By Cassie Watson and Carolyn Strange; posted 23 September 2025.

The prosecution and sentencing of the Australian ‘Mushroom Murderer’ to life in prison for the poisoning of three relatives and the attempted murder of a fourth drew world-wide attention this year. Both the media and the trial judge described this murderer as unique — an outlier in the annals of crime whose “motive remains a mystery.” Yet, with the exception of the poison that Erin Patterson chose to use, the nature of her offence is entirely typical of the history of poisoning.[1]

Poison in the Pot?

Poisoning, a means of murder that requires no physical force or direct contact between perpetrator and victim, can be accomplished using natural products derived from plants, particularly alkaloids, but is more closely associated with mineral poisons like arsenic. There were few prosecutions for poisoning prior to the nineteenth century, but in an era of epidemic disease and short life expectancy it is possible that some unknown number of individuals got away with murder. The growing availability and wider range of poisons in the nineteenth century led to a noticeable rise in the number of prosecutions for poisoning crimes, between the late 1820s and the 1850s, aided by toxicologists who rose to the medico-scientific challenge of proving that a specific poison had caused illness or death.[2] Lethal substances like strychnine, cyanide, opium, phosphorus and arsenic were used in household products including wallpaper, cosmetics, medicines, insecticides and rodenticides — all of which could be adapted for criminal use.

The duties expected of wives and mothers, and demanded of servants, included food preparation and nursing the sick — domestic chores that allowed easy access to potential victims. By the mid-nineteenth century, a disproportionate number of persons prosecuted for attempted murder or murder by poison in Britain were women, and the majority were accused of using arsenic to poison intimates or members of the same household.[3] Arsenic, a tasteless and odourless compound, provided a means to kill over time, unlike faster-acting agents like strychnine, since it was easy to administer and difficult to distinguish from other common causes of death, including industrial exposure.[4] In recognition of its worrying role in suicide and homicide, the 1851 Arsenic Act placed, for the first time, legal restrictions on the sale of a poisonous substance. This legislation was however less effective than we might expect: Peter Bartrip has noted that “there is little reason to suppose that it exerted a significant influence upon the overall incidence of poisoning.”[5] Indeed, poisons remained disturbingly accessible to those who, like Graham Young in the 1960s and 70s, really wanted them; and no legislation could impose comprehensive controls on natural substances found in the wild. But of the poisoners that we know about, almost none used actual seeds, leaves or other plant materials, probably because they are difficult to disguise in food or drink.[6]

The Australian colony of Victoria attempted to follow the English precedent in 1857, with a bill to regulate the “safekeeping and sale of arsenic and other poisons,” but druggists and commercial producers resisted, demonstrating an enduring tension between those who profit from poisons and those seeking to prevent their misuse.[7] The preamble of the first statute to regulate poisons in Victoria, passed in 1876, stated what was widely acknowledged: “the unrestricted sale of Poisons often leads to accidents and the commission of crime.”[8] However, the act, and those that followed, did not regulate or prohibit the use of toxins found in nature, such as mushrooms.

Planning and Detection

The deliberation and deception noted by the judge who sentenced Erin Patterson earlier this month highlights a recurring theme in the history of poisoning, and distinguishes it from other weapons. Even fast-acting poisons can take hours or even days to produce death, depending on the dose and the victim’s health, and substances that take longer to produce illness and death, such as thallium, make planning possible, including the steps necessary to evade justice.[9] Its secrecy is the antithesis to a direct attack, and makes poison almost impossible to defend against. For this reason, many have categorised it as an aggravated form of homicide.[10]

The fact that poisoning may not initially be suspected is yet another unique feature of this method of killing, and so proof of a criminal offence has often rested upon circumstantial evidence. The nineteenth-century development of forensic toxicology brought more cases to light and led to more convictions, but reliable toxicological and pathological evidence concerning the cause of illness and death is not the first but the second stage in a successful prosecution. There must be some formal suspicion raised first, to lead to a medico-legal investigation. Criminals might try to evade prosecution through claims of accidental poisoning, or may not be detected at all if symptoms are misattributed to other conditions. In the Patterson case, prosecutors believe she made several attempts on the life of her estranged husband in the two years leading up to the murders for which she was convicted. Despite potentially serious ill effects, victims do not always suspect those close to them of deliberate poisoning.

Victim–Offender Relationships

Individuals who choose to use poison tend to target intimate partners, family members, employers, or neighbours.[11] This victim-offender profile indicates that poisoners have rarely posed a danger to the wider public, although authorities have often suspected convicted poisoners were guilty of multiple homicides. In such cases, prosecutors tended to focus on the charge that was most likely to result in conviction and, until the mid-twentieth century, execution. Notorious nineteenth-century examples include the multiple murderers Rebecca Smith (1849), William Palmer (1856), and Mary Ann Cotton (1873).[12] More recently, Harold Shipman proved to be exceptional in the worst possible way, as a serial predator who held a position of trust among victims otherwise unrelated to him.

In pursuit of convictions, prosecutors have followed a consistent script, fixing on the perpetrator’s exploitation of the victim’s (or victims’) trust and vulnerability to register the threat poisoners pose to social norms. But poisoning cases involving female perpetrators — servants, wives or lovers charged with the murder or attempted murder of employers, husbands or paramours, were deeply unsettling: they broke the law but also undermined social, cultural and economic hierarchies.[13] Male poisoners have also violated relationships of trust, although more often than women by exploiting positions of authority or power, such as that conferred by the profession of medicine.[14]

Unlike women, however, men’s crimes were not generally adjudged in terms of their gender. Regardless of the reality of their lives, female poisoners of the past were lambasted as unwomanly, devious, disagreeable, greedy, bad wives and mothers,[15] while male poisoners like Palmer and Shipman have been decried as cunningly sophisticated modern murderers, elevated above the common criminal by their medical knowledge and social status. Few of the fathers who poisoned their children, or husbands who poisoned their wives, garnered the same level of public scrutiny and censure as their female or medical counterparts. The media interest in the Patterson case, right down to the unflattering photos that are regularly republished, is essentially reproducing a narrative that crystallised almost two centuries ago.

Conclusion

John Trestrail suggests that it is possible that female poisoners are more successful at escaping detection, since, historically, the majority of detected poisoners have been male. As almost every toxic chemical can be identified, given an initial suspicion and some recognised parameters to guide an investigation,[16] we must reluctantly conclude that although few other mushroom murderers are known (Henri Girard in 1912 is the only one regularly noted),[17] it is not necessarily because they do not exist. Even in the absence of a known motive, then, it is clear that the Patterson case is both extraordinarily unique yet also fits neatly into historic patterns of murder by poison.

Carolyn Strangeis Professor of History at the Australian National University. She has published extensively on the history of gender, crime and justice. Her further thoughts on the Patterson case can be found at the ANU Reporter.

Images

Main image: Fredrick Accum, A Treatise on Adulterations of Food, and Culinary Poisons, 2nd edition (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1820), frontispiece.

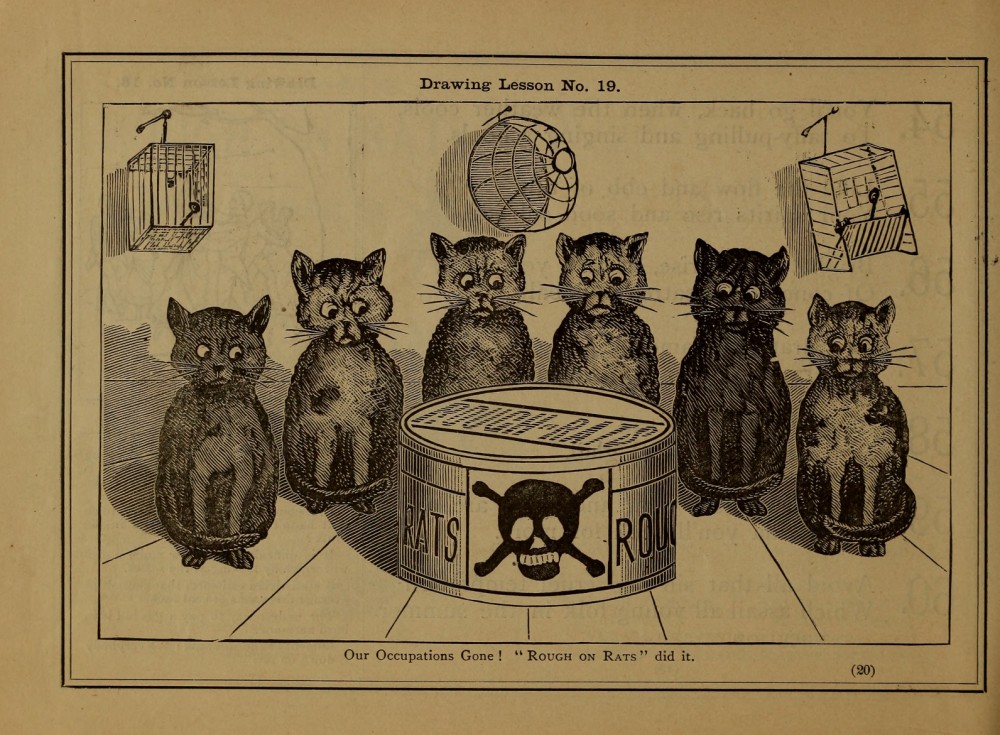

Victorian advertising trade card for rat poison, from the Rough on Rats company, printed in New York circa 1885. Free to use at Pinterest.

Death Cap (Amanita phalloides), Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria.

References

[1] See, in particular, John Emsley, The Elements of Murder: A History of Poison (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); Victoria M. Nagy, Nineteenth-Century Female Poisoners: Three English Women Who Used Arsenic to Kill (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015); Katherine Watson, Poisoned Lives: English Poisoners and their Victims (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2004).

[2] Katherine D. Watson, “Poisoning Crimes and Forensic Toxicology Since the 18th Century,” Academic Forensic Pathology 10 (2020): 37-39.

[3] Watson, Poisoned Lives, 46-47.

[4] James C. Whorton, The Arsenic Century: How Victorian Britain was Poisoned at Home, Work, and Play (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010); José Ramón Bertomeu-Sánchez, “Managing Uncertainty in the Academy and the Courtroom: Normal Arsenic and Nineteenth-Century Toxicology,” Isis 104, no. 2 (2013): 197-225.

[5] Peter Bartrip, “A ‘pennurth of arsenic for rat poison’: The Arsenic Act, 1851 and the Prevention of Secret Poisoning,” Medical History 36 (1992): 68.

[6] J. H. Trestrail, Criminal Poisoning, 2nd edition (Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, 2007), 30, 32-33.

[7] Terry Carney, “The History of Australian Drug Laws: Commercialism to Confusion,” Monash University Law Review 7, no. 1 (1980): 172-173.

[8] ‘An Act for regulating the Sale and Use of Poisons’, Victoria Government Gazette, 22 December 1876: 267-71, 267. Similar acts were passed elsewhere in the British Empire. See Shrimoy Roy Chaudhury, “Toxic Matters: Medical Jurisprudence and the Making of the Indian Poisons Act (1904),” Crime, History and Societies 22, no. 1 (2018): 81–105.

[9] When suspicion of homicide is aroused, evidence is sought to substantiate planning. Carolyn Strange and Les Hetherington, “Murderess or Miscarriage of Justice? A Case of Husband Poisoning in Early Federation New South Wales,” Australian Historical Studies 51, no. 3 (2020): 299-323.

[10] In Pennsylvania, for instance, lawmakers in 1794 specified poison and laying in wait as the two types of first-degree murder. Michael J. Zydney Mannheimer, “Not the Crime but the Cover-Up: A Deterrence-Based Rationale for the Premeditation-Deliberation Formula,” Indiana Law Journal 86, no. 3 (2011): 923-924.

[11] Emsley, Elements of Murder, 112-115; George Robb, “Circe in Crinoline: Domestic Poisonings in Victorian England,” Journal of Family History 22, no. 2 (1997): 176-190; Watson, Poisoned Lives, 47; Carolyn Strange, “The Female Poisoner’s Fate: Accounting for Lenient Outcomes in New South Wales, Australia, 1855-1955,” Crime, History and Societies 27, no. 1 (2023): 64. These patterns have appeared in other jurisdictions. See, for instance, Roddy Nilsson, “‘Arsenic the Size of a Pea’: Women and Poisoning in 19th-Century Sweden,” Scandinavian Journal of History 40, no. 1 (2015): 100.

[12] Watson, Poisoned Lives, 88, 101-104, 211-217.

[13] Mary S. Hartman, Victorian Murderesses: A True History of Thirteen Respectable English and French Women accused of Unspeakable Crimes (New York: Schocken Books, 1977); Kay Saunders, Deadly Australian Women: Stories of the Women Who Broke Society’s Greatest Taboo (Sydney: ABC Books, 2013). In some historical contexts, courts have deemed women incapable of carrying out such crimes. See Ebru Aykut, “Toxic Murder, Female Poisoners, and the Question of Agency at the Late Ottoman Law Courts, 1840-1908,” Journal of Women’s History 28, no. 3 (2016): 114–137.

[14] Watson, Poisoned Lives, 47.

[15] Nagy, Nineteenth-Century Female Poisoners, 162-167.

[16] Trestrail, Criminal Poisoning, 50.

[17] Ibid., 13. Girard is the only mushroom murderer included in Trestrail’s database of over 1000 historic cases.

Discover more from Legal History Miscellany

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.