Posted by Krista J. Kesselring, 31 October 2023.

While navigating the uncertainties and untruths that swirled in the wake of the Gunpowder Plot, King James’s councillors encountered a plotter of a different sort: Ralph Whitehand, a conjuror, or perhaps just a counterfeiter and a crook. Twelve privy councillors and high court justices assembled in the Court of Star Chamber in Westminster Palace on 22 November 1605. There, they heard that Whitehand had made a girdle of human skin to wear while professing to command the spirits. The prosecutor showed spectators the books and painted scroll Whitehand used in his alleged conjurations. And despite Whitehand’s early assertions of innocence, he ultimately confessed — boasted, perhaps — that he could even turn the rushes that covered the floor into spirits and serpents. Aghast, the judges sentenced him to ‘the greatest punishment they could’, according to one observer’s report: as Star Chamber wasn’t a regular court of common law, they couldn’t impose sentence of death, so this meant the pillory, loss of his ears, and perpetual imprisonment.[1]

Whitehand was perhaps lucky in one sense: just the year before, Parliament had enacted a new law that heightened penalties for conjuration and witchcraft, making any use of the dead or invocation of evil spirits for witchcraft, sorcery, charms, or enchantment a crime punishable with death, if tried in the common law courts.[2] But he was deeply unlucky in having come to the attention of Attorney General Edward Coke for his part in another crime altogether, and at a time when the authorities were showing increasing interest in deriding claims to possession, witchcraft, and sorcery as fraudulent. As such, one wonders if Whitehand’s confession constituted not a victory but something of a set back for Coke and the king’s councillors.

Coke had started proceedings against Whitehand as an accessory in a case of counterfeiting and defamation focused on William and John Clibbury. The Clibburys had engaged in a fairly routine riotous property dispute in Essex which led to William’s imprisonment in 1602. Brother John then went to London and approached Whitehand, an acquaintance from university, who had a reputation as a master forger and ‘counterfeiter of the handwriting of diverse honorable persons’.[3] John wanted to bring the Justices of the Peace who’d imprisoned William into disrepute to help secure his brother’s release, so he asked Whitehand to forge letters first from Sir John Fortescue and then Sir Robert Cecil – Queen Elizabeth’s Chancellor of the Exchequer and her principal secretary, respectively – that denounced the local JPs and ordered the visiting assize court judges to remove them from the bench. When William died in gaol, John’s resolve for revenge strengthened. But, in the end, the assize judge who received the letters recognized them as counterfeits. Sir Thomas Gardener, one of the JPs maligned in the forged missives, seems to have brought John Clibbury to the Attorney General’s notice. Coke filed his charges against the men in Star Chamber, an ‘extraordinary’ court with a special remit to deal with frauds and deceits in derogation of justice.

Coke entered a bill in February of 1605 which noted at its end that Whitehand wasn’t just a forger, but also a conman who claimed a great skill in conjuring and an ability to find lost and stolen goods. In Coke’s telling, the problem wasn’t magic but deceit, and the things Whitehand did to convince his marks that he was highly skilled in his craft: Whitehand claimed that to call upon the spirits he first had to baptize a dog and consecrate it to the devil, which he had done ‘to delude simple, ignorant people the more’. He had also, troublingly, ‘caused to be digged up the dead corpse of a Christian creature and most inhumanely caused the dead body to be flayed, and within the skin thereof did attempt diverse wicked and unlawful acts’.[4]

It was quite the addendum to the bill of complaint. And when John Clibbury died of plague, Coke’s attentions focused more intently on Whitehand. Whitehand had been charged with theft in another matter; the constables who searched his lodgings found books and a scroll rich with magical lore. Whitehand initially responded to Coke’s allegations by insisting that he had done nothing other than by the ‘Rule of Astronomy and Astrology, which he thinketh to be lawful for any scholar to practice’. He denied profaning baptism or flaying corpses.

Over the coming months, at least thirteen people were called in to depose about Whitehand’s life and actions. Whitehand sought to depict the witnesses who testified against him as having been bribed – aside from the more prosaic payments, he said that Gardener had promised one man a license to ‘draw beer and keep a taphouse in Halstead’. He tried to malign the credit of another hostile deponent, Jane Stafford, by noting that she had borne bastards to two different men and was so poor that when her first infant died, she had to beg for the fees for burial. Since then, he said, she worked as a bawd in the Minories, a notorious den of debtors and petty criminals. He even claimed that she had crept into gentlemen’s beds against their wills. One of the men deposing against him lived from the proceeds of his wife’s sex work, Whitehand alleged. Finally, he maintained that John Clibbury had cleared him of involvement in forging the letters on his deathbed.

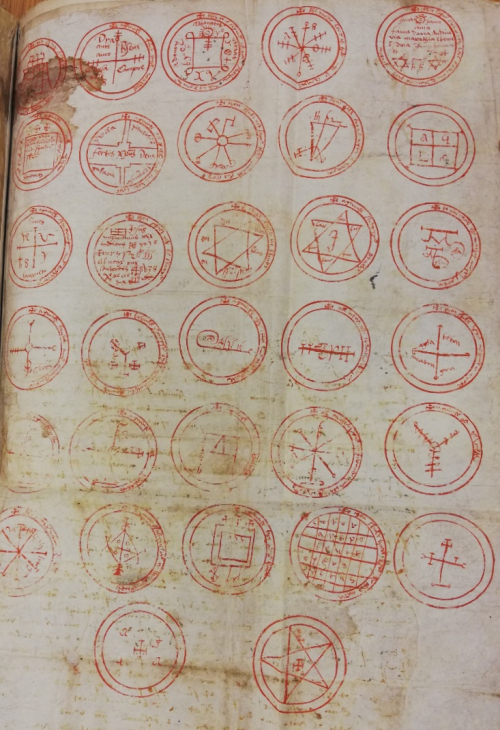

But Coke seemed persuaded by the evidence against Whitehand. Witnesses cast doubt on the deathbed story and said they had heard Clibbury bewail ever having turned to the forger. Some elaborated on Whitehand’s side hustle in using claims of conjuring to cheat the credulous: one deponent said he had heard Whitehand boast of having tricked a young gentleman by saying that he could put a spirit into his sword so that ‘all men should fly from him upon occasion’. Whitehand had taken the man into a field, demanded his ring as a sacrifice to the devil, and then told him to look away from the conjuring circle. An accomplice nabbed the ring once the mark turned his back. Jane Stafford testified that she didn’t know if Whitehand really could conjure spirits, but she had known him to cheat many people ‘under the colour of conjuring’. And then there was the physical evidence of the books and the illustrated scroll, which several deponents affirmed having seen Whitehand brandish as his bona fides.

By November, Coke felt he had his evidence marshalled and thus came the dramatic denouement in Star Chamber with Whitehand’s confession – or threat. Did Whitehand actually think himself to be a skilled practitioner of the magical arts, whether natural or demonic? Or was he simply a conman? At minimum, his story highlights the ubiquity of ‘service magic’, which ranged from the learned lore of scholars to the craft practices of cunning men and women, all available for a fee to those able and willing to pay.[5] The market for magical services was such that the unscrupulous could well make a living off the unwary.

Whitehand’s story also suggests the tensions in a transitional moment in the authorities’ responses to magic in its many forms. Prophecy, divination, and various magical practices that people used to see or to shape the future had long prompted very real concern from the authorities for their all-too-tangible effects in sustaining political opposition. Queen Elizabeth had famously turned to the ‘arch-conjuror’ John Dee to protect her from sorcerers’ threats.[6] Her 1563 Witchcraft Act passed in response to Catholic plotting; the Sedition Act of 1581 included sanctions for prophesying, witchcraft, and conjuration that threatened the Crown.[7] But even as Parliament was passing its new, tighter law against witchcraft and conjuration in 1604, the authorities were also trying to undermine such practices and beliefs by imputing cases to illness or imposture. Highlighting frauds and fakes became the order of the day. As bishop of London then archbishop of Canterbury, Richard Bancroft waged a campaign to discredit exorcisms, which both Catholics and puritans had used to attract support. New church canons issued in 1604 barred ministers from participating in exorcisms without special license, warning that they risked ‘imputation of imposture or cozenage’.[8] Concurrent with Whitehand’s case was the investigation into the claims of Anne Gunter, a young woman who feigned demonic possession to support accusations of witchcraft against two other women. King James himself interviewed Gunter and by October of 1605 was convinced that she was a fraud. Coke began a very public case against her and her father in Star Chamber just weeks after Whitehand’s hearing — a case that would end with a neater, tidier resolution than his.[9] Unmasking counterfeit conjurors might be a useful way to undermine the temptation to resort to magical means to take down political opponents or personal foes — if one was confident that they couldn’t actually turn the floor beneath one’s feet into a writhing mess of snakes and spirits. Writers on witchcraft often promised that the divinity of duly constituted justice kept its agents safe from magical harm, but perhaps it was best not to test that theory, at least not in Star Chamber.

***

To close on a different note: the talk of dogs consecrated to the devil and girdles crafted from corpses can distract a reader from the scheme and skills that first brought Whitehand to Coke’s notice. The plan to spring William Clibbury from gaol by wrecking the JPs’ reputations relied not on conjuring spirits but on counterfeiting handwriting. Whatever his skills as a sorcerer, one power Whitehand certainly did have was proficiency with the pen. Several of the deponents, including two of the three women, could not even write so well as to sign their names to their depositions, leaving only rough marks.[10] But Whitehand was an adept. The assize judge recognized the letters as counterfeits not because of the writing but the content and context, thinking them unusual requests to receive from the purported senders. Coke himself noted how very like the original hands the forgeries looked. As we navigate our way through our new age of AI-augmented uncertainties and untruths — now including the products of algorithms that can not just read but even replicate handwriting — the ease with which occult knowledge and arcane skills can foster frauds and fakes may well be the spookier resonance of Whitehand’s tale today.

Images:

Feature image: From Christoper Marlowe, The tragicall history of the life and death of Doctor Faustus (1631), courtesy of The British Library.

The magical seals come from a late 16th century–early 17th century text: British Library, Add MS 36674, f. 111r, courtesy of The British Library.

The detail of an amulet roll (15th century), comes from British Library, Harley Roll T 11, courtesy of The British Library.

The ‘handwriting’ image comes from Calligrapher.ai, but see also the UCL project that allows the replication of specific historical hands.

Notes:

[1] For the judgement: John Hawarde, Les Reports del Cases in Camera Stellata 1593 to 1609, ed. William Paley Baildon (London 1894), pp. 250-1. For the proceedings, see the files at The National Archives (Kew) [TNA], esp. STAC 8/9/1 but also STAC 5/A44/14, STAC 5/A47/36, and STAC 7/1/5. My thanks to Jessica Becker for photographing the final three files, which include additional allegations of forgery and counterfeiting, e.g., of the seal of the Ecclesiastical Court of High Commission.

[2] 1 Jac. I, c. 12, An Acte against Conjuration, Witchcrafte, and dealing with evill and wicked Spirits (1604).

[3] TNA, STAC 8/9/1. Further hints of the Clibburys’ prior encounters with the courts can be gleaned from the Essex Record Office catalogue.

[4] TNA, STAC 8/9/1, the source of all quotations here unless otherwise indicated. The language about the ‘Christian creature’ echoes the talk of using a ‘Christian body’ in a much earlier case of spirit-assisted treasure hunting previously discussed by Tom Johnson on this blog, in ‘Christened Cockerels and Heretical Hill-Diggers: Treasure Trove in Medieval England’.

[5] See, e.g., Owen Davies, Cunning-folk: Popular Magic in English History (London, 2003); Tabitha Stanmore, Love Spells and Lost Treasure: Service Magic in England from the Later Middle Ages to the Early Modern Era (Cambridge, 2022); and Taylor Aucoin, ‘The Magiconomy of Early Modern England‘, Forms of Labour blog, 4 November 2020. See also Owen Davies, Grimoires: A History of Magic Books (Oxford, 2009), on the ‘democratization’ of learned magic in the age of print and the efforts to control this spread.

[6] Glyn Parry, The Arch Conjuror of England: John Dee (New Haven, 2012). On the political aspects of magical practices see also, e.g., Peter Elmer, Witchcraft, Witch-Hunting, and Politics in Early Modern England (Oxford, 2016); Francis Young, Magic as a Political Crime in Medieval and Early Modern England: A History of Sorcery and Treason (London, 2018); Alexandra Walsham, “’Frantick Hacket’: Prophecy, Sorcery, Insanity, and the Elizabethan Puritan Movement’, Historical Journal 41.1 (1998), 27-66 and Walsham, ‘The Holy Maid of Wales: Visions, Imposture, and Catholicism in Elizabethan Britain’, English Historical Review 132, no. 555 (2017), 250-85.

[7] 5 Eliz 1, c. 16 and 23 Eliz, c. 2. Norman L. Jones, ‘Defining Superstitions: Treasonous Catholics and the Act against Witchcraft, 1563’, in State, Sovereigns, and Society in Early Modern England, ed. Charles Carlton, et al. (Stroud, 1998), pp. 187-203 and Michael Devine, ‘Treasonous Catholic Magic and the 1563 Witchcraft Legislation: The English State’s Response to Catholic Conjuring in the Early Years of Elizabeth I’s Reign’, in Supernatural and Secular Power in Early Modern England, ed. Michael Harmes and Victoria Bladen (London, 2015), pp. 67-94.

[8] Philip C. Almond, Demonic Possession and Exorcism in Early Modern England: Contemporary Texts and their Cultural Contexts (Cambridge, 2004), quote at 290; see also Michael Macdonald, ed. Witchcraft and Hysteria in Elizabethan London: Edward Jorden and the Mary Glover Case (London, 1991).

[9] Brian P. Levack writes about both the Gunter case and King James’s increasing interest in refuting fraudulent claims of possession, etc., in ‘Possession, Witchcraft, and the Law in Jacobean England’, Washington and Lee Law Review 52.5 (1996), 1613-40. On the Gunter case, see also J.A. Sharpe, The Bewitching of Anne Gunter: A Horrible and True Story of Deception, Witchcraft, Murder, and the King of England (New York, 2000). For a later case of imposture revealed in Star Chamber, see Richard Raiswell, ‘Faking It: A Case of Counterfeit Possession in the Reign of James I’, Renaissance and Reformation, 23.3 (1999), 29-48. Young, Political Crime, 167-70, also provides a brief overview of another case brought to Star Chamber, centered on Sir Thomas Lake and launched in 1620, which included allegations about a man who tried to ‘infatuate the king’s judgement by sorcery’. That Coke specifically retained an interest in exposing fraudulent sorcerers even after becoming Chief Justice is suggested by a letter he sent the king in February of 1616, noting that he’d rounded up thirteen ‘imposters or wizards pretending to tell fortunes, to procure love, to alter affections, to bring again stolen goods’ (etc.), all in the midst of the Somerset trial, in which allegations of sorcery also arose and produced a dramatic scene in the Court of King’s Bench when the production of the magic books coincided with a loud crack that made spectators fear the devil’s appearance among them: TNA, SP 14/86, fo. 89d, Alistair Bellany, The Politics of Court Scandal in Early Modern England: News Culture and the Overbury Affair, 1603-1666 (Cambridge, 2002), 150-1.

[10] On the significance of marks v. signatures, and their use as an indicator of a hierarchy of reading abilities and competencies with the pen, see Mark Hailwood, ‘Rethinking Literacy in Rural England, 1550-1700’, Past and Present 260.1 (2023), 38-70.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Great to see this. I have been researching Whitehand through a family history link, and I see there is more to find He was involved in 3 Star Chamber cases, the final one initiated by himself. He latterly described himself as a gentleman impoverished by imprisonment.

LikeLike

Interesting! I’ll be curious to see more details about Whitehand and his career. The fines list suggests that he did pay a substantial fine and indicates that he was in the Fleet prison (E 159/432 m. 128): http://aalt.law.uh.edu/J1/E159no432/aE159no432fronts/IMG_7744.htm

LikeLike

A brief account of Ralph Whitehand is in my blog https://www.exploringsurreyspast.org.uk/catch-him-if-you-can-or-on-the-tail-of-my-wicked-ancestor/. I can see a £1k fine might be rather disabling! Thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person