, like Elizabeth Berry, simply wicked. This assumption persisted throughout the twentieth century, when male child killers tended to be seen as “bad and normal” but their female counterparts as “mad and abnormal.”[18] What nineteenth-century cases of parental child poisoners seem to suggest is that the inherently cowardly and unmanly act of poisoning a defenceless child could be interpreted in much the same way that cases of female-perpetrated infanticide were, but without recourse to explicitly biological assumptions. It seems likely, therefore, that the psychological weaknesses associated with deviant masculinity and, indeed, deviant femininity, might be further explored in a broader study of family annihilators, beyond those who used poison or committed their crimes in the late twentieth century.

Images

Main image: A family (two adults and two children) lying dead in a room in their house as a result of poison gas emitted from an aeroplane flying overhead. Colour lithograph. Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, between 1920 and 1929. Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

The Execution of Rebecca Smith at Devizes, 1849. Unknown artist. Photo credit: Wiltshire Museum. Available at Art UK; Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike licence (CC BY-NC-SA).

Arthur Devereux. Evening Express and Evening Mail, third edition, 29 July 1905, 3. The National Library of Wales, Welsh Newspapers. The copyright status or ownership of this resource is unknown.

References

[1] See, for example, an incident reported in London on 19 June 2023.

[2] Phillip J. Resnick, “Child Murder by Parents: A Psychiatric Review of Filicide,” American Journal of Psychiatry 126 (1969): 325-334. Using 131 cases of child murder, Resnick classified filicide according to apparent motive: altruistic, acutely psychotic, unwanted child, accidental, and spousal revenge. He concluded that the high frequency of altruistic motives distinguished filicide from other homicides.

[3] Elizabeth Yardley, David Wilson and Adam Lynes, “A Taxonomy of Male British Family Annihilators, 1980-2012,” Howard Journal of Criminal Justice 53 (2014): 117-140.

[4] Shani D’Cruze, Sandra Walklate and Samantha Pegg, Murder: Social and Historical Approaches to Understanding Murder and Murderers (Cullompton: Willan Publishing, 2006); Pieter Spierenburg, A History of Murder: Personal Violence in Europe from the Middle Ages to the Present (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2008).

[5] Ania Wilczynski, Child Homicide (London: Greenwich Medical Media Ltd., 1997), 103-106; Carolyn A. Conley, Debauched, Desperate, Deranged: Women Who Killed, London 1674–1913 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), 206-210.

[6] The literature on newborn child murder / infanticide is extensive. Recent book-length studies include: Elaine Farrell, “A most diabolical deed”: Infanticide and Irish Society, 1850-1900 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013); Anne-Marie Kilday, A History of Infanticide in Britain c. 1600 to the Present (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

[7] Yardley et al, “A Taxonomy of Male British Family Annihilators,” 137. This work is based on 59 cases involving male perpetrators, but there were 12 cases of female-perpetrated family annihilation in the same period. The categories identified include: anomic (fear of poverty and loss of status); disappointed (believes that his family has let him down); paranoid (to protect the family from a real or imagined external threat); self-righteous (to blame and punish a partner or former partner).

[8] Katherine D. Watson, “Poisoning Crimes and Forensic Toxicology Since the 18th Century,” Academic Forensic Pathology 10 (2020): 37-40.

[9] Martin J. Wiener, Men of Blood: Violence, Manliness, and Criminal Justice in Victorian England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004); Judith Dorothea Rowbotham, “Gendering Protest: Delineating the Boundaries of Acceptable Everyday Violence in Nineteenth-Century Britain,” European Review of History—Revue européenne d’histoire 20 (2013): 945-966.

[10] Jade Shepherd, “‘One of the best fathers until he went out of his mind’: Paternal Child-Murder, 1864–1900,” Journal of Victorian Culture 18 (2013): 19.

[11] Ibid., 14.

[12] Smith, who was desperately poor, became the last woman executed in Britain for the murder of her own infant. She was a serial poisoner who confessed to killing seven other babies: Katherine D. Watson, “Religion, Community and the Infanticidal Mother: Evidence from 1840s Rural Wiltshire,” Family and Community History 11 (2008): 116-33.

[13] These figures come from the database which provides the evidence for: Katherine Watson, Poisoned Lives: English Poisoners and their Victims (London and New York: Hambledon and London, 2004).

[14] Richard Davenport-Hines, “Maybrick [née Chandler], Florence Elizabeth (1862–1941), convicted poisoner,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 Sep. 2004; accessed 22 Jun. 2023. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-54557.

[15] Jack Doughty, Come at Once – Annie is Dying (Stockport: Pentaman Press, 1987).

[16] Evening News (London), 21 August 1889, 4.

[17] Hilary Marland, Dangerous Motherhood: Insanity and Childbirth in Victorian Britain (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 6.

[18] Ania Wilczynski, “Mad or Bad? Child-Killers, Gender and the Courts,” British Journal of Criminology 37 (1997): 419.