Posted by Krista J. Kesselring 23 April 2024.

A document in the State Paper archive invites readers to revisit the contested passage of the 1604 Witchcraft Act and prompts a fresh question about the main set of English laws against harmful magic: just what did the people who passed these statutes have in mind when they prohibited the use of witchcraft, charms, and sorcery ‘to the intent to provoke any person to unlawful love’?

The 1604 Act is often seen as having a special significance because it lasted longer and covered more ground than its two predecessors. An Act passed in 1542 had been the first to make ‘conjurations of spirits, witchcrafts, enchantments, or sorceries’ capital crimes punishable in the courts of common law rather than simply sins subject to the church courts alone. Enacted in the reign of King Henry VIII, this early measure seems to have been little enforced and was soon repealed. After a failed attempt to pass a new law against conjurors and witches at the outset of Queen Elizabeth’s reign, one of the queen’s parliaments did enact another in 1563. Proposed in part to counter Catholic plots against the queen, this Elizabethan Act soon enabled a spate of criminal trials and executions of people accused of harmful magic. Then, in 1604, within a year of the accession of King James VI of Scotland to England’s throne, the English parliament passed yet another measure, one that included a few new elements: entertaining evil spirits – familiarly known as ‘familiars’ – or using human corpses for necromantic rituals became capital offences, for example. The Act also increased the penalty for those who harmed but did not kill someone by means of witchcraft from imprisonment to death. Intended ‘for the better restraining of said offences and more severe punishing the same’, the 1604 Act remained the law of the land through to 1736.[1]

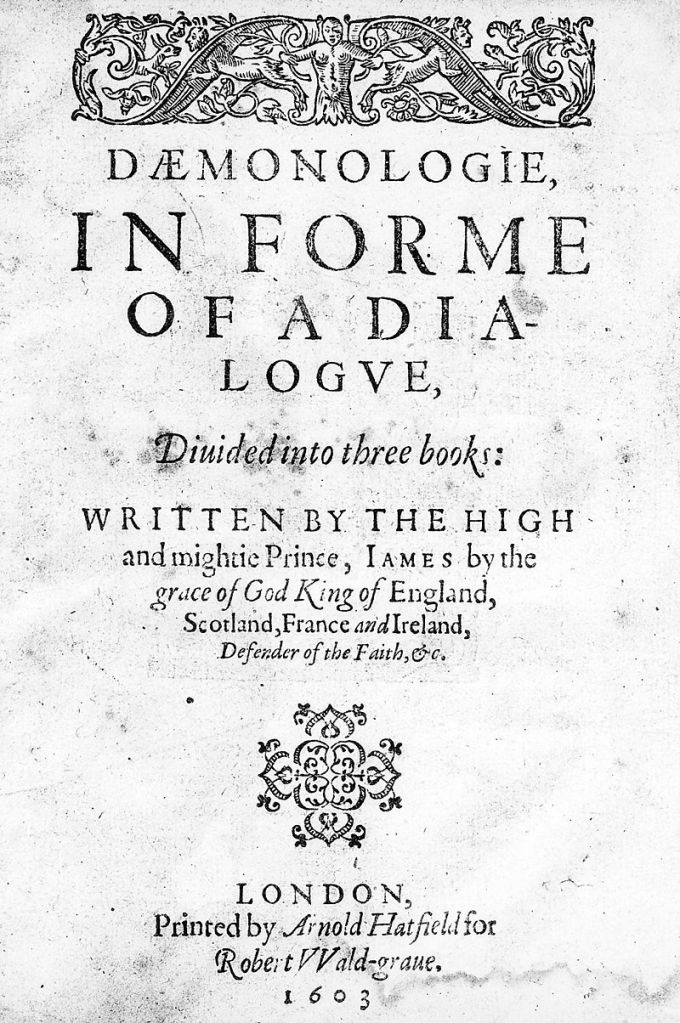

Given James of Scotland’s undoubted interest in witchcraft, it’s an easy but perhaps mistaken assumption that the king personally proposed the new, more stringent law with a wider scope.[2] James had (in)famously taken part in the trials of the North Berwick witches in 1590; he later authored the Daemonologie, a dissertation on the dangers of the magical arts first published in Scotland in 1597 and reissued in England upon his arrival in his southern kingdom. But as P.G. Maxwell-Stuart has persuasively argued, we have little reason to see James as the active agent behind the 1604 Act. The Act reflected neither the Scottish law against witchcraft nor the terms of James’s book.[3] Moreover, a long list of bills to consider proposing to the new parliament devised by members of the king’s council makes no mention of it: among measures to establish the new king’s estate, to reform the church and the courts, and to discipline ‘manners’—including bills against atheism, swearing, and duels—nothing like this Act appears.[4] James’s opening speeches to parliament say nothing of the subject. The king showed far more concern to secure parliamentary support for the union of his kingdoms and for Crown finances, the two subjects that dominated the first parliamentary session of his reign.[5]

Yet, the bill for a new law on conjuration and witchcraft was one of the very first items brought before the House of Lords, appearing on 27 March 1604, only its second day of business.[6] Who brought the bill forward and why? This parliament met in the wake of the Hampton Court conference, a debate between ‘puritans’ and bishops moderated by the new king, and alongside a Convocation of the clergy that was busily drafting new canons for the church, one of which sought to quell clerical involvement in exorcisms. Might the bill have emerged from discussions in these meetings? We have no clear answers, but attending to the Act’s legislative history—and not just the final text—might tell us a little something more about the pressures from which it emerged and help us better understand the significance of the law itself.

Certainly, the bill did not have a quick or straightforward journey. Two days after its introduction to the Lords, they sent it to a committee that included eleven bishops and men such as the ‘Wizard Earl’ of Northumberland. Committee members drew on the assistance of the attorney general and chief justices, the latter including Sir Edmund Anderson, a man who had previously expressed a need to hunt out witches more rigorously. (If not, he warned, ‘they will in short time overrun the whole land.’[7]) The committee deemed the initial bill ‘imperfect’ and introduced a new one on 2 April. The journal of the House of Lords notes without detail that further amendments were made, then read and approved on 7 May, with the text finally ‘engrossed’ – written up formally on parchment – and sent to the House of Commons on 11 May. There it received fresh debate. According to one scribe, ‘after long argument’, both for and against, the House rejected the bill.[8] The bill went back to committee, more amendments were made, and only when it was reintroduced did it finally pass the Commons on 7 June, though still with at least one member speaking against it. The Commons sent it back to the Lords on 9 June, where it was finally readied for the king’s assent.[9]

The journals of the Houses tell us nothing of the nature of the objections and amendments, but we can glean a few hints elsewhere. On the final, engrossed text of the bill preserved in the Parliamentary Archives we see edits denoting a few late changes. Some edits adjusted the date by which the Act would go into effect, pushing back the original, optimistic date of the ‘feast of Pentecost next coming’ – in 1604, that would have been 6 June, perhaps plausible for a bill introduced on 27 March but given the protracted debates, ultimately not viable. The final Act instead mandated Michaelmas, or 29 September. Whatever the date, specifying that the Act would go into effect within the time parliament was meeting was itself unusual. Typically Acts became effective upon the ending of a session. Other measures passed around the same time specified that they would go into effect one month, or forty days, or even two months after the end of the session. That the proposers of the bill for witchcraft inserted an earlier date suggests they felt a sense of urgency. Significantly, too, a line scratched out very late in the bill’s journey would have allowed capital penalties for anyone who ‘shall have any meeting or conventicle together with any witches, to or for the exercising of any witchcraft’.[10] Such an extension of penalties to people who met with witches for any witchcraft might well have allowed—or risked—entrapping people who turned to purveyors of magical services for fairly routine requests.[11] Someone had wanted an Act even more severe than what ultimately passed.

A note in the State Paper archive that seems to have been previously overlooked lists a few other amendments that were proposed along the way.[12] It included a proviso to ensure that peers of the realm would be tried by their fellow peers, a proviso that did appear in the final Act. But other suggested amendments did not, and one of them catches the eye: ‘put in these words, the detestable vice of buggery committed with mankind or beast’. Both the 1542 and the 1563 Acts, like the final text of the 1604 measure, made it a crime to use witchcraft, enchantment, or sorcery to provoke (or with the intent to provoke) any person to ‘unlawful love’. Whoever wrote this list of suggested amendments to the 1604 bill wanted to replace or to supplement the reference to ‘unlawful love’ with a rather more specific phrase about buggery.

Like witchcraft, ‘buggery committed with mankind or beast’ first became a capital crime in the reign of Henry VIII.[13] The word ‘buggery’ had long been associated with witchcraft and heresy and sometimes denoted ‘unnatural sex’ in general, even as it was coming to refer more often to sodomy specifically.[14] The assumption has long been that references in the witchcraft Acts to ‘unlawful love’ meant love magic, the use of potions, spells, and charms to induce anyone to love another.[15] But did the phrase perhaps mean something a bit different to legislators? Given the context of other events and Acts around the time of the 1542 statute’s creation, one wonders if ‘unlawful love’ meant actions such as adultery, incest, and buggery. After all, not long before, King Henry had reportedly complained that Anne Boleyn had used ‘sortileges and charms’ to have him marry her against his better judgement, a union described by one contemporary as ‘unlawful love’ for its incestuous qualities and ended upon accusations of her varied sexual offences.[16] Henry had gone on to marry Anne’s close kin, Catherine Howard, and then to have her executed on charges of treasonable adultery. Catherine’s attainder Act passed through the same session of parliament that produced the 1542 Witchcraft Act. In between the deaths of Anne and Catherine was the high profile execution of Sir Walter Hungerford in July 1540, found guilty of treason upon accusations that included magic, sodomy, and incest: he purportedly consulted a professional witch to predict the date of the king’s death and had sex with both male servants and his own daughter.[17] The Elizabethan witchcraft Act of 1563 passed alongside a law that revived the Henrician buggery Act, and indeed, one bill had initially dealt with both offences before being split. It’s been previously assumed that this was just an omnibus morals bill, but perhaps the connection was stronger than that implies.[18] This is all circumstantial at best, but it seems entirely possible that the references in the witchcraft Acts to ‘unlawful love’ didn’t mean just any love secured by magic but love deemed especially sinful or even criminal by the laws of the day. Either way, the line conveys a concern for the potential effects of magic on a person’s will or meaningful consent.

That someone tried (and failed) to add inducement to buggery to the 1604 Witchcraft Act is at least an interesting footnote to the histories of sexuality and witchcraft. Read alongside the original text of the Act, the proposal also reminds us that the laws themselves were products of disagreement and debate, with many authors and motives behind them, and created in specific contexts—even if their consequences lingered long after, shaping experiences and expectations in other times and places.

Images:

Feature image: Jan Steen, Bathsheba Receiving David’s Letter, c. 1659, via Wikimedia Commons.

Westminster from the river by Wenceslaus Hollar, c. 1647, via Wikimedia Commons.

Title page of King James’s Daemonologie, via Wikimedia Commons.

Image of a seventeenth-century parliament (from the trial of Stafford) by Wenceslaus Hollar, via Wikimedia Commons.

Clip from the original Act against Conjuration, Witchcraft, and Dealing with Evil and Wicked Spirits, Parliamentary Archives, London, Public Act, 1 James I, c. 12, HL/PO/PU/1/1603/1J1n12 (1604), © Parliamentary Archives, London; used with permission.

Clip from SP 14/8, f. 98, © The National Archives, Kew; used with permission.

Notes:

[1] James Sharpe, Instruments of Darkness: Witchcraft in England, 1550-1750 (London, 1996), pp. 88-93 offered a brief overview of this legislation. On the 1563 Act, see Norman Jones, “Defining Superstitions: Treasonous Catholics and the Act Against Witchcraft of 1563,” in State, Sovereigns and Society in Early Modern England, ed. Charles Carlton et al (Stroud, 1998), pp. 187-203 and Michael Devine, “Treasonous Catholic Magic and the 1563 Witchcraft Legislation: The English State’s Response to Catholic Conjuring in the Early Years of Elizabeth I’s Reign,” in Supernatural and Secular Power in Early Modern England, ed. Victoria Bladen and Marcus Harmes (Farnham, 2015), pp. 67-91. The three main English statutes in question are 33 Henry VIII, c. 8; 5 Elizabeth I, c. 16; and 1 James I, c. 12, available via the Statues of the Realm or, as linked above, The Statutes Project website. The Irish witchcraft Act of 1586 includes the same language of ‘unlawful love’ as will be discussed here.

[2] See, e.g., Wallace Notestein, A History of Witchcraft in England from 1558 to 1718 (Washington, 1911), pp. 101-105, and passing references in many more recent works.

[3] P.G. Maxwell-Stuart, ‘King James’s Experience of Witches, and the 1604 English Witchcraft Act’, in Witchcraft and the Act of 1604, ed. John Newton and Jo Bath (Leiden: Brill, 2008), pp. 39-46.

[4] The National Archives [hereafter TNA], SP 14/6, fos. 181-183, ‘Note of acts to be considered of against next Parliament.’

[5] See, e.g., Conrad Russell, King James VI and I and his English Parliaments, ed. Richard Cust and Andrew Thrush (Oxford, 2011, pp. 14-42 and ‘The Parliament of 1604-1610’, The History of Parliament: The House of Commons, 1604-1629, ed. Andrew Thrush and John P. Ferris (2010).

[6] It was, in fact, the first public measure to come before the Lords, with the few bills introduced the previous day all dealing with matters private to individual lords. See: ‘House of Lords Journal Volume 2: 27 March 1604’, in Journal of the House of Lords: Volume 2, 1578-1614, (London, 1767-1830), p. 267. British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/lords-jrnl/vol2/p267 [accessed 16 April 2024].

[7] Stephen Bradwell, ‘Mary Glovers Late Woeful Case, Together with Her Joyfull Deliverance’ (1603), in Michael Macdonald, ed., Witchcraft and Hysteria in Elizabethan London (London, 1991), p. 29.

[8] ‘House of Commons Journal Volume 1: 07 June 1604’, in Journal of the House of Commons: Volume 1, 1547-1629, (London, 1802), pp. 231-232. British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/commons-jrnl/vol1/pp231-232 [accessed 13 April 2024].

[9] For the journey through the Lords, see Journal of the House of Lords: Volume 2, 1578-1614, (London, 1767-1830), entries for 27, 29 March, 3 and 11 April, 7 and 8 May, 9 June; Journal of the House of Commons: Volume 1, 1547-1629, entries for 5, 7, 9 June, both first and second scribe (the latter entries are not paginated online).

[10] Parliamentary Archives, Public Act, 1 James I, c. 12, HL/PO/PU/1/1603/1J1n12 (1604), An Act against Conjuration, Witchcraft, and Dealing with Evil and Wicked Spirits.

[11] On such ‘service’ magic and its ubiquity, see, e.g., Owen Davies, Cunning-folk: Popular Magic in English History (London, 2003); Tabitha Stanmore, Love Spells and Lost Treasure: Service Magic in England from the Later Middle Ages to the Early Modern Era (Cambridge, 2022); and Taylor Aucoin, ‘The Magiconomy of Early Modern England‘, Forms of Labour blog, 4 November 2020.

[12] TNA, SP 14/8, f. 98, Notes of amendments to be made in the Act against Conjuration, Witchcraft, &c. [tentatively dated to 5 June 1604 by the Calendar of State Papers.] Maxwell-Stuart noted its brief description in the Calendar of State Papers, but seems not to have had access to the document itself, which makes clear that it was not, as he thought, a list of amendments proposed for the 1563 Act. It’s clearly referencing an earlier version of the 1604 Act. [Maxwell-Stuart, ‘The Act of 1604’, p. 39.]

[13] 25 Henry VIII, c. 6, An Act for the Punishment of the Vice of Buggery.

[14] On these connections, see e.g., Courtney Thomas, “’Not Having God Before his Eyes”: Bestiality in Early Modern England’, The Seventeenth Century, 26.1 (2011), 149-73 at 152-3; Alan Bray, Homosexuality in Renaissance England (New York, 1995), e.g., pp. 23-9; and H.G. Cocks, Visions of Sodom: Religion, Desire, and the End of the World in England, c. 1550-1850 (Chicago, 2017).

[15] See, e.g., Francis Young, Magic as a Political Crime in Medieval and Early Modern England: A History of Sorcery and Treason (London, 2018), p. 77 and Marion Gibson, ‘Applying the Act of 1604: Witches in Essex, Northamptonshire and Lancashire’, in Witchcraft and the Act of 1604, p. 118. On the longer history of love magic, see, e.g., Richard Kieckhefer, ‘Erotic Magic in Medieval Europe’, in Sex in the Middle Ages: A Book of Essays, ed. Joyce E. Salisbury (New York, 1991), 30-55.

[16] Young, Magic as a Political Crime, p. 71; TNA, SP 1/138, fo. 171; Retha Warnicke, The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn (Cambridge, 1989), pp. 191ff.

[17] Young, Magic as a Political Crime, pp. 74-6.

[18] 5 Elizabeth I, c. 17, An Act for the Punishment of the Vyce of Sodomye (1563.) See Jones, ‘Defining Superstitions’.