Posted by Sara M. Butler, 16 May 2024.

Depictions of the Middle Ages on television and in the movies often lead us to believe that medieval people were born, lived, and died all in the same village. This was simply not the case. Medieval people did travel. In fact, they had no choice but to travel. Even the best of farmers could not be entirely self-sufficient, so at the very least, they needed to journey to market towns to buy and sell produce and goods. The church’s stringent enforcement of prohibited degrees of kinship—no marriage within four degrees by blood (consanguinity), affinity, or sponsorship—meant that they also had to travel to find a spouse, because you usually had to go a couple of villages over to find someone to whom you were not too closely related. But most of all, people went on pilgrimage, to shrines both nearby and far off, in order to be healed, to have their sins forgiven, and to be inspired. Pilgrimage was a massive industry in late medieval Europe, advertised by miracle stories, souvenirs, even jingles. The constant flow of tourists brought in profits through offerings, but the residents of the towns housing those shrines also benefited through monies spent on food, shelter, and entertainment.

After the First Crusade (1096-1099), and the writing of travelogues that made people yearn to go to Jerusalem and walk in the footsteps of Christ, pilgrimage to the Holy Land became popular, and not just for the elite. Even Margery Kempe, a woman of middling rank from King’s Lynn in Norfolk, at the age of forty traveled to the Holy Land by herself. During her journey, she spent thirteen weeks in Venice, a hub for travelers. Between 1300 and the 1530s, Venetians became experts in “pilgrim trafficking,” that is, transporting pilgrims between Europe and the Levant. Ships embarked from Venice to Jerusalem twice a year. During this period, Venice was a waiting room of sorts, where pilgrims kept themselves busy until the next ship was set to sail.

The pilgrimage industry fundamentally altered daily life in Venice. By the end of the fifteenth century, Philippe de Commynes, the French ambassador, remarked that “most of the people [in Venice] are foreigners.”[1] Overrun with tourists, the city tried to capitalize upon the situation by promoting its own religious shrines, and providing organized city itineraries to entertain pilgrims awaiting their departure.[2] The potential for profit was recognized also by many foreign innkeepers and entrepreneurs who moved to Venice and set up shop, aware that pilgrims might prefer to stay at inns and conduct business dealings with those who spoke their native tongue. As a result, the city was “filled with whole colonies of foreign artisans and merchants pursuing their trades, some in constant rotation back and forth to their home country, and some in a state of almost permanent residency in Venice.”[3] Mini enclaves of different nations within Venice may have brought comfort to homesick travelers, but it also encouraged an unhealthy form of separate living, so that tourists had no need to learn the local customs and etiquette.

Having to compete with foreigners for business in their own hometown provoked a lot of tensions amongst Venetians. They particularly disliked the English, who they saw as a threat to Venetian commerce both in Italy and abroad. As a gauge of their resentment towards the English, Maria Fusaro highlights how the English were denied the reciprocal pact between polities that typically allowed foreigners use of summary procedure in the Venetian Giudici del Forestier (the court for foreigners). This pact was extended to most foreign nations living within Venice, so that their merchants could have commercial disputes resolved quickly. However, Venice refused to extend this privilege to the English until 1698.[4]

All of this sets the scene for what happened on 3 Mar. 1365, when simmering resentments and clashing cultures came to a head in an incident that led to the murder of English John, servant of Sir Henry Stromin, an English pilgrim in Venice awaiting embarkation.

The English pilgrim and his retinue were lodging at the Dragon Inn, situated behind the Doge’s Palace, close to the Ponte della Paglia, and on the site of the future Doge’s prison.[5] The inn was owned by John the Englishman (not to be confused with English John), one of those enterprising innkeepers who catered to an all-English crowd of pilgrims. On that day, around the hour of vespers, English John was with his fellow servant, Robin, in the stable behind the Dragon Inn, grooming their master’s horses, when a man unknown to them came into the stable and began urinating on the horse litter.

Appalled at what he perceived as simply bad manners, Robin scolded the newcomer and pointedly asked him to urinate elsewhere. The man replied, “thus would he do whether he liked it or not.” Exasperated by his response, John and Robin drove the man out of the stable, only to have him return moments later with a stone in hand that he pitched at John’s head, narrowly missing him. He then slapped Robin in the face. Robin asked, “Why strikest thou me?” to which the man responded, “Because it pleases me.” John grabbed the man by his beard, at which point the man drew a bread knife and stabbed John in his left side before fleeing. John collapsed to the ground. Accompanied by Jacky, his master’s companion, Robin pursued the perpetrator as far as the stone bridge leading towards the church of San Zaccaria where the perpetrator threw himself into the water. Robin then witnessed two unknown women take the man by the hand and pull him into a house.

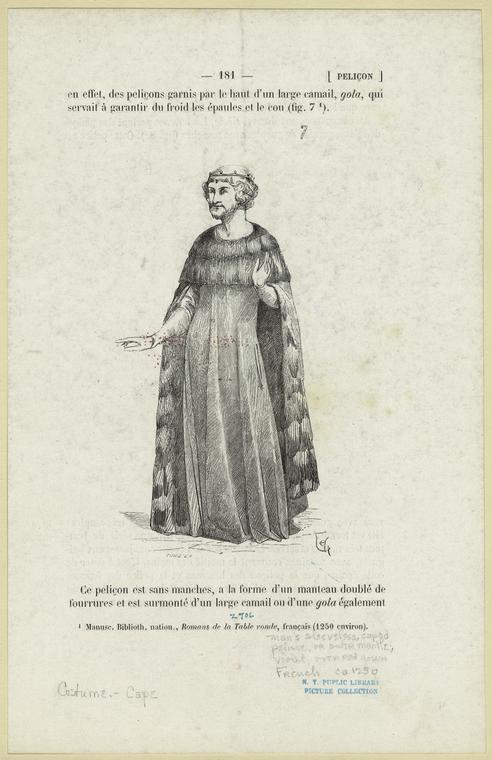

John lived through the assault. We know this because his interview with Triadano Griti, lord of the Signori di Notte (the night watch), survives. Since John did not know Latin, he was required to speak through a translator—in this case, his master, Henry Stromin. John gave a full account of the events, including a description of the perpetrator, “a young man with a black beard,” wearing a pelisse (a cloak with armholes) on his back. His fellow groom, Robin, gave an almost identical account of the events two days later, although John the Englishman acted as his interpreter at the time.

On the same day Robin was interviewed, the Signori di Notte’s investigation uncovered another witness: Thomas Furlano, flayer at the butchery of Rialto, a parishioner of San Marcuola, and a resident in the house of the Lady Magdalen Pagan. He testified that on 3 Mar. 1365, he was on his way to San Giovanni Nuovo (either the church or the square, both of which share the same name), when he heard the smacking of feet on the pavement behind him, causing him to turn. He spied one Mioranza the cap maker, running “as fast as he could with a pelisse on his back like a surcoat.” As he overtook him, Mioranza took off the pelisse and shoved it into Thomas’s hands, saying, “Take and keep this pelisse.” The witness did as he was told. He also noticed the Englishman (Robin) in pursuit, shouting “Run, rogue, as thou wilt, thou canst not escape, and shouldst swing.” There, at the water stair at the foot of the bridge leading towards San Zaccaria, the Englishman threw a punch at Morianza, who dodged it by jumping into the water. The witness then proceeded on his way and paid no more attention, although he did drop the pelisse off with a doublet maker he knew in the quarter of the Holy Apostles. The lord of the Signori di Notte asked him if he knew anything more about the man known only as Mioranza. Thomas replied that he did not know him by any other name, nor where he lived. Asked if Mioranza had a knife or any other weapon in his hand, Thomas replied not that he had seen.

Two days later, on 7 Mar. 1365, with the death of English John, the Signori di Notte were now conducting a murder investigation. Magister Bortolomeo of San Felice, a surgeon, went to check on the groom and discovered him dead. A careful examination of his body revealed a piercing of the skin on the left side, a layer of tissue (omentum) protruding from the wound and an effusion of blood. He confirmed that the stab wound was indeed the mortal wound and thus the cause of death.[6]

Unfortunately, the record comes to an end there, leaving the modern reader with many questions.

How could such a mundane exchange have led to a stabbing? Without scrutinizing the various elements of cultural conflict at play, it is hard to make sense of the interaction. There are two aspects worth singling out.

First, the Venetians believed the English were strangely obsessed with horses. With Venice’s narrow streets and canals, a horse was an unusual sight in the city. Venetians walked everywhere, and they did so with pride. As Filippo de Vivo has argued, for the Venetians, “Walking was a political and social statement.” It was a symbol of their egalitarian society: even the elite walked. But it was also an indication of their frugality. Why spend good money to ride a horse when you could use the legs God gave you?[7] The English insistence on bringing their horses on pilgrimage— a humble endeavor that one was supposed to complete both on foot and barefoot—was baffling to them. Even more perplexing was the waste of money and precious space in a densely packed city for stables dedicated exclusively to the care of horses.

Second, public urination was a serious nuisance in the Italian world. Street corners doubled as public toilets and the stench was legendary. When designing an ideal city, Leonardo da Vinci took the Italian penchant for public urination into account: all his buildings had round staircases so that there would be no dark corners to tempt people into public urination.[8] The man who stabbed English John surely saw that he was being polite by walking out back of the Inn to do his business; but John and Robin, who were accustomed to English stables and English stable etiquette, were astonished at anyone who would sully a stable in this fashion.

Was Mioranza ever caught? Unfortunately, I simply don’t know the answer to that question. If he was, he probably was not punished. English John’s stabbing would have been classified as a “murder of passion,” that is a killing “that seemingly exploded out of the tensions and conflicts of daily life in a hectic commercial city.” Guido Ruggiero tells us that only forty-nine percent of homicides of this nature were punished with death, the prescribed penalty.[9] More important still, it is unlikely that a Venetian judge would have sided with the English over his own countrymen based on the evidence of two foreign servants.

Did this unfortunate experience teach Henry Stromin and his retinue to become better guests while staying in a foreign country? One suspects that the next time a strange man peed in the stable next to Robin the groom, he probably did not speak up.

Notes:

[1] Ludvine-Julie Olard, “Venice-Babylon: Foreigners and Citizens in the Renaissance Period (14th-16th Centuries),” in Imagining Frontiers, Contesting Identities, ed. Steven J. Ellis and Lud’a Klusáková (Pisa University Press, 2007), 156.

[2] Laura Grazia Di Stefano, “How to be a Time Traveller: Exploring Venice with a Fifteenth-Century Pilgrimage Guide,” in Making the Medieval Relevant, ed. Chris Jones, Conor Kostick, and Klaus Oschema (De Gruyter, 2019), 174.

[3] Robert C. Davis, “Pilgrim-Tourism in Late Medieval Venice,” in Beyond Florence: The Contours of Medieval and Early Modern Italy, ed. Paula Findlen, Michelle M. Fontaine, and Duane J. Osheim (Stanford University Press, 2002), 120.

[4] Maria Fusaro, “Politics of Justice / Politics of Trade: Foreign Merchants in the Administration of Justice from the Records of Venice’s Guidici del Forestier,” Mélanges de l’École française de Rome. Italie et Méditerranée 126.1 (2014), para 13 and para 4.

[5] Jonathan Foyle, “Some Examples of External Colouration on English Brick Buildings, c. 1500–1650,” Bulletin du Centre de recherche du château de Versailles 1 (2007), para 21.

[6] Calendar of State Papers Relating to English Affairs in the Archives of Venice, vol. 6 (London, 1877), 1578-1580.

[7] Filippo de Vivo, “Walking in Sixteenth-Century Venice: Mobilizing the Early Modern City,” I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance 1 (2016), 132.

[8] Jane L. Stevens Crawshaw, Cleaning up Renaissance Italy: Environmental Ideals and Urban Practice in Genoa and Venice (Oxford University Press, 2023), 27.

[9] Guido Ruggiero, “Excusable Murder: Insanity and Reason in Early Renaissance Venice,” Journal of Social History 16.1 (1982), 115.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.