Posted by Sara M. Butler, 19 May 2021.

On July 1, 2021, Ohio courts are entering into a new age of bail reform. Ohio’s Supreme Court ruled recently that not only must all Ohio counties adopt a uniform monetary bail schedule, but before resorting to cash bail, the courts must explore the option of release on non-monetary personal recognizance.[1] The motivation behind this extraordinary change is socioeconomic: it has long been recognized that the bail system privileges the rich. Those who cannot afford to cough up the cash for bail (or, at least the 10% required by a bail bondsman) are left to languish in prison until trial. This is true even of those accused of minor crimes, in which, if convicted, the maximum prison sentence would be less than the time it takes for the case to work its way through the judicial system to trial. Despite the inequity of the system, it has long endured because debt is such a powerful motivator. How else does one guarantee an indicted felon will appear for trial?

In an attempt to scandalize its readership into endorsing bail reform across the United States, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in February of 2020 published an opinion piece by Andrea Woods, staff attorney with the ACLU’s Criminal Law Reform Project, in which she provocatively describes bail as “ransom.”[2] Since reading it, I’ve been wondering whether the author realized that not only has the bail system always been unfairly slanted towards the affluent, but the system itself did indeed originate in hostageship. While Woods’ incendiary language was surely intended to shock and disgust, in making this unsavory comparison, she seems to have stumbled accidentally into the medieval history of bail.

Before King Henry II commanded the widespread construction of prisons across the English landscape, the courts relied chiefly on the model set by hostage-giving in warfare and diplomacy. Hostages functioned as the pledge to secure a treaty or a wartime commitment. Violation of the agreement endangered the hostage’s life.[3] When it comes to criminal indictments, hostageship was instead commuted to the promise of a monetary payment, technically the value of the individual in custody (his wergeld), as well as restitution to the injured party. In taking custody of the accused, a surety – either a family member of the accused or his feudal lord – assumed this financial responsibility if he failed in his duty to ensure the accused’s appearance at trial. The law defined the surety, also known as a pledge or a mainpernor, as a “living prison.”[4] Exactly what that entailed is unclear. Justices in the time of Edward III reportedly claimed it was entirely acceptable for the surety to imprison his ward.[5] Presumably he did whatever he needed in order to get the defendant to appear in court.

A surety’s financial burden became even more onerous after the Norman Conquest, when payments of the wergeld were phased out in favor of punitive fines with no set rates. In determining the sum due, royal justices seem to have been guided instead by a combination of factors: the defendant’s rank, the seriousness of the crime, and an ardent desire to deter flight. Amercements were suitably punitive. For example, in 1165, when the man Michael of Spikeswick pledged to have in court failed to turn up, he was fined a small fortune at 40 shillings (10 more shillings and the king could buy himself a new warhorse!).[6] In June of 1249, when Robert de Poluggeheney’s pledges failed to bring him to court armed and ready for trial by battle to defend his reputation from a charge of premeditated assault, justices fined them 60 shillings and one penny.[7]

The excessive nature of these fines meant that when an accused felon did jump bail, his beleaguered sureties were rarely able to pay the promised sums. Elsa de Haas tells us that normally the debt had to be paid in installments over a number of years.[8] If a surety could not pay the court’s penalty, he risked outlawry or even imprisonment (giving him plenty of incentive to keep a good eye on his ward until trial). Moreover, it was not just accused felons who were expected to produce pledges: if prosecution was initiated by appeal (that is, by private accusation), according to Bracton, both appellor and appellee were released to sureties on bail until trial.[9] Those present during a crime, as well as the first finder of the corpse were also required to find pledges. Thus, victims of crimes or their families, witnesses, and first finders all risked imprisonment if they could not find sufficient pledges to guarantee their presence at a future court appearance.

There are two key moments in the medieval history of bail. The Assize of Clarendon (1166) regularized the process of itinerant justice, that is the general eyre in which the king commissioned justices to visit each county on circuit to take indictments from a jury of presentment and to try cases of both a civil and a criminal nature. In doing so, the crown criminalized some private offenses (such as homicide) and demanded that felonies be adjudicated by royal rather than local officials. At the same time, the crown loosened the requirements for indictment, permitting juries of presentment to accuse upon suspicion alone. Because of the extended period between eyres, bail became utterly critical: otherwise, a suspected felon, whose accusation rested on rumor alone, might sit in prison awaiting trial for anywhere between four and twelve years.[10]

Responding to popular concerns that not all accused felons should be permitted to roam freely, chapter 15 of the Statute of Westminster I (1275) proffers a list of all those who do not merit bail. The preamble states that prior to this, the only persons deemed non-replevisable were:

- those accused of homicide,

- those arrested upon command of the king, and

- those suspected of forest offenses.

The statute adds to this list:

- those who had previously been outlawed,

- those who had abjured the realm,

- approvers,

- those taken with the mainour (i.e. with stolen goods in their possession),

- thieves openly defamed,

- those appealed by approvers (providing the approver was still alive and the person he appealed was not of good name),

- arsonists,

- counterfeiters of the king’s seal or monies,

- excommunicates, and

- those accused of “treason, touching the king himself.”[11]

The legal treatises of the age provide a number of additional categories of non-bailable suspects. According to Bracton,

- if a person misses the first three exactions (summons to hear his indictment), then finally shows up for the fourth exaction, he loses the right to bail.[12]

Britton includes also:

- alleged rapists,

- those who have carried off nuns from their convents, and

- ravishers of wards whose marriages belong to others.[13]

Everyone else was automatically bailed – providing, they were capable of finding sureties to guarantee their appearance at trial. Given the excessive nature of the fines, it is not surprising that many individuals accused of felonies could not. Those who were poor or of dubious reputation, in particular, were unlikely to find men willing to stake their purses and reputations on a court appearance. Imprisonment alongside suspected murderers, traitors, and ravishers of nuns was their inevitable fate.

Of course, even for those imprisoned on crimes that were purportedly non-replevisable, bail was not really off limits to those who had money. The Close Rolls are filled with hundreds of individuals accused of crimes that were supposedly non-bailable and yet they somehow wangled bail “in compliance with the King’s pleasure.”[14] A glance at the Pipe Rolls resolves the mystery of what exactly might prompt the king to alter his legal stance so dramatically and endanger the lives of his subjects: a hefty fee. In the year 1241-42, Beatrice daughter of William paid half a mark (6s. 8d.) to be released from York’s prison; Robert Stawic, presumably a man of greater means, paid 20 shillings for the same privilege.[15]

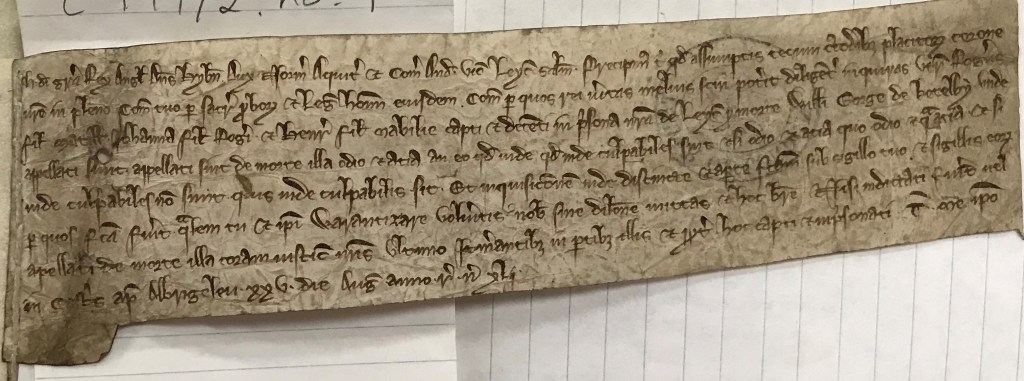

Those who believed they were imprisoned unjustly had one more card to play: they could argue that they were not guilty of the alleged crime, but had been accused purely out of hate and spite. Granted, this maneuver also required the ready availability of money to purchase the writ de odio et atia (also known as a “writ of inquisition) necessary to initiate an inquest into the allegations.[16] A successful inquest would see the defendant home on bail until trial. Once again, there was no standard fee for this writ. Elsa de Haas notes that most commonly, prisoners paid one mark or half a mark, however, the price might range all the way up to one hundred shillings and more.[17] At the 1241 Oxfordshire eyre, Peter of Leigh paid a full £10 for an inquest when he stood accused of killing Erneis del Frith and stealing 18 cartloads of Erneis’ grain. The jury’s verdict, that he was not guilty of the homicide, but that he had taken the grain after Erneis died, at the very least, earned him bail until his trial proper.[18]

Many of those who paid for an inquest de odio et atia probably never should have been imprisoned in the first place. Jurors frequently found that the homicide was the result of self-defense. At the July 1245 inquest into the allegations against William Kyng, accused of having killed Ralph de La Grave at Nottingham, jurors reported that he had done so “not out of felony nor by malice aforethought.” Around the hour of vespers, Ralph assaulted William, saying that he wished to kill him. William was convinced that death was imminent, and so with a lance in his hand, he defended himself. His plan was to hold Ralph off with the lance, however, Ralph turned quickly, not seeing the lance he ran upon it so that the lance pierced his chest and he died “by accident.”[19] Self-defense fell into the category of excusable homicide – by the end of the thirteenth century, the process had changed so that when an indicting jury raised these circumstances, instead of prison, William’s case would have warranted a pardon de cursu.

Others alleged that the “homicides” for which they stood accused were, in fact, deaths by misadventure. Jurors at the December 1245 inquest de odio et atia sponsored by Thomas le Provost, William Market, Ralph le Hopere, Silvester de Cruce, and Ralph de Biesteton, imprisoned at Winchester, found that none of the men were in fact guilty of the homicide of William Welifeld. Indeed, the jury declared that William had fallen into a well filled with water and drowned accidentally, only for his mother, Matilda, to appeal the five men out of hate and spite, presumably for some past injustice. [20]

Sometimes jurors blamed malicious accusations of homicide on long-running disputes over land, an unpaid debt, or revenge for a humiliating physical altercation after a night of too much drinking. At the very least, the majority of those individuals found freedom until trial through the inquest de odio et atia.

But what of those who couldn’t afford the writ to initiate this process? How many others sat in prison on false accusations for years on end simply because they were poor? Indeed, with the exorbitant rates charged by chancery for the writ de odio et atia, one might be fairly comfortable and still incapable of amassing such a large sum of cash. This may well explain why Ralph de Rouceby remained in prison for eight years before he was able to pay the 40 shillings necessary for bail until trial.[21]

The injustice of imprisonment until trial simply because of one’s poverty is what originally prompted those rebellious thirteenth-century barons to include clause 36 in the Magna Carta: “Nothing is to be given or taken in future for a writ for an inquest concerning life or members, but it is to be given without payment and not denied.”[22] And yet, somehow, this leveling clause was never implemented in medieval England.

Given all the humanitarian reforms that have taken place in the Anglo-American legal system since then, it is a wonder that the bail system has survived well into the twenty-first century not only intact, but with great elaboration: the medieval world would have approved of professional bondsman and bounty hunters. By prioritizing non-monetary personal recognizance, Ohio may be taking its first step beyond the Middle Ages.

Images:

Apostle Peter released from Prison. Jacopo di Cione (1370-71), Philadelphia Museum of Art. Public Domain. Wikipedia.

Writ de odio et atia. The National Archives, C 144/2, no. 1. Courtesy of The National Archives, Kew, Surrey. Photo credit: Sara Butler.

[1] Laura Hancock, “Ohio Supreme Court approves rule changes expanding bail reform,” cleveland.com, 30 Mar. 2021, https://www.cleveland.com/open/2021/03/ohio-supreme-court-approves-rule-changes-expanding-bail-reform.html.

[2] Andrea Woods, “Using Bail as Ransom Violates the Core Tenets of Pretrial Justice,” News and Commentary, ACLU, 5 Feb. 2020, https://www.aclu.org/news/smart-justice/using-bail-as-ransom-violates-the-core-tenets-of-pretrial-justice/.

[3] Although as Adam Kosto tells us, in fact, hostages were rarely executed in retaliation. Adam J. Kosto, Hostages in the Middle Ages (Oxford, 2012).

[4] William De Gruchy, ed., L’Ancienne Coutume de Normandie (Jersey, 1881), ch. lxviii.

[5] Nicholas Statham, Abridgment of Cases (1490), The Ames Foundation, Harvard University, “mainprise”, 11.

[6] Melville Bigelow, ed., Placita Anglo-Normannica: Law Cases from William I to Richard I preserved in Historical Records (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1879), 270; Frances Gies, The Knight in History (New York, 1984), 30.

[7] C.A.F. Meekings, ed., Crown Pleas of the Wiltshire Eyre of 1249 (Devizes, 1961), 206-7.

[8] Elsa de Haas, “Concepts of the Nature of Bail in English and American Criminal Law,” The University of Toronto Law Journal 6.2 (1946), 391-2.

[10] Caroline Burt, “The Demise of the General Eyre in the Reign of Edward I,” English Historical Review 485.120 (2005), 3.

[11] 1 Statute of Westminster, 3 Edw I (1275), Statutes of the Realm, vol. 1, 30.

[13] Britton, Francis Morgan Nichols, I, 182 and 183.

[14] George Hall, ed. The Treatise on the Laws and Customs of the Realm of England Commonly called Glanvill (Oxford, 1993), 177.

[15] Henry Lewin Cannon, ed., The Great Roll of the Pipe for the Twenty-Sixth Year of the Reign of King Henry III, A.D. 1241-1242 (New Haven, 1918), 38.

[16] Note: paying for a writ de odio et atya was different than pleading an exception de odio et atia. Susanne Jenks explains the difference. See her, “The Writ and the Exception de odio et atia,” Journal of Legal History 23.1 (2002): 1-22.

[17] Elsa de Haas, Antiquities of Bail: Origin and Historical Development in Criminal Cases to the Year 1275 (New York, 1966), 106.

[18] Janet Cooper, ed., The Oxfordshire Eyre 1241 (Oxfordshire Record Society, vol. 56, 1989), p. 134, #884.

[19] The National Archives (Kew, Surrey) C 144/1, no. 1.

[20] Calendar of Close Rolls, Henry III, vol. 5 (1242-1247), 373-381.

[21] Noted in the Rotuli hundredorum by Elsa de Haas, Antiquities of Bail, 92.