By Cassie Watson; posted 25 March 2024.

The recent chemical attack in London bears all the tragic hallmarks of its Victorian forerunners:[1] the crime was planned in advance; the victim and perpetrator were known to one another; the probable motive was the breakdown of their relationship; the victim has lost an eye; and the perpetrator was also seriously injured in the assault. However, this crime differs from classic cases of vitriol throwing in one significant manner: the perpetrator was eventually found dead, believed to have committed suicide.[2]

This is extremely unusual in comparison to nineteenth- and twentieth-century cases of assaults involving corrosive fluids, and prompted me to take another look at the dataset of historic cases I compiled for a recent project. In over 500 acid attacks, two of the perpetrators took their own lives immediately or soon after the assault,[3] while a third committed suicide in prison following his conviction.[4] One victim, a young man who had been blinded in one eye in 1888, killed himself in despondency after losing a civil suit for damages.[5] However, a careful search revealed a somewhat more extensive history of suicide threats and attempts among acid throwers. While still a very small number in relation to the greater propensity of murderers to kill themselves,[6] this small group nonetheless offers some further insights into the range of emotions that underpinned this relatively rare but extremely vicious form of assault.

Acid Assault and Threats of Suicide

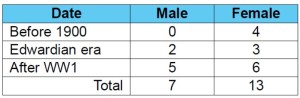

A total of 20 cases (3.9%) involved declarations, by an acid thrower after they had attacked their victim, that in some way referred to suicidal feelings or attempted suicide. While his underlying motive may have been similar, this figure excludes one man who deliberately injured his own face with acid after assaulting four people in 1968, and was detained under the Mental Health Act 1959.[7] The distribution of the cases by date and gender is summarised in the table below.

Four perpetrators, two men and two women, claimed that they had bought acid with the intention of committing suicide. In effect, they sought to offer an explanation that might mitigate their apparently premeditated act, by construing it as an accident or due to a sudden loss of control. For example, in 1906 William Woodard told police that he bought sulphuric acid intending to commit suicide if his wife did not return home that night. He tried to persuade her but had been rebuffed; when he saw her the next day, he lost his temper and threw it over her.[8] But one woman, whose husband had abandoned her and their four children for another woman, was unapologetic when charged, telling investigators: “You know that it wasn’t a sudden impulse it was fully premeditated. I feel sometimes like committing suicide but it is my four children, the boy has gone without boots and they have only dry bread for breakfast — that’s what Thomas has done for them.”[9] The victim was not her husband but his mistress, who suffered relatively slight damage from ammonia. Rose Anne Thomas’s sentence of twelve months imprisonment was reduced on appeal to three.[10] The court’s decision must have taken her suicidal depression into account, along with the fact that the victim had not been seriously injured.

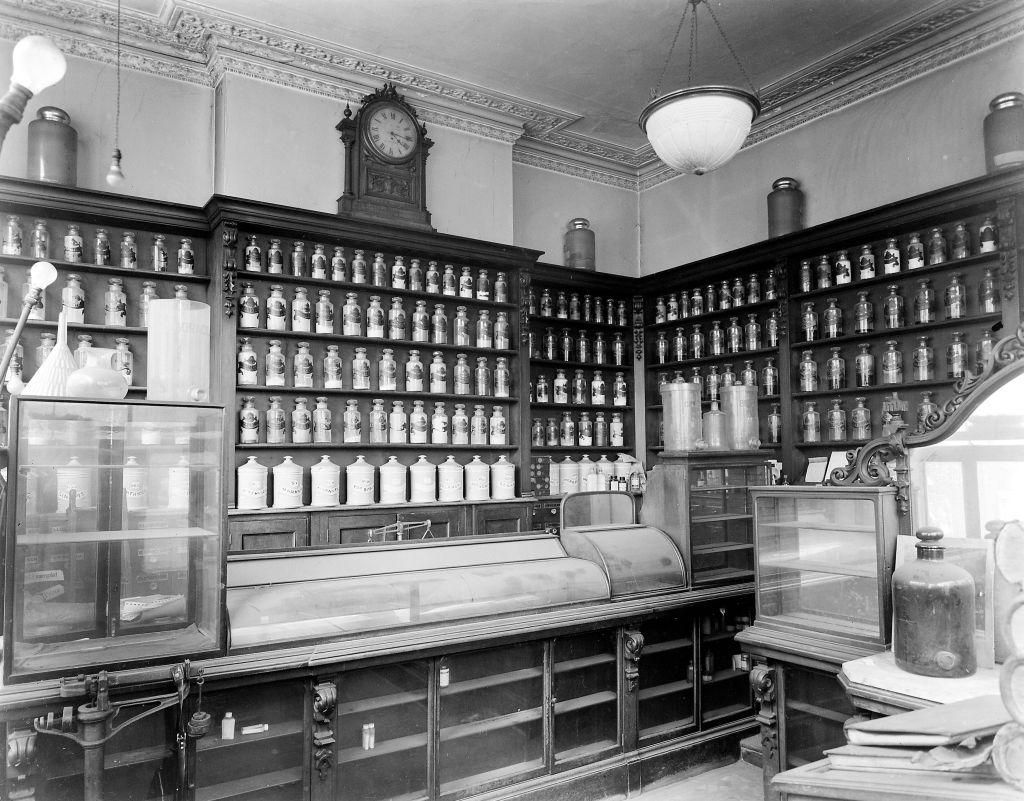

In one curious case in 1923 the question of suicide was raised by the victim, not the perpetrator. Two men had a series of increasingly violent confrontations after a dispute destroyed their friendship, culminating in an incident that took place in the perpetrator’s chemist shop. The victim, a butcher, goaded his former friend: “I will either make you shoot me, so that they will hang you like a dog, or make you commit suicide, or clear out of town.”[11] The chemist, John Mainprize, then rushed to the back of his shop, took a bottle containing some unnamed corrosive fluid from a shelf, and threw it, causing burns to the victim’s head and face. In court, the nature of the provocations that Mainprize had experienced evidently proved persuasive to the jury, who acquitted him.[12]

Acid Assault and Attempted Suicide

In fourteen of the twenty cases, the perpetrator actually attempted to commit suicide; in four instances the individual was charged with that crime as a second or third count on an indictment for throwing a corrosive fluid. Two features concerning these admittedly small numbers are worth noting. Firstly, ten of the acid throwers who subsequently attempted suicide were female, and only four were male; yet two of these men (50%) were charged with attempting suicide, compared to two of the women (20%). Secondly, the chronological distribution of these fourteen cases suggests a growing tendency for attackers to attempt suicide: four cases occurred prior to 1900 (1829-1888, all women), four during the Edwardian era (1904-1909, one man and three women), and six after 1910 (1924-1949; three men and three women).

These figures, and those included in Table 1 above, tally with conclusions reached by Olive Anderson nearly forty years ago. She found that “men increasingly became more prone to suicide than women,” particularly older men;[13] and that by the early twentieth century, those who committed suicide saw it as an escape from “depression, disappointment, and self-reproach.”[14] Similarly, Victor Bailey’s work on suicide in Victorian Hull has shown that disruptions to personal attachments, such as romantic disappointment or marital separation, were prominent factors in the decisions of older men and younger women to commit suicide.[15]

Acid throwers fit this profile. While one Scottish woman was clearly mentally ill,[16] the rest of the individuals in the sample had suffered some kind of relationship-related shock: they became jealous due to the appearance of a love rival, had been jilted or abandoned, discovered an affair, or had been wrongly accused of infidelity. While some of these individuals had previously attempted suicide — which suggests a history of conflict and, possibly, mental illness — most committed the act in a sudden reaction to a specific situation. As Arthur Dashwood, aged 69, noted in his statement to police after his arrest for throwing a corrosive fluid over his girlfriend, “I was very worried after I’d done this to Gracie and that was why I took the aspirin tablets on Tuesday.”[17] He later denied this was a suicide attempt (he took 120 tablets), but the medical officer at Brixton Prison found him to be depressed and confused. An old history of previous convictions for living on immoral earnings, assault on police, and the remarkably long-lived offence of being an incorrigible rogue,[18] probably contributed to his sentence of three years’ penal servitude.

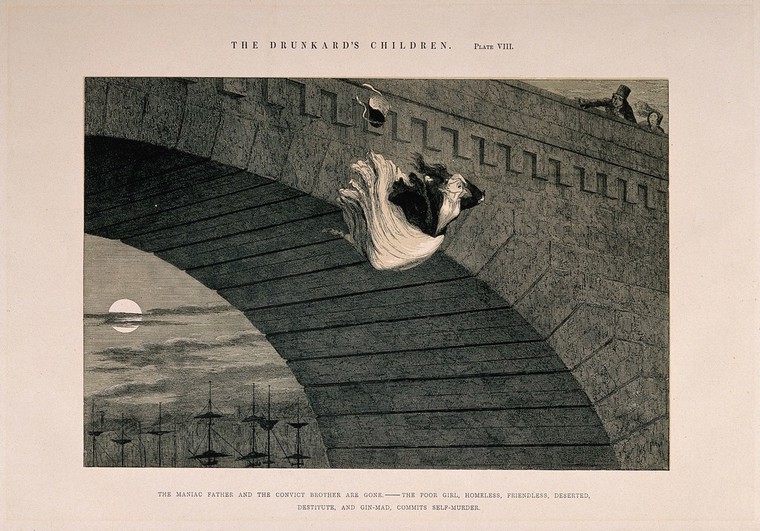

The women in this group were also sent to prison, though generally for much shorter periods of about a year. Only Ellen Smith, 32 and married, who was homeless as a result of being abandoned by the man she had been living with for three years, was sent to penal servitude. She had twice bought vitriol for the avowed purpose of blinding her ex-lover, but succeeded only in injuring a teenage boy who happened to be nearby. En route to the police station, she threw herself into the dock at Wapping, but was got out alive. The year was 1861 and although she was charged with both offences in the police court,[19] the indictment at the Old Bailey cited only the acid throwing.[20] Despite the fact that she was clearly guilty, a sentence of three years seems excessive in relation to many imposed at the time; her suicide attempt does not appear to have fostered any sympathy.

The same can be said of George Henry Horton, 49, who was sentenced to four years’ penal servitude at the Staffordshire autumn assizes in 1932. He was charged with throwing vitriol on his wife, who had left him, and with attempting to commit suicide. She had agreed to meet him in a pub, but tried to leave when Horton became more and more argumentative. He had obviously come prepared to harm her: he threw acid at her face, then poured more from the bottle over her before drinking from it.[21] He was found guilty of throwing vitriol, then pleaded guilty to a second charge of attempting to commit suicide and the judge passed sentence of one month’s imprisonment, the sentences to run concurrently.[22]

The fact that Mrs Horton had been blinded in one eye suggests why the judge passed a relatively long sentence, but there might have been a different outcome at another time or in another court. Just twelve years later, an acid thrower was sentenced to two years’ probation, though this more lenient reaction may have been related to the fact that he had used a far less dangerous substance. A corporal in the RAF, John Pollard threw acetic acid on the woman who broke off their engagement, before cutting his wrist.[23]

Conclusion

Most acid throwers were completely unrepentant, and very few threatened or attempted to commit suicide. While expressions of suicidal intent might have been calculated to play on the sympathies of a judge and jury,[24] the decision to carry out this type of assault might almost by definition exclude those who were so despondent that they contemplated suicide. Most of the actual attempts seem to have been largely impulsive acts. The fact that so few occurred before the First World War – earlier cases were reported even when the perpetrator had succeeded in killing themselves – suggests that something had changed by the 1920s. Assault remains an under-studied form of interpersonal violence, but its links to important wider contexts such as emergency medical care, gendered access to resources and equal opportunities, judicial and public attitudes, and the stresses related to life cycle, suggests why it ought to be the focus of more detailed historical study.

Images

Main image: A young man holding a dagger threatens to kill himself while a young lady sitting on a chair next to him smiles at him, not taking his threat seriously. Coloured lithograph by J. G. Scheffer, circa 1823. Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

Late 19th century Chemist’s shop formerly owned by N. F. Tyler. Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

A destitute girl throws herself from a bridge, her life ruined by alcoholism. Etching by G. Cruikshank, 1848. Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

References

[1] Katherine D. Watson, Acid Attacks in Britain, 1760–1975 (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023).

[2] The Guardian, 9 February 2024.

[3] “Dreadful Suicide,” Mayo Constitution, 13 December 1830, 1; “Stairway Drama: Vitriol and Razor Glasgow Tragedy,” Belfast News-Letter, 17 November 1926, 4.

[4] Stamford Mercury, 7 June 1722, 9. The perpetrator pleaded guilty and was sentenced to transportation.

[5] Watson, Acid Attacks in Britain, 32.

[6] Samuel Cameron, “Self-Execution, Capital Punishment, and the Economics of Murder: Analysis of U.K. Statistics Suggests that Suicide by Murder Suspects is Not Influenced by the Probability of Execution,” American Journal of Economics and Sociology 60 (2001): 881-890; Jo Barnes, “Murder Followed by Suicide in Australia, 1973–1992: A Research Note,” Journal of Sociology 36 (2000): 1-11.

[7] Watson, Acid Attacks in Britain, 103-104.

[8] Woolwich Gazette, 6 July 1906, 6.

[9] The National Archives (hereafter TNA), CRIM 1/1974 Rose Anne Thomas 1949, deposition of Det Inspector George Miller, 3 March 1949.

[10] Ibid., Court of Criminal Appeal, Notification of Result of Application to the Full Court, 4 May 1949.

[11] Sheffield Daily Telegraph, 13 October 1923, 7.

[12] TNA, HO 140/381, Calendar of Prisoners, Yorkshire Autumn Assizes 1923, 16. Accessed via Ancestry, 25 March 2024.

[13] Olive Anderson, Suicide in Victorian and Edwardian England (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), 418.

[14] Ibid., 420.

[15] Victor Bailey, ‘This Rash Act’: Suicide Across the Life Cycle in the Victorian City (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998), 253-255.

[16] Watson, Acid Attacks in Britain, 89-90.

[17] TNA, CRIM 1/1534 Arthur Dashwood 1943, statement of Arthur Dashwood, 9 June 1943.

[18] Ibid., Convictions recorded against Arthur Dashwood, March 1907 to March 1911. See the Vagrancy Act 1824, 5 Geo IV c.83 s.5.

[19] “Terrible Outrage by a Woman,” Bedfordshire Mercury, 16 November 1861, 7.

[20] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 9.0) November 1861. Trial of Ellen Smith (32) (t18611125-45) (accessed: 25th March 2024).

[21] “Alleged Vitriol Attack on Woman. Husband Sent For Trial,” Illustrated Police News, 20 October 1932, 4.

[22] Coventry Evening Telegraph, 15 November 1932, 6.

[23] Hampshire Telegraph, 25 February 1944, 5.

[24] Amy Milka, “‘Preferring Death’: Suicidal Criminals in Eighteenth-Century England,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 53 (2020): 685-705.