By Sara M. Butler, 27 November 2024.

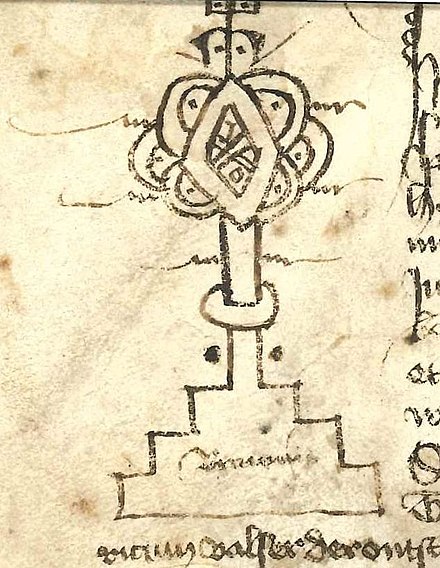

Unlike many other places in Europe, notaries public did not take hold and proliferate in England after the twelfth-century Legal Revolution. While judge-led law in the newly instituted inquisitorial system of justice implemented by the church and some Continental states necessitated a vast army of notaries to take down depositions and record court proceedings, in England, only the church courts saw the value in implementing this approach. In large part, the absence of notarial culture associated with England’s common law is why the records produced by the medieval courts are so pithy and unrevealing: an entire homicide case is described in a slender paragraph and the historian often must guess at the investigative process that took place behind the scenes. The same kind of case in a French or Italian court might well include a broad multitude of case materials, from witness depositions to the consilia of medical practitioners charged with determining cause of death. Without public notaries, England’s legal culture persisted in its orality long after other Europeans had realized the necessity of writing as proof in matters of possession or to document financial transactions. Michael Clanchy’s From Memory to Written Record: England 1066-1307 (1979)[1]emphasizes that it was all a matter of trust. The English were not prepared to see a written record as proof in and of itself. They clung to their orality, even as a fledgling culture of written documentation rose up around them. Thus, Anglo-Norman charters, for example, frequently had knives appended to them as symbols of conveyance: the English felt more comfortable with knives whose ownership was easily recognizable than with parchment, ink, and seals.[2]

What is surprising is just how long that orality persisted alongside written culture and the various ways the two interacted. An unusually well documented property dispute from the fifteenth-century English city of Calais that appears in the court of Chancery demonstrates that Englishmen and women continued to prize oral statements over the written record even at such a late date.

The case revolves around the last will and testament of Henry Meryfeld, a former burgess and alderman with substantial landholdings in the city of Calais and the surrounding area.[3] While Henry’s wishes were registered in the town book and also subject to an inquisition postmortem (because he held lands of the king in chief in his demesne), when it was time to put his wishes into action, officials discovered that the written record differed substantially from the collective memory of Henry’s friends and neighbors. The official record in the town book favored the family of Reginald Langham, Henry’s good friend and one of his executors, also the man who went on to marry Henry’s wife, Thomasine, rather than the family of John Pryket, Thomasine’s son by her first husband, who many claimed was Henry’s heir. Contentions surrounding this dispute came to a head many years after the death of Henry Meryfeld, and also after the deaths of both Langham and Pryket, with persuasive allegations of forgery abounding.

Many of Henry’s acquaintances were brought in to testify regarding his last will and testament. It is in these depositions that we see the authority of oral culture surrounding legal matters, apparent in the very language of the depositions. The witnesses repeatedly testified to the “common voice and fame” of the community. To underscore the Pryket family’s strong claim to those lands, Mayhewe Brave made clear that it was “the common voice and fame at all seasons and times,” while others stated simply that Henry’s wish for Pryket to inherit had been commonly known “at all times since” Henry’s death. Deponents were regularly described as men of “honest conversation,” dwelling and “conversant” in the town for years. Tensions over the will were referred to as “noise” and “much strange language and ‘aggrudging.’” Keen to explain how they knew what Henry wanted, deponents spoke of being at his deathbed and hearing this directly from Henry, who “openly said by mouth” in the last hour or two of his life what he wished; others stated specifically that his last will was “made by his mouth and not by writing.” The orality of the culture was acknowledged also in a letter written by John Wodehous, the city’s mayor at the time of the inquest, in which he recorded its findings. The letter was addressed to all those who “see or hear” it.

Several of those who testified had no personal knowledge of the situation, but still felt confident that John Pryket was the rightful heir because his claim was supported by the right people, reminding us that not all voices carried the same weight. James Grene declared that he “has no knowledge of this matter but only by report of diverse worshipful [that is, honorable] persons in Calais and by a common voice that has continued since his coming thither.” William Hamport was certain because he had heard it from his father many times. When Brother William George, from the White Friars at Calais, spoke up in support of Pryket, his words were described (in Latin no less!) as being “sacred words.”

During his lifetime, Henry Meryfeld also recognized the value of oral culture for protecting his interests. He had no intention of relying on a registration in the town’s book! Rather, he performed publicly his last wishes on a regular basis. When his stepson, John Pryket, was young, Meryfeld took him by the hand, and in front of a crowd of onlookers he led the boy down the street, pointing out to him the houses and tenements that would one day be a part of his inheritance, saying, “Lo, boy, all this shall by yours.” This act was not simply to reassure the boy that he would indeed be Henry’s heir after his eventual death. It was also for the benefit of the public, to impress on their minds what would be his last will and testament, in case he might someday need them to testify on his stepson’s behalf. Thomas Shipley told another version of this tale. When John Pryket came home from school, he would seek out his stepfather, who would say with great pride, “Lo, boy, see you this house? This shall be yours after the decease of me and your mother! Look yon, learn fast! I trust to God, you shall be mayor of Calais hereafter!” After Henry died and John’s mother, Thomasine, married Reginald Langham, the same kind of performances were staged by Langham. William Hamport reported that when Pryket and Langham walked down the street together, men would say, “Lo, yonder goes the father and son. Lo, Pryket shall have all the livelihood of Harry Meryfeld, which Langham has, after his decease and he shall be his heir also.”

The tavern was also a preferred venue for performances of this kind. John Crokey remembered Henry “diverse times in [the] tavern and other places and especially in his own tavern” (called “Le Steere,” on Laternstreet), he would have his stepson John with him, and he would say “Lo, this boy shall be my heir and have all my livelihood after the decease of his mother, my wife.” The tavern also figured largely for public remarks made many years later by John Pryket’s wife, Johanna, resentful because Langham, who stepped in to manage those properties during Pryket’s youth, simply would not relinquish them. In front of an audience of tavern-goers, including Richard Trewherman who later reported this conversation to the inquest, and also her father-in-law, Johanna derided her husband, “Sir, you have good will to talk and comment on other men’s matters, but you will not talk of the livelihood which your father Langham has and keeps from you.” To which, Langham would say, “What, daughter, after my decease he shall have it. Who shall have it else?” Surely, Johanna purposely staged those remarks, wanting to keep popular support for her husband’s claim to the lands alive in the public memory, no matter how long Langham lived.

Of course, the problem with oral culture is that our minds play tricks on us. Memory is a fickle thing. The allegations of forgery resulted in an inquest roughly thirty-seven years after the death of Henry Meryfeld. Accordingly, many of those who testified were old men. John Fox was fifty-six years old; John Fernour and Walter Fisher were sixty; John Goyne was sixty-four. Still others had since died, and their memories of the event were conveyed to the court by those who recalled relevant conversations. While most of the deponents were emphatic that Henry Meryfeld, on his deathbed as well as during his lifetime, chose John Pryket as his heir, the telling of his deathbed experience varies dramatically from one witness to the next. Steven Leycester was at Henry’s side when he died but had since passed away. Nonetheless, his account was conveyed by Brother William George. Apparently, Leycester saw William Orwell turn to Henry and ask him, “Henry, you be a sick man. How have you disposed [of] your goods? Who shall be your heir?” To which Henry replied, “John Pryket, my wife’s son, shall be my heir and have my livelihood after the decease of Thomasine, his mother.”

In the versions of the story told by John Scotte and John Spyve, Henry’s response was not quite so energetic. John Scotte, another alderman of Calais, explained that Henry was in such bad shape at the end of his life that he was “sitting in a chair not having any power or might to speak.” In fact, he had to designate his executors with hand signals: his wife instructed him, if “[John] Goldsmith, [Reginald] Langham, and I shall be your executors, hold up your hand.” John Spyve, who ostensibly also heard the story from Steven Leycester, reported that Henry was so sick with the palsy that when asked who his heir should be, it took everything he had to say, “Pryket, Pryket, Pryket.”

Henry’s behavior on his deathbed was not the only detail remembered differently by witnesses. Many of the witnesses spoke to the registering of the will in the town hall’s book during the time when Laurence Wotton was mayor of Calais. And yet, a group of deponents examining the record to determine whether it was indeed a forgery fixated on that detail, claiming that “Laurence Wotton was dead and buried the day and time when the said supposed device was entered and enrolled in the said common book of Calais and many days before the said entry.” The deponents remarked, it was “a thing to be impossible that any dead man should bear witness either record to any such enrolling and registering in that common book of Calais either unto any other book elsewhere!”

The surviving documentation include only the witnesses in support of the Pryket family’s claim. From their perspective, the written record was meaningless because it did not accord with what everyone living in Calais knew to be true from the vibrant memories of their interactions with Henry, sustained since his death by common voice and fame: Henry Meryfeld wanted his stepson, John Pryket, to be his heir. Seemingly, the commissioners agreed: although their final verdict is not recorded, the last folio in the file is an appeal by a disgruntled representative of the Langham family, hoping to have John Wodehous brought before Chancery to discuss the matter. As this case suggests, in fifteenth-century England, memories were more powerful than the written word.

[1] Michael T. Clanchy, From Memory to Written Record: England 1066-1307 (first edition, 1979; third edition, Wiley Blackwell, 2012).

[2] For example, Durham Cathedral’s archives have the broken knife of Stephen de Bulmer. As Michael Clanchy notes, “To its horn handle is attached a parchment label recording the details of the gift … which the knife symbolizes.” See Michael T. Clanchy, “‘Tenacious Letters’: Archives and Memory in the Middle Ages,” Archivaria 11 (1980/81), 117.

[3] The records in this case are drawn from The National Archives (Kew, Surrey), C[hancery] 1/26/39-51. To make this record more accessible, all quotations appear with modernized spelling, grammar, and punctuation.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

[…] Unlike many other places in Europe, notaries public did not take hold and proliferate in England after the twelfth-century Legal Revolution. While judge-led law in the newly instituted inquisitorial system of justice implemented by the church and some Continental states necessitated a vast army of notaries to take down depositions and record court proceedings, in England, only the church courts saw the value in implementing this approach. In large part, the absence of notarial culture associated with England’s common law is why the records produced by the medieval courts are so pithy and unrevealing … (more) […]

LikeLike