By Cassie Watson; posted 19 December 2023.

The history of serial poisoning shows that it seemed to attract two types of killer, broadly speaking: those who found poisoning to be an effective means of achieving personal aims, often financial;[1] and those whose motives were more difficult to understand and, in many cases, remained uncertain.[2] A previous post examined early modern British poisoners who fall into the first, and largest, grouping. This post considers three examples of the latter, much smaller category. Although this group is now populated mostly by healthcare serial poisoners,[3] its earlier inhabitants provide a revealing overview of the evolution of concepts related to the psychology of crime.

A Phrenological Defence: Hélène Jégado, 1852

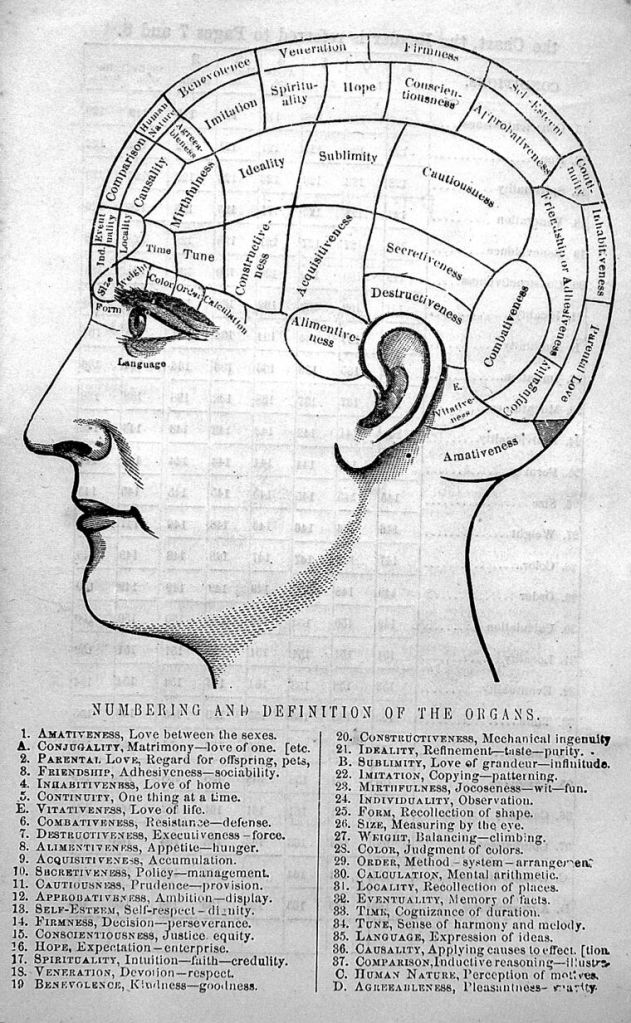

Given the scale of her crimes, both proven and alleged, it is somewhat surprising that the trial and execution of French serial poisoner Hélène Jégado (1803–1852) received so little attention in the British press. Following her condemnation at the Court of Assizes of Ile-et-Vilaine, in Rennes, several newspapers reprinted the account published in Galignani’s Messenger, but without any comment other than that hers was an extraordinary case, as “not less than 43 persons had been poisoned by her with arsenic.”[4] While all the reports noted that her defence appealed to the principles of phrenology, only the Liverpool Albion highlighted this in its headline, “A Wholesale Poisoner: A Phrenological Plea.”[5] With no moral or factual evidence that could explain her repeated acts of poisoning,

“The only defence set up for her was founded on phrenological principles. It was contended that the organs of hypocrisy and destructiveness were developed to a degree which overpowered the moral faculties, and that, although, it would be unsafe to leave her at large, she ought not to be condemned to capital punishment; the peculiarity of her organization rendering her rather an object of pity. The defence failed entirely, and the jury having delivered a verdict without extenuating circumstances, the court condemned her to death.”[6]

Over 80 years later, crime writer Victor MacClure (1887–1963) published an account of the case that reviews highlighted for its “exposition of criminal psychology,” particularly that of Hélène Jégado, “who for sheer love of witnessing suffering poisoned every family in which she took service as a maid, and was only discovered when she took to murder for spite.”[7] MacClure’s account, the review claimed, was “masterly and acute,” but it offered little depth in its assessment of Jégado. Her earlier crimes, perpetrated between 1833 and 1841, “were quite lacking in discoverable motive,” and so MacClure concluded that “She seems to have poisoned for the mere sake of poisoning.”[8] However, when Jégado moved to Rennes and began once again to poison those around her (1849–1851), the motive was said to be spite. MacClure was unable to explain why Jégado ceased her murderous activities for nearly a decade, said nothing about phrenology but referred explicitly to her hypocrisy, and thought it difficult to avoid the conclusion that she was mad.[9] A more recent assessment, citing a book published in 1970, ascribes her motive to jealousy of anyone who appeared to be “treated preferentially.”[10] Surely there was more to it than this?

Insanity and Inexplicable Crimes: Maria van der Linden, 1885

Another prolific Continental serial poisoner came to light in December 1883, when a 45-year-old mother of three, Maria van der Linden (1839-1915) of Leiden, was arrested on suspicion of having murdered 16 people in a relatively short period of time. Her motive was assumed to be money,[11] and it was eventually established that she had killed 27 people and harmed 45 others between 1869 and 1883. At her trial in April 1885, some of these murders were found to have offered no financial benefit, so that a question about her sanity arose: “it is not surprising, therefore, that her counsel has set up the plea that she is subject to a monomania for poisoning.”[12] Three eminent doctors examined her mental state and found her to be entirely sane, upon which her lawyer claimed that she suffered from moral insanity.[13] All observers agreed that whether she was a “murderous monomaniac or a wretch devoid of all moral sense,” the case was undoubtedly unique.[14]

In seeking to identify a reason for this woman’s apparently longstanding habit of poisoning those around her, at least three possibilities were raised: monomania (a form of partial insanity) and moral insanity (an early conceptualisation of personality disorder), both concepts developed in the first half of the nineteenth century but largely abandoned by the 1850s; and homicidal mania, a disease entity underpinned by the notion of delusional insanity.[15] All of these medico-legal theories were attempts to explain otherwise inexplicable crimes, by positing a type of insanity that affected the will rather than the intellect.[16] None was particularly convincing to lawyers, judges and juries asked to consider a calculating serial poisoner, yet the suspicion remained that such criminals could not be wholly sane. In an oblique reference to England’s McNaughtan Rules, a turning point in the history of the insanity plea,[17] the Western Daily Press noted that van der Linden’s criminality “is so excessive as to make it difficult to believe that the woman can possibly be of perfectly sound mind, although it is likely enough that she has known that murder is wicked.”[18] But unlike McNaughtan, who was sent to the criminal wing of Bethlem Hospital,[19] van der Linden was sentenced to penal servitude for life.[20]

The Sadistic Killer: Graham Young, 1972

A new possibility for explaining serial homicide was raised by the case of the German serial sex killer Peter Kürten (1883–1931), whose interviews with psychiatrist Dr Karl Berg in 1930 and 1931 formed the basis of Berg’s book, The Sadist, published in 1938.[21] Berg concluded that Kürten was a sadistic psychopath, a practised liar and deceiver whose excessive vanity and ego enabled him to justify a long criminal career on the grounds that he was taking vengeance on a society that had treated him unjustly.[22] This sort of explanation might apply, at least to some extent, to Hélène Jégado. But it was a male British serial poisoner who became known as a sadistic killer: Graham Young (1947-1990), the so-called Teacup Poisoner.

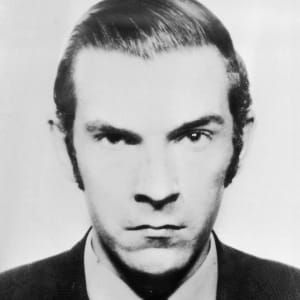

Young was unusual in that his earliest crimes were committed in childhood: he was obsessed with poisons and began to administer doses of antimony to family and friends, culminating in the death of his stepmother from a single dose of thallium in April 1962. According to Paul Bowden, a forensic psychiatrist, Young “took a particular interest in titrating doses of poison with specific symptoms and signs, and in choosing who should live and who should die. Later he was to say that he liked the sight and sound of pain.”[23] Whilst on remand Young admitted that “using the poisons gave him a sense of power, and after his arrest said that he was missing the power they gave him.”[24] This was a sentiment that Jégado and van der Linden might well have recognised, and Young’s personality traits certainly fit many of those identified in Dr Robert Brittain’s classic paper, “The Sadistic Murderer.”[25] Young pleaded guilty to three charges of administering poison with intent to cause grievous bodily harm (he was never charged with his stepmother’s murder, which he confessed to years later), and, diagnosed with a psychopathic disorder, sentenced to 15 years in Broadmoor Hospital.

had been angry with the machine which he believed had cheated him.”

Young was discharged from Broadmoor in February 1971. Although he hoped he was cured of his addiction to poisoning, a brief reminder of his schoolboy haunts was all it took to reignite the passion.[26] By the end of November he had been arrested and charged with two murders and two attempted murders: he had put thallium in the tea and coffee served to his new work colleagues, and his diary revealed the sense of power he felt as he first experimented upon and then decided to kill his victims.[27] He was sentenced to life imprisonment and, despite a later diagnosis of schizophrenia, remained in prison until his death.

Conclusion

Jégado, van der Linden and Young were uncommon criminals by any standard, but whether the mysterious something that drew them to the repeated use of poison was similar or not can only be a matter of conjecture. They all seem to have enjoyed the sense of power that poisoning gave them, but this was by no means unique to poisoners: it was recognised as a feature of other types of serial homicide in the 1930s.[28] However, the medico-legal understanding of serial perpetrators has been refined over time, and it now seems plausible to suppose that these three individuals were sadistic killers, suffering from a personality disorder rather than mental illness. Modern assessments of ‘dark’ personality traits acknowledge a link between sadism and psychopathy,[29] but note that while sexual sadism is a recognised disorder, its non-sexual counterpart is not considered a distinct entity within itself and requires further investigation.[30] The history of serial poisoning offers one way in which to approach this aim.

Images

Main image: Death as a lethal confectioner making up sweets using arsenic and plaster of Paris as ingredients; representing the toxic adulteration of sweets in the 1858 Bradford sweets poisoning. Wood engraving after J. Leech, 1858. Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

Hélène Jégado (1803-1852), French serial killer, circa 1852. [Français: Gravure représentant l’empoisonneuse Hélène Jégado encadrée par deux gendarmes (Épinal, imprimerie Pellerin, vers 1852). Museum of Brittany; public domain.

New illustrated self-instructor in phrenology and physiology: with over one hundred engravings, together with the chart and character of / by O.S. and L.N. Fowler, 1859. Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

Photograph of Graham Young: taken by Young himself in a photo booth at Waterloo Station, circa 1971. Wikipedia.

References

[1] Katherine Watson, Poisoned Lives: English Poisoners and their Victims (London: Hambledon and London, 2004), chapter 5; Victoria M. Nagy, Nineteenth-Century Female Poisoners: Three English Women Who Used Arsenic to Kill (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), chapter 5.

[2] Michael Farrell, Criminology of Serial Poisoners (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), chapter 2; Michael Farrell, Criminology of Homicidal Poisoning: Offenders, Victims and Detection (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2017), chapter 7.

[3] Farrell, Criminology of Serial Poisoners, 77; Eric W. Hickey, Serial Murderers and Their Victims, 4th edn (London: Thomson Wadsworth, 2006), 257-258.

[4] See, for example, The Morning Advertiser, 20 December 1851, 3 and The Morning Post, 19 December 1851, 5. This estimate is too high: modern accounts suggest that she committed around 30 murders. See, for example, John Emsley, The Elements of Murder: A History of Poison (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 151-154.

[5] Liverpool Albion, 22 December 1851, 3.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Monsters in Female Form,” Reynolds’s Newspaper, 24 March 1935, 19.

[8] Victor MacClure, She Stands Accused (London: George G. Harrap, 1935), 158.

[9] Ibid., 182.

[10] Farrell, Criminology of Serial Poisoners, 84, 160.

[11] St James’s Gazette, 26 December 1883, 10. Similar reports appeared in dozens of English newspapers.

[12] Western Daily Press, 27 April 1885, 5.

[13] Banbury Advertiser, 30 April 1885, 7.

[14] Chester Courant, 29 April 1885, 3.

[15] Joel Peter Eigen, Witnessing Insanity: Madness and Mad-Doctors in the English Court (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1995), chapter 3; Joel Peter Eigen, “Diagnosing Homicidal Mania: Forensic Psychiatry and the Purposeless Murder,” Medical History 54 (2010): 433-456.

[16] Janet Colaizzi, Homicidal Insanity, 1800–1985 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press 1989).

[17] Richard Moran, Knowing Right From Wrong: The Insanity Defense of Daniel McNaughtan (New York: The Free Press, 1981).

[18] Western Daily Press, 27 April 1885, 5.

[19] Moran, Knowing Right From Wrong, 116.

[20] Gloucestershire Chronicle, 9 May 1885, 6.

[21] Karl Berg, The Sadist, trans. Olga Illner and George Godwin (London: The Acorn Press, 1938).

[22] Ibid., 141-156.

[23] Paul Bowden, “Graham Young (1947–90); the St Albans Poisoner: His Life and Times,” Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health 6, no. S1 (1996): 18.

[24] Manchester Evening News, 5 July 1962, 7.

[25] Robert P. Brittain, “The Sadistic Murderer,” Medicine, Science and the Law 10, no. 4 (1970): 198-207.

[26] Bowden, “Graham Young,” 20.

[27] The Scotsman, 30 June 1972, 11.

[28] MacClure, She Stands Accused, 36-37. The word sadism is not used in this book.

[29] Debra O’Connell and David K. Marcus, “A Meta-analysis of the Association between Psychopathy and Sadism in Forensic Samples,” Aggression and Violent Behavior 46 (2019): 109-115.

[30] Lucy Foulkes, “Sadism: Review of an Elusive Construct,” Personality and Individual Differences 151 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.07.010.